Welcome to Morocco

Friends, Fantasy, and Fatigue in North Africa

By Mike Ragsdale | Photography by Caty Dansan

The taxi driver sat on the curb beside me and lit a cigarette. He offered me one, but I politely declined in a language he didn’t understand. It was well after midnight and the sweltering heat of the day had settled to a more tolerable temperature. Despite the late hour in this residential neighborhood, distant sounds of revelry ricocheted through an alley across the street.

“At least someone is having fun,” I sighed.

“It is a wedding,” said Badr, who helped guide us by foot through the bewildering maze of dark, narrow corridors of the medina in the moments after the accident. “It will last for three days. The first night is for the bride, the second night is for the groom, and the final night is for the entire family.”

The glass doors on the building behind us swished open, and a young man in green scrubs emerged from the dimly lit reception area.

“Your friend—he go into surgery now,” he said in broken English. “I let you know when it is over.”

“Welcome to Morocco,” I thought.

Working out can be tough, painful, and unpleasant. It can make you light-headed and nauseous. It’s “working out,” after all, not “playing out” or “lounging about,” which is more my speed. And yet, despite all the suffering and pain and dread, the physically devout faithfully line up behind torture machines every morning, literally tearing their muscles apart so those tissues will heal back thicker, denser, and stronger than the day before. Though this process is excruciating, it’s also exhilarating. After you’re done, you feel a proud sense of accomplishment, I’m told. And the lifelong rewards are obvious.

International travel is a lot like that. Many times, you find yourself in strange places, asking yourself questions like: Why in the hell am I here? Why didn’t I just stay at home where everything is familiar, easy, and comfortable? What did I just step in? What is that man pulling out of his ear?

Sitting on a curb after midnight outside a Moroccan emergency room and waiting for news of my friend was one of those times.

Even seasoned travelers experience a little culture shock when they first enter a third-world country. My wife, Angela, and I have explored some fairly challenging places, including Myanmar (Burma), Transnistria, Rajasthan in northern India, Moldova, Cambodia, and Bosnia, to name a few. Each presented its own cultural collisions.

This time was a little different, though, because we weren’t traveling alone—we were with a group of ten wonderful friends, mostly from our hometown of Santa Rosa Beach, Florida. While a few of us were veteran travelers, some of us had never ventured far outside the United States, except to all-inclusive-style resorts in Mexico or the Caribbean, where the most awful thing likely to happen to you is a bad sunburn or a cheap rum hangover.

In the months before our journey, we tried our best to avoid overromanticizing travel to a country like Morocco. And yet our group’s countless pretrip conversations could not help but be sidetracked by seductive visions of ancient streets lined with exotic merchants, slow camel rides across windswept dunes, and decadent tagine dinners at lantern-lit tables.

International travel is a bit like working out. I say this with absolutely no fitness experience whatsoever, but I asked my wife, and she confirms there is some truth to my theory.

On a workout difficulty scale from one to ten, Morocco probably scores a six. An all-inclusive Caribbean-style resort would rank a one. It’s easy exercise. Most Western European countries are twos. Eastern European counties would score threes or fours, as would some Central American destinations, like Costa Rica. Places like Thailand and Bali are fives, if only because of the stark cultural differences. Almost anyone can venture to any of those places and enjoy a good time with relatively little discomfort or disorientation.

Places like Ecuador, Cambodia, and Morocco rank a little higher. They’re truly fantastic places to visit—the people, food, sights, and experiences are all unique and worthwhile. But some places can also be a little more intimidating for outsiders. There’s a slight undercurrent of tension, often fueled by a testosterone-high hierarchy found in some societies. You might get scammed in Asia or India, but I don’t ever remember being worried about getting my ass beat. The thought of physical violence just never occurs to you because random violence just isn’t part of the local culture. But that thought does sometimes occur to you in places like Quito and Marrakech, where cold stares from tourist-fatigued locals can begin to mess with your mind.

Myanmar and northern India score a seven or eight. They’re extremely friendly—just harder for travelers to navigate due to lack of any familiar infrastructure. I have yet to experience a nine or a ten. I suspect that very remote African villages or mission trips deep into impoverished communities would rank nines. The highest score of ten is reserved for the most dangerous and inaccessible places on Earth, such as ascending Mount Everest, providing triage relief immediately after a major disaster, or conducting a midnight raid in Syria. I leave those sorts of adventures to the heroes and saints among us.

So, for someone who has never spent much time outside of the United States, jumping straight into a third-world country is a bit like going from power walking around a high school gymnasium to a P90X fitness routine. It can be mentally and physically overwhelming.

Upon arrival in Morocco—exhausted from thirty hours of travel—our airport shuttles unceremoniously dumped us at the edge of Marrakech’s city wall. Our riad (basically Morocco’s version of a bed and breakfast) was inside the walls of the medina (old city), where centuries-old gates and narrow corridors prevent intrusion by car.

“We walk from here,” I said, quoting Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom—which no one noticed.

I could see nervous anxiety on the weary faces of our group. Two donkeys were tethered by our gate, standing next to piles of their own waste. A flaming heap of rubbish burned nearby. Motor scooters zipped in and out of the tiny door like hornets darting to and from their hive.

Handsome young Badr was there to greet us.

We walked in a tight cluster for ten minutes or so, dragging our roller luggage through alleys and tunnels, dodging motorcycles, murky puddles, and stoic stares from veiled faces. “How in the hell will we ever find this place on our own?” I worried.

Welcome to Morocco,” he said with a genuine smile and a warm handshake for each of us. “Please, follow me.

After such sleep-deprived sensory overload, our riad (Riad Porte Royale) felt like a scintillating sanctuary. We enthusiastically dispersed throughout the gorgeous three-level, five-bedroom courtyard home to explore and claim our bedrooms. Badr and a woman presented us with freshly squeezed juice. We gathered around the large outdoor dining table beside the splash pool and toasted one another. “To Morocco!” we cheered, even though I could tell that a couple of us were secretly calculating change-of-ticket costs for early flights out.

Rather than succumb to the slumber that all of us desperately craved, we decided to power our way into the evening in an attempt to get our bodies and minds on local time. As the sun began to cast long shadows across the African rooftops, we mustered up our collective courage and, with a telltale tourist map firmly in hand, we marched our way back into the chaotic maze. It took a while—and some good fortune—but we eventually discovered a wonderful restaurant deep in the medina, serving fine wine, authentic tagine, live music, and enough laughter to finally set our rattled minds at ease.

At midnight, we found ourselves still very much awake, enjoying cocktails in our courtyard and on the riad’s rooftop. As I sat in a lounger and stared up at the star-filled Moroccan sky, I breathed a sigh of relief. “We’re going to be alright,” I thought.

Then I heard a cascading series of crashes that seemed to go on forever, shattering the peace and silence of the night. What in the hell was that?

I darted downstairs to discover shattered glass on the steps and floor, everywhere. Standing there—shirtless and with a stunned look on his face—was our friend Kevin, holding his right hand aloft, blood pouring down his arm.

Kevin had slipped on the slick, stone stairs. As he tumbled down, he instinctively extended his right hand to help break his fall. His hand went straight through a large light fixture on the wall, shattering the untempered glass and gashing a deep, gaping wound in his palm.

Fortunately, two of our traveling companions, Kasie and Bridgette, are nurses, so they instinctively jumped into action. They laid Kevin down on the bed and applied pressure to the wound. They picked shards of glass from his hand, comforting him as they worked with makeshift tools.

“He’s losing a lot of blood,” whispered Bridgette. “I think he might have cut an artery.”

“We’re not going to be able to stop the bleeding,” said Kasie after a few more minutes of concentrated effort. “We need to get him to a hospital.”

With his hand bandaged but still bleeding, Badr led Kevin and me back through the dark maze toward the medina’s exterior wall.

“We can find a taxi there,” said Badr.

My experience is that unless you’re in a combat zone, the real risk in visiting foreign countries isn’t terrorists. Or being imprisoned. Or getting mugged. Frankly, it’s getting hurt out in the middle of nowhere and finding yourself hours away from proper medical help. It’s falling off a temple in Bagan and breaking your spine. It’s getting into a car wreck at a random intersection, four hours deep in India’s Khuri desert. It’s as simple and fast as falling down some stairs and cutting an artery. These are the most dangerous moments because the emergency services that we all have come to expect sometimes aren’t available.

Fortunately, our new friend Badr got us the help we desperately needed that night, delivering us to the best hospital and then translating for us with doctors, nurses, and specialists. Kevin underwent emergency surgery. The bleeding was stopped, and the severed tendon was repaired. Disaster averted.

However, because of the anesthesia, the hospital staff wouldn’t let me take Kevin back to our riad that night. As he lay there disoriented in the recovery room, I assured him that I would in fact return to get him in the morning.

“Welcome to Morocco,” I smiled.

Even though his fingers were visibly black and blue outside the bandages, Kevin never complained about his injury during the remainder of our trip—not once. Locals asked if he was a prizefighter.

After a couple of days, our culture shock began to subside, as it always does. We found ourselves relishing all of the beauty and romanticism that Marrakech has to offer. We usually slept in late and indulged in the royal spread of breakfast delights that the riad staff prepared fresh for us each morning. Angela sometimes led a rooftop yoga class for anyone not too hungover to participate. By day, we meandered through the alleys of the souk (marketplace), exploring exotic shops, interacting with colorful characters, and finding refuge from the ground-level chaos in rooftop restaurants. We ventured through the central plaza once or twice, where cobras, vipers, camels, monkeys, and touts tirelessly hustled the passing crowd.

We skipped most of the traditional tourist destinations, instead favoring the authentic buzz of life on the streets.

“Would you like to go to a museum?” asked Badr during one of our strolls.

“As far as I’m concerned, this whole place is a museum,” replied Trevor. I couldn’t have agreed more. The bustling streets of the medina are living history.

Our excursion to the Ourika Valley to the southeast was also a highlight. We explored colorful Berber villages built into the hillsides, took rocky hikes to hidden waterfalls, and dined in riverbed restaurants where plastic chairs and tables were set up right in the lazy water.

That’s how we spent our days. But the nights—well, that’s when our group showed its true colors.

I’ve learned when traveling in difficult places, you sometimes need to “reward” yourself after an exhaustive day of haggling and mishaps. We rewarded ourselves a lot in Marrakech, indulging in upscale restaurants, such as Jad Mahal and Lotus Club, and later partaking in cocktails and dancing until the late hours in swanky lounges like Silver, Nikki Beach, and 555, where the action doesn’t even start until two. Get there before that and it will just be you and the Russian hookers, with each of you sitting around waiting for better prospects.

After the frenzy of Marrakech, the city of Fez in the north was a delightful surprise. Although both cities are home to roughly a million people, Fez still felt like a small town: genuinely warm and welcoming. As you strolled along, eager merchants would invite you into their shops, but if you declined they would simply and sincerely respond, “No problem, my friend. Welcome to Fez.”

We explored colorful Berber villages built into the hillsides, took rocky hikes to hidden waterfalls, and dined in riverbed restaurants where plastic chairs and tables were set up right in the lazy water.

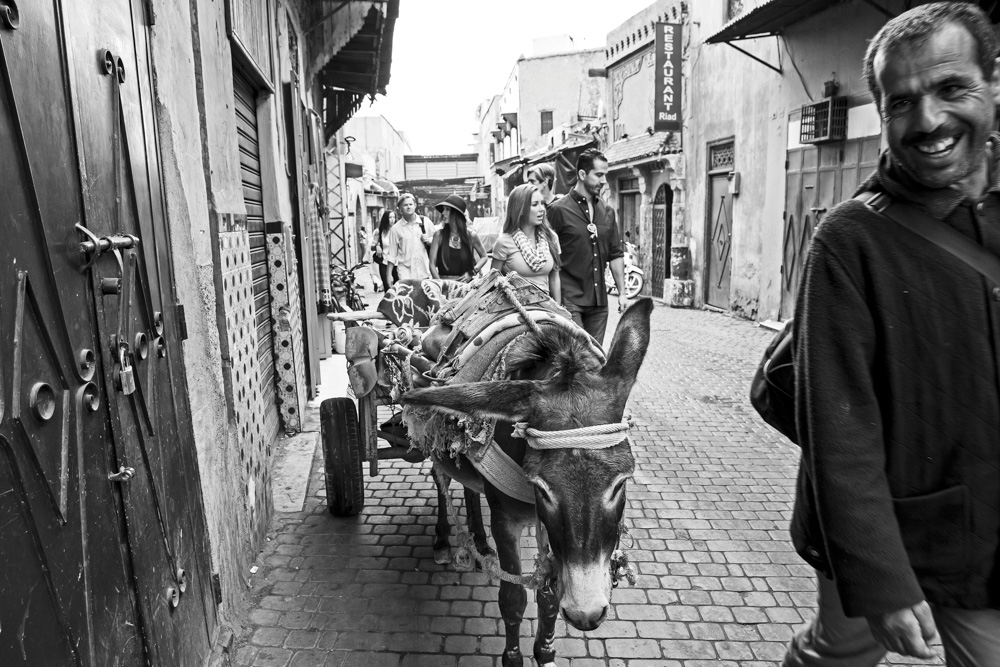

More than 9,400 alleyways crisscross through the medina in Fez, and weighed-down donkeys still deliver goods to the shops here every day, as they have for centuries. After all, there’s no other practical way for deliverymen to navigate these tight, hilly corridors.

Hassan, our local Muslim guide, took us on an excellent tour of the old city. Among many other things about daily life in Fez, we learned much about the very close relationship between Muslims and Jews.

“The Jews and Berbers were here first,” said Hassan. “When our Jewish neighbors celebrate their holidays, we cook food for them and bring it to their house. They do the same for us on our holidays. They watch our children, and we watch over theirs. We are all friends. Only in the media are we enemies.”

Each interconnected neighborhood in the medina has everything one needs to enjoy a good life: a bakery, a school, a hammam (spa), a mosque, and a freshwater fountain. All of these can be found within a few steps of the average home, so that even small children and the elderly have access with minimal effort. In the old days, large wooden gates could be closed between neighborhoods at night, ensuring that children were safe and sound among their immediate neighbors. They could also be closed to prevent intrusion, more often from disease than marauders. Today, though, such gates are unnecessary. Toddlers wander the streets by themselves. “Perfectly safe, as they have been for centuries,” said Hassan, patting young ones on their heads as they darted around us and warmly shaking hands with old acquaintances he passed in this city of a million friends.

Our final day in Morocco required a five-hour cross-country drive from Fez to the port of Tangier. The scenery in North Africa was both beautiful and surreal, but we were all secretly preoccupied with what waited for us just across the Mediterranean—two weeks of additional indulgence in Spanish wine, tapas, and nightlife.

Unfortunately, through a series of miscommunications and mishaps, we found ourselves at the right TIME but at the wrong PORT in Tangier—a full hour’s drive from our proper point of departure. We missed our ferry, which was obviously a critical juncture in this twelve-hour travel day from Africa to Seville. So, in a mad scramble to try to make the next connection, we strapped our luggage into the open trunk of a dilapidated taxi, crammed ourselves inside and dashed along the cliffy African coastline like contestants in The Amazing Race.

When we rolled into the parking lot at the proper port, we could see the next ferry gearing up to depart for Europe. Missing it meant spending many more hours in Morocco and quite possibly angering the driver who we hoped was still waiting to pick us up in Tarifa, Spain.

We bought our tickets and ran toward the departure gate. “No problem,” said a friendly local with a reassuring smile. “I will help you.”

“Thank you so much,” I said. “We have a very long day of travel ahead, and we already missed our first ferry.”

“No problem. This man is very important,” he said, gesturing to a uniformed terminal official. “He will hold the ferry for you, if you give him a little money. He will make sure that the ferry waits for you.”

“Yes, of course,” I said, fishing for my wallet. I had some extra dirhams that I would have to exchange anyway. I gave them each a generous amount and thanked them profusely as they helped our group quickly navigate through the immigration paperwork and security checkpoint. Once through the gate, it was an immense relief to round the corner and see the ferry still dockside. But, as we raced down the gangway, a mere fifty feet from our goal, the ship suddenly throttled up and began to pull away from the shore.

That son of a… They didn’t hold the ferry for us. They scammed us, and now we were on the wrong side of the security gate, with no way to get back through. I felt the group’s morale plummet. Two minutes faster and we’d now be on our way to Spain.

Such is the roller-coaster ride of international travel. If you enjoy the leisurely loop of a carousel, go to Disney World, Sandals, or Atlantis. It’s certainly fun, much safer, and much more predictable. You’ll no doubt return home rested and relaxed. But once you’ve gotten a taste for the thrill of a roller coaster, the carousel can lose its luster. While the unpredictable ups, downs, twists, and turns of international travel can be nauseating and gut-wrenching, once you’ve emerged unscathed, it’s hard to ever look at the carousel the same way again.

With our ferry churning off toward Europe without us, we turned around in fatigued defeat and slowly dragged our luggage back up the gangway. I looked up at the majestic African mountains in front of us and couldn’t help but smile.

“Welcome to Morocco.”

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE