stpete-hero-min

Women’s Work: A Survey of Female Photographers

On view at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, April 16 – September 11, 2022

Women have played vital and sustained roles in the making and advancement of photography since its invention, more so than in any other visual medium. Unfortunately, this contribution has often been overshadowed by a myopic focus on photography by men throughout the medium’s history. For every Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) or Diane Arbus (1923–1971), scores of other accomplished, talented women photographers lost to the historical canon due to constricting gender-specific issues like child-rearing responsibilities, lack of societal acceptance, or inadequate financial support. This exhibition features work by well- and lesser-known photographers—drawn from the MFA’s permanent collection—who have persevered and helped push the photographic field forward.

Diane Arbus, Girl in a Shiny Dress, New York, 1967, Gelatin silver print,

Museum purchase with funds provided by William and Carol A. Upham

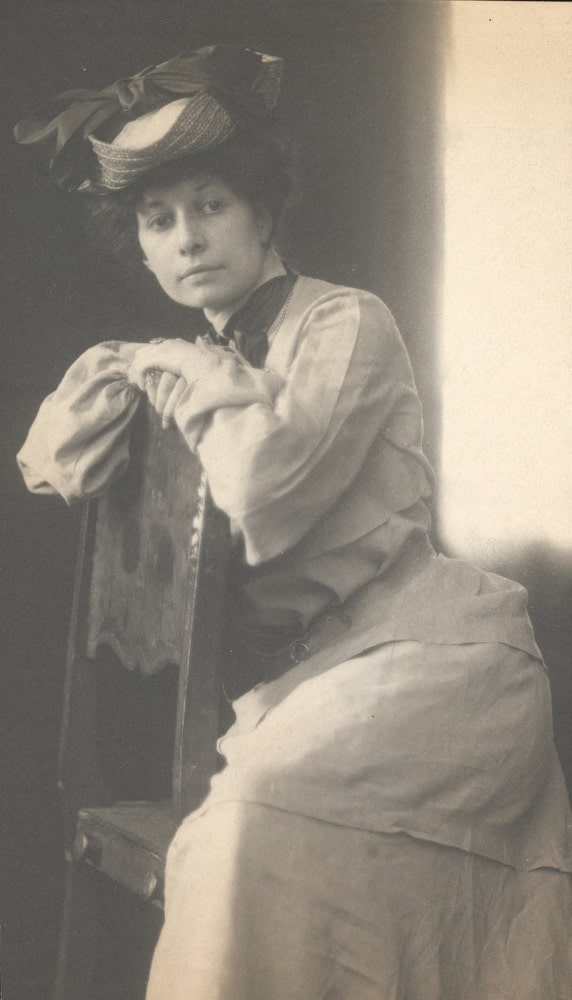

One of the earliest and most recognized women photographers was Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879), who started photographing at 48. Cameron’s soft focus style and acceptance of process imperfections gave a timeless quality to her portraits of notable men and women, considered among the first examples of fine art photography. Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934) also began her photography career after her children were grown. She was a principal member of Alfred Stieglitz’s (1864–1946) Photo-Secession group of pictorialist photographers; he highly regarded her as “beyond dispute, the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day.” Her portraits of women, family, and religious narratives were well within the standards of appropriate subject matter for women photographers and emphasized the innocence of children, safeguarded from the world’s ills. But Käsebier was also committed to supporting the continued presence of women in the field. Her willingness to act as a mentor helped normalize women’s roles as leading portraitists—Alice Boughton (1866–1943), Jane Reece (1868–1961), and Helen Lohmann (active in The 1910s)—all benefited from her guidance. Beyond portraiture, she inspired a generation of art photographers working in the pictorialist style. These included Laura Gilpin (1891–1979), who captured the beauty of the West, while Doris Ulmann (1882–1934) documented waning traditional cultures in rural communities.

- Julia Margaret Cameron — Blessing and Blessed

- Gertrude Käsebier, American, 1852–1934, Happy Days, 1902, Platinum print, Gift of Miss Mina Turner, Artist’s granddaughter

As the social tensions that caused World War II (1939–1945) moved inexorably forward during the 1920s through 1930s, women’s participation in photography expanded considerably. The work of leading avant-garde photographers like Germaine Krull (1897–1985) and Ilse Bing (1899–1998) reflected a new modernist vision: unusual vantage points, off-kilter cropping, and a focus on industrial, modern subject matter. This new vision included active experimentation in photography through photograms, reflection, and dramatic lighting, as seen in the work of Lotte Jacobi (1896–1990) and Carlotta Corpron (1901–1988). On the West Coast, photographers associated with Group f/64 embraced the camera’s unique mechanical qualities by creating detailed close-ups with astonishing clarity. Imogen Cunningham’s (1883–1976) sharply focused images of flowers were particularly revered. In New York City, the Photo League—an organization devoted to the photographic exploration of social complexities—boasted a membership that was at least a third female. Longtime Photo League member Berenice Abbott (1898–1991), fascinated with the city itself, spent years documenting its sometimes awkward transition into a modern metropolis.

- Ilse Bing, American, b. Germany, 1899–1998, Chairs, Champs-Elysees, Paris, 1931, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Terry P. Loebel Family

- Imogen Cunningham, Water Hyacinth 2, c. 1925, Gelatin silver print, NEA & FACF photography purchase grant

As documentarians, women used photography to influence public policy and highlight social concern areas. Around 1900, Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864–1952) photographed African American students at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute. Almost forty years later, Farm Security Administration photographers Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) and Marion Post Wolcott (1910–1990) documented the poverty-stricken South after the Great Depression. Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971) broke many gender-based restrictions; she was hired as one of Life magazine’s first four salaried staff photographers and the first woman photojournalist to fly combat missions with the military during World War II.

- Marion Post Wolcott, American, 1910–1990, Picnic on Running Board, 1941, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Dr. John Schloder in honor of Terence S. Leet and the Museum’s 50th Anniversary

- Margaret Bourke-White, American, 1904–1971, Self-Portrait, 1931, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Ludmila and Bruce Dandrew from The Ludmila Dandrew and Chitranee Drapkin Collection

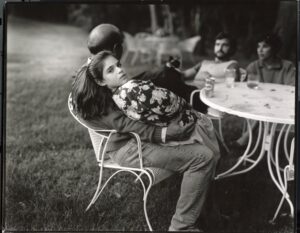

Women photographers were also interested in reclaiming the female body from the ever-present male gaze. Ruth Bernhard (1905–2006) embarked on a series of female nudes to offer a counter-narrative to the objectification of women. Barbara Morgan (1900–1992), enamored with modern dance, created a series focused on the movement of the female body. Feminist philosophy fueled new interpretations of body image and gender politics. Judy Dater’s (b. 1941) deeply psychological portraits of female nudes are collaborative efforts inaccessible to a male photographer. Conversely, Sam Contis (b. 1982) explores the connection between the Western landscape and the male body. Not surprisingly, the 1960s provided women with fertile ground for the dissolution of established norms. With interest in piercing society’s rigid substrata, Diane Arbus’s (1923–1971) photographs of both the hyper-accepted (the rich and famous), as well as societal outliers altered the perception of “acceptable” subject matter.

- Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Portrait of a Young Woman, 1900, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Ludmila and Bruce Dandrew from The Ludmila Dandrew and Chitranee Drapkin Collection

- Torso Ekstasis by Barbara Morgan

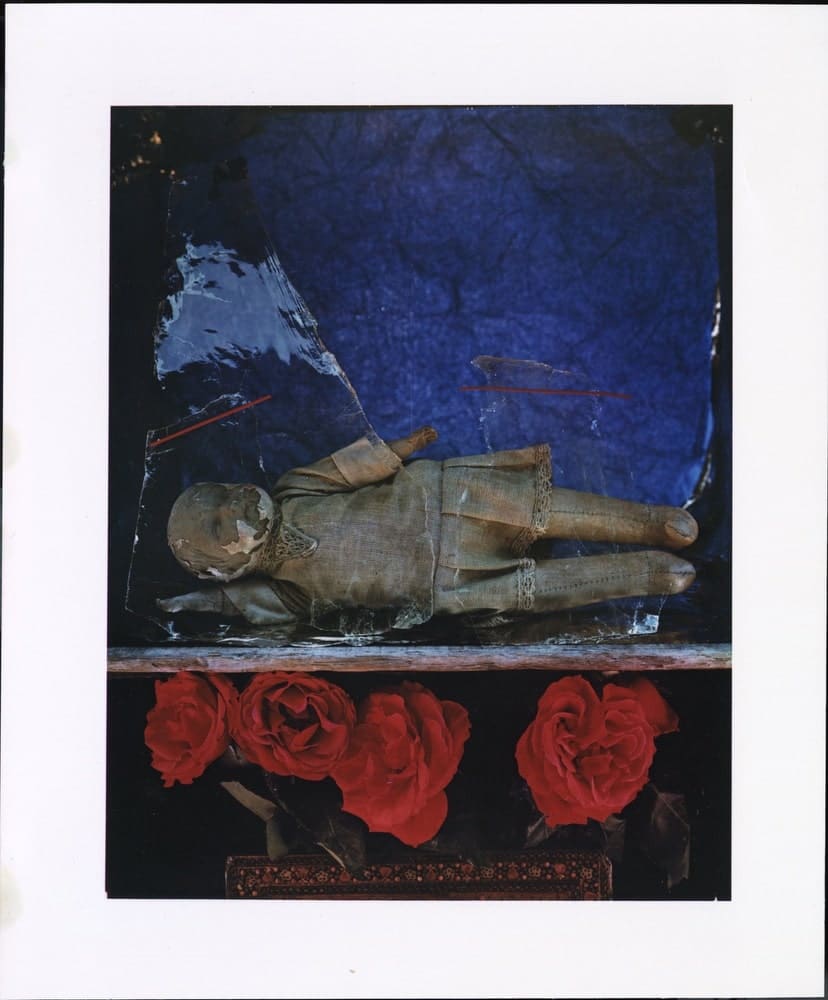

In the latter part of the twentieth- century (and into the twenty-first), women utilized the photographic medium to highlight issues of personal importance. Some draw attention to societal shortcomings: Deborah Luster (b. 1951) considered the dehumanizing nature of the prison system; Mary Ellen Mark (1940–2015) addressed the rise of immigration in Australia, and Fiona Foley (b. 1964) documented the stereotypes of her indigenous Australian community. Others use photography more intuitively: Mariana Yampolsky (1925–2002) and Graciela Iturbide (b. 1942) explored the seemingly magical aspects of Mexican culture, while Olivia Parker (b. 1941) and Jo Whaley (b. 1953) reinterpreted the traditional still life in surreal and playful ways. Landscape photography—once considered the almost exclusive purview of male photographers—provides another vehicle for personal exploration. Photographs by Marion Patterson (b. 1933) and Mary Randlett (1924–2019) convey the incredible beauty of nature, while work by Paula Chamlee (b. 1944) and Fay Godwin (1931–2005) connect more intimately to home. Linda Connor’s (b. 1944) work invites the viewer to a transcendental spiritual connection.

- Olivia Parker — The Eastern Garden

- Marina Yampolsky, American, 1925–2002, Petalos, 1980, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase with funds donated by an anonymous donor

- Jo Whaley — Mourning Dove, Winter

Women photographers will probably always be inextricably linked to the subject of children. But instead of emphasizing the idyllic innocence like their nineteenth-century predecessors, photographers like Sally Mann (b. 1951) look at the complicated internal world of preteen girls. Andrea Modica (b. 1960) depicts children struggling with the adult pressures of poverty and obesity, and Catherine Wagner (b. 1953) explores learning environments and the unrelenting pressure to excel.

Although women were involved with photography for as long as their male counterparts, surprisingly, few have taken their rightful place in photographic history. With a broad interest growing in museums across the country to expand the canon to be more inclusive and reflective

of under-recognized contributors, this exhibition seeks to reaffirm the contributions of known women photographers and to open the door to the possibility of discovering others.

- Dr. Jane Aspinwall — Curator of Photography at the MFA St. Pete

To learn more, visit: https://mfastpete.org/

Share This Story!

CATEGORIES

RECENT POSTS

NEWSLETTER

Sign up to receive exclusive content updates

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE