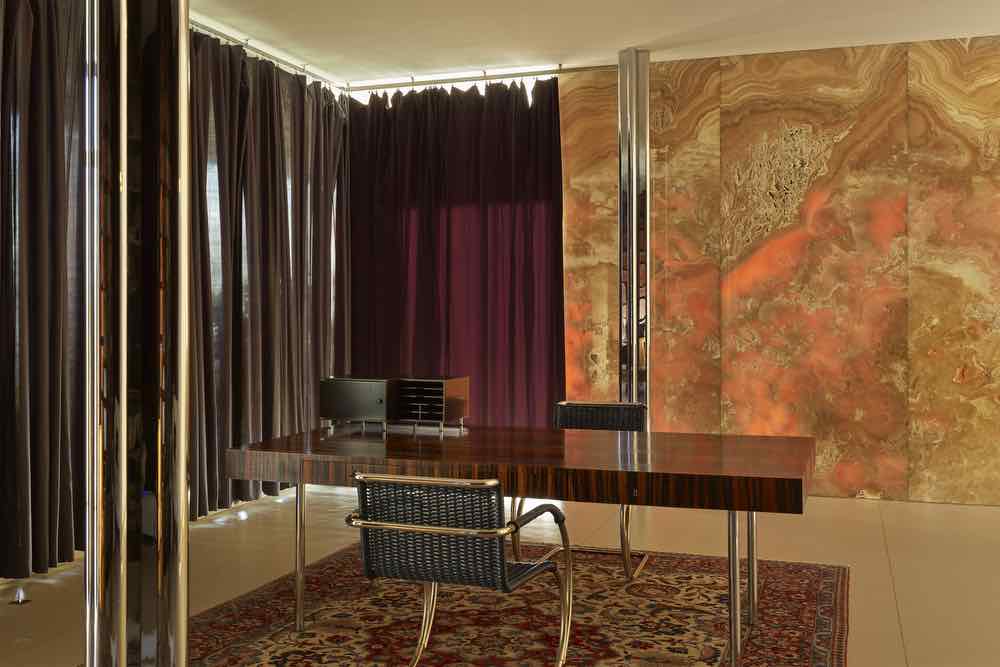

Brno,,Czech,Republic,-,Circa,October,2013:,Main,Living,Room

Villa Tugendhat in Brno, the Czech Republic | Photo by lulu and isabelle/Shutterstock

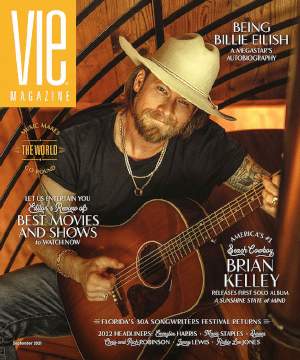

Saving Villa Tugendhat

Mies van der Rohe’s Architectural Treasure in Brno

By Anthea Gerrie

I am standing in a huge glass room that floats as if by magic over the long-sloping garden below, mesmerized by a floor-to-ceiling onyx wall that seems to be catching fire. Flickers of red and orange ripple across its pale gold surface as the sun sinks in the sky, randomly piercing its translucence on a bright spring afternoon in Mitteleuropa.

The onyx, which cost as much as four regular houses for a single slab hewn from Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, is the star feature of a home built nearly a century before today’s six-figure kitchens and infinity swimming pools came on the scene to impress visitors. But the intention was the same; Mies van der Rohe may have spent his working life insisting “less is more,” but that did not stop the architect from sourcing a dazzling expanse of semi-precious stone when he created the fabulous, futuristic Villa Tugendhat for a wealthy couple who granted him an unlimited budget.

The onyx, which cost as much as four regular houses for a single slab hewn from Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, is the star feature of a home built nearly a century before today’s six-figure kitchens and infinity swimming pools came on the scene to impress visitors.

Villa Tugendhat is reason enough alone to travel to Brno, which led the country in embracing modern architecture in its golden age—the twenty years between independence in 1918 after the break-up of the Habsburg Empire and the brutal seizure of Czechoslovakia by the Nazis. It’s one of six fine pre-war villas tourists can visit, but the only one with ten-foot-high, twenty-foot-wide windows retractable to the floor at the touch of a button to allow the outside in, the very essence of Frank Lloyd Wright’s philosophy of blurring the boundary between house and garden. Mies van der Rohe’s revolutionary steel frame enabled him to offer Fritz and Grete Tugendhat a reception room without walls—the onyx is an interior, non-load-bearing partition offering privacy by closing off the library space where Fritz conducted business while Grete entertained guests by pointing out landmarks on the Brno city skyline in the distance.

Photo by David Židlický

The richness of materials is the first thing you notice—not even the onyx can eclipse the striped Macassar ebony enclosing the semicircular dining area, its pearwood table expandable to seat eighteen, the massive ten-foot rosewood front door, or the brilliant red velvet upholstering the world’s first tubular steel chaise longue. It’s one of many signature pieces designed for the house by van der Rohe in concert with his longtime collaborator, Lilly Reich (their Tugendhat and Brno chairs created specifically for this showpiece villa are classics still in production).

This room came as a shock to the great and good of Brno, who only discovered it after entering what looks from the street like a handsome but modest single-story building (the 28,000-square-foot house actually has three floors) and descending a gently spiraling travertine staircase. It must have been a delightful daily respite to the Tugendhats, who started their days in an intimate suite of wood-paneled bedrooms and bathrooms with proper walls and doors before convening for meals in their glass eyrie below. But their idyll was cut short after just eight years by Nazi persecution, forcing the Jewish family to flee for their lives. They failed to achieve restitution of their property after the war.

Mies van der Rohe may have spent his working life insisting “less is more,” but that did not stop the architect from sourcing a dazzling expanse of semi-precious stone when he created the fabulous, futuristic Villa Tugendhat for a wealthy couple who granted him an unlimited budget.

The fact Villa Tugendhat has been saved for the world—in part thanks to Grete Tugendhat sharing the secrets of its original design with Mies van der Rohe’s Chicago studio to get renovation efforts underway—is a miracle. The house was abused in the intervening years between the family’s flight in 1938 and Grete’s brief return with Mies’s grandson, Dirk Lohan, in 1967. The gestapo looted the mansion, bricked up its gorgeous curved white glass entry wall, and destroyed many of the fittings when they took possession, followed by the Russian cavalry, who brought in their horses less than a decade later. Reconstruction was not attempted until the 1980s, and it was first done inauthentically. The proper nine-million-dollar renovation to van der Rohe’s plans did not start until after the millennium.

Still, the house’s most valuable and impressive fixture—that amazing wall of onyx—remained protected from every generation of intruders by the boarding-up, which the Tugendhats cannily arranged to conceal and preserve it for the future before leaving their dream home forever.

— V —

Find more information on the villa at Tugendhat.eu and VisitCzechia.com.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE