vie-magazine-frank-lloyd-wright-hero

Monona Terrace in Madison, Wisconsin, was first designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935, but was rejected and went through many drafts before his death. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the city built the structure, which was completed in 1997. Photo Courtesy of Visit Madison

The Artistry of Architecture

Making the World Beautiful

By Jordan Staggs

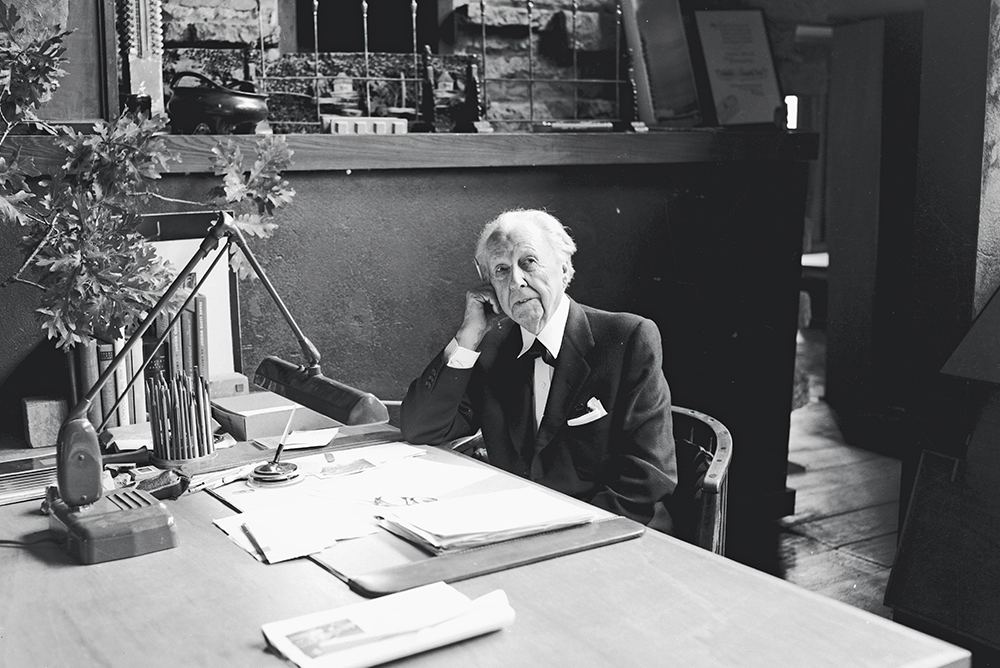

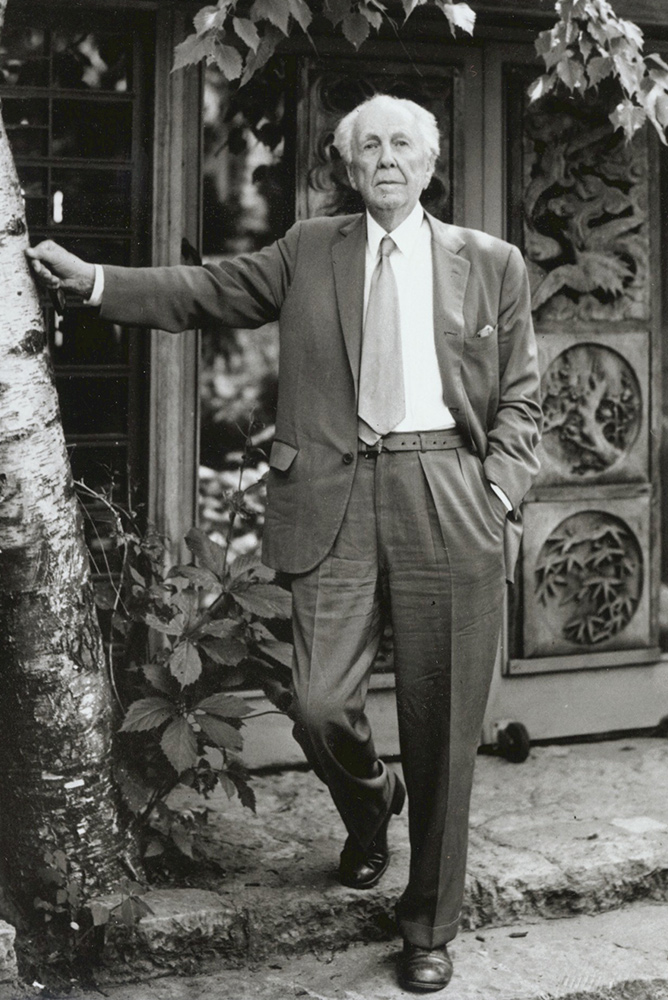

For admirers of modern architecture, there’s one American name that tends to stand out from the rest. Frank Lloyd Wright—born Frank Lincoln Wright on June 8, 1867, in Richland Center, Wisconsin—designed over a thousand structures before his death in April of 1959. Wright’s multifaceted talents as an architect, an author, and landscape designer, touched the lives of countless others in his lifetime. And, his influence is far from faded, especially in America’s heartland where the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail opened earlier this year.

A project spearheaded by Travel Wisconsin along with Taliesin Preservation, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Visit Madison, and others, the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail honors the architect with a nine-stop tour of structures he designed, and it opened just in time to celebrate what would have been his 150th birthday.

Drawing discerning fans of architecture and visitors looking to experience the American Midwest (along with its beer and cheese!), the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail is a little-known gem that includes beautiful landscapes and coastlines, regional fare, metropolitan experiences, and, of course, breathtaking structures designed by Wright and others. The first stop for those flying or driving from the East Coast is Milwaukee.

Frank Lloyd Wright. Photo Courtesy of Taliesin Preservation

Burnham Park

Though he was the master of Prairie-style architecture, Wright longed to develop sustainable homes for low-income families. His urban-planning model was known as the American System-Built Homes, the original six of which were built along Burnham Street in Milwaukee from 1914 to 1917. The idea was to build beautiful yet affordable homes in a community consisting of seven models from which residents could choose. Unfortunately, as the United States entered World War I in 1917, the lack of building materials and a disagreement with Wright’s partner on the project, Arthur L. Richards, brought the American System-Built Homes plan to a grinding halt.

Today, the six original Burnham Street residences are on the National Register of Historic Places, and tours of the Model B1 cottage are available most Saturdays and some Fridays throughout the year. The cottage exemplifies many of Wright’s signature traits, such as cantilevered rooftops, horizontal accent lines, and rows of windows wrapping the house.

Just about twenty-five miles south of Milwaukee on the edge of Lake Michigan are the next few stops on the trail including the quaint downtown district of Racine. North Beach and the town’s charming harbor and marina, Wind Point Lighthouse, are reasons enough for visitors to seek a holiday on the Great Lakes, but those on the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail will find architectural treasures hidden throughout the town. For the best view of the marina, stay at the newly renovated DoubleTree by Hilton Racine Harbourwalk, which is a short walk to downtown shopping and superb dining, such as local fare at Reefpoint Brew House and the Yardarm Bar & Grill.

Hardy House

Though it may not be an official stop on the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail, the Hardy House in downtown Racine is worth a look when on Main Street. Overlooking Lake Michigan, the home Wright built for Thomas P. Hardy and his family in 1905 looks somewhat like a box from the street side, but the expansive windows and partial basement overlooking the lake are real showstoppers.

Wright’s desire for every home to connect with nature as seamlessly as possible is evident in his use of glass, often even connecting glass panes to one another at corners for views unobstructed by pillars or beams. He was known for his use of glass and reflected sun rays to cast playful light spectrums onto floors and walls. “He had an uncanny sense of what light would do at different times of day,” says Mark Hertzberg, author and photographer of Wright in Racine, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hardy House, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s SC Johnson Research Tower.

- The SC Johnson Research Tower, with fifteen floors, is one of the world’s tallest structures built using the cantilever principle. Photo by Brianna Wright/Real Racine

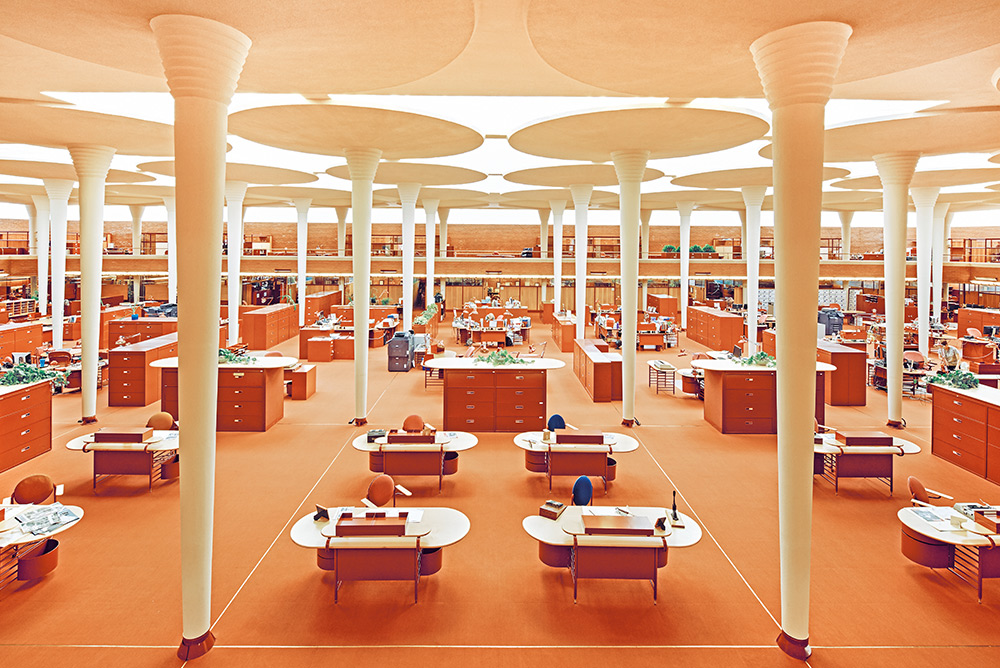

- The Great Workroom at the SC Johnson Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin, is a wonder to behold. The dendriform columns and custom furnishings reflect the building’s curvature. Photo Courtesy of SC Johnson

SC Johnson Administration Building and Research Tower

Few outside the architecture industry are familiar with Wright’s Midwestern commercial projects at the SC Johnson campus in Racine. Its sleek brick facade—in Cherokee red, Wright’s signature color—might seem like a departure from the architect’s desire to fuse buildings with their natural surroundings, and that’s because it is. “Most of Wright’s residences faced ‘out’ into nature,” Hertzberg explains, “but his public offices often faced ‘in,’ toward each other.” This kept the campus unified and promoted a synergy between its buildings, essentially turning it into a gated community for employees.

In 1936, SC Johnson leader H.F. “Hib” Johnson Jr. commissioned Wright to design a new worldwide headquarters that would reflect his third-generation family-owned company’s dedication to providing an exceptional work environment for its employees and exceptional products for its consumers. Wright’s plans for the SC Johnson Administration Building were met with challenges and some skepticism, especially regarding the canopy-inspired Great Workroom. At only nine inches in diameter at the base and over eighteen feet in diameter at the top, the striking dendriform columns can support about sixty tons each and are a testament to Wright’s brilliance. “The only computer he had to work with was the one between his ears,” Hertzberg says.

The administration building opened in 1939, followed by the adjoining SC Johnson Research Tower in 1950. The tower is one of the tallest structures ever to be built using the cantilever principle. A central concrete core thirteen feet in diameter extends fifty-four feet into the ground. The tower’s fifteen floors are built like the branches of a tree, supported by the core “trunk” which also contains the tower’s restrooms and elevator. Its windows, like those in the administration building, are made of Pyrex glass tubes, which refract light and cut down on glare. Still, the tower’s seventeen miles of windows meant sweltering temperatures and bright sunlight, prompting employees to nickname it the “Helio Lab” and to wear sunglasses while working. SC Johnson scientists have created Windex, Glade, Pledge, and other worldwide household products in this tower.

“Anybody can build a typical building,” said Johnson. “I wanted to build the best office building in the world, and the only way to do that was to get the greatest architect in the world.”

That isn’t to say Wright and Johnson didn’t have any problems. The buildings’ construction costs went well over budget—a habit Wright was infamous for—and leaks in the ceiling and windows meant employees often had buckets strewn about on rainy days. The original three-legged chairs designed for the workspace notoriously tipped over, which happened often enough for Hib Johnson make Wright redesign the chairs.

Still, the SC Johnson campus is notably one of Wright’s best and personal favorite works, as evidenced by his signature on a painted block gracing the main entrance to the administration building. (He only signed the structures in which he took the most pride.)

Also on the campus tour is Fortaleza Hall, home of the employees’ cafeteria and lounge, The SC Johnson Gallery: At Home with Frank Lloyd Wright rotating exhibit, a gift shop (in case you forgot to pack your Windex), and a beautiful re-creation of Hib Johnson’s twin-engine Sikorsky S-38 seaplane and a map of its 1935 journey from Milwaukee to Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. At the campus entrance is the Golden Rondelle Theater, which was constructed by Taliesin Associated Architects for the company’s 1964–1965 New York World’s Fair exhibition. It offers showings of Carnaúba: A Son’s Memoir, the documentary film of Sam Johnson Jr. re-creating his father’s seaplane expedition, and the Academy Award–winning short film To Be Alive!, which debuted inside the structure at the World’s Fair.

- This vertical fireplace at Wingspread Estate is a striking feature—despite its practical shortcomings. Photo by Jordan Staggs

Wingspread Estate

Wright’s second design for Hib Johnson was the Wingspread estate in 1939, the home of Johnson and his family. Having fourteen thousand square feet of floor space, this pinwheel-shaped residence in Racine’s Wind Point neighborhood is the largest private residence designed by Wright.

This stop on the trail is a treat for those who love stories, as docents recount the tales of Johnson and his family, along with Wright’s antics. A favorite among visitors is the time Johnson was seated at a dinner party when the roof began to leak. (Wright’s designs were innovative but not without flaws, and this seemed to be a common one.) The water was dripping right onto Johnson’s head when he yelled for someone to get him the telephone and barked at the operator to connect him with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona. The dinner party was silent as Johnson berated Wright for building him a house with a leaky roof, telling him about the current situation. Then, they clearly heard Wright tell Johnson, “Well, Hib, move your chair.”

The home and grounds are stunning, blending with the hillside and overlooking a pond. Its cantilevered “Romeo and Juliet” balcony was designed especially for Johnson’s daughter, Karen, of whom Wright was very fond. Perhaps the property’s most unique feature is the thirty-foot central chimney, which also has a glass-domed watchtower at the top. The main living areas of the house wrap the chimney, which contains four fireplaces, including an unusual one in which Wright suggested placing vertical birch logs. Sam Johnson Jr. said the first time they tried using it, a burning log fell into the room and had to be dragged outside and pushed off the balcony to avoid a house fire. Needless to say, that fireplace became purely decorative.

Today the Johnson Foundation operates within the twelve-acre estate, using the property for conferences and workshops along with public tours. “It’s a place for us to bring people together,” says Roger C. Dower, president of the Johnson Foundation at Wingspread. “Day to day, we think about this place as a tool and how we can use it as a foundation.”

Before you head out of town, don’t forget to stop by O&H Danish Bakery for some Nordic flair and the region’s most prized confection—the kringle! This flaky, buttery pastry will tide you over until lunch in Madison, where a stop at DLUX burger bar or The Old Fashioned tavern wouldn’t be complete without a side of Wisconsin cheese curds.

Wright designed the First Unitarian Society Meeting House in Madison to resemble a plow, reflecting the city’s roots as a farming community. Photo courtesy of Visit Madison

First Unitarian Society Meeting House

One of Wright’s most personal projects, the First Unitarian Society Meeting House in Madison, is recognized for its significant role in shaping American architecture. Wright’s father was a preacher at the church, whose meeting hall roof extends like the bow of a ship, while windows below jut outward and down, coming to a sharp point like a plow. These were significant design elements of Wright’s Usonian designs, which he called “democratic architecture.” This meant they were built using locally sourced natural materials and, as he explained, “true to the time, the place, and the name”—Usonia being an acronym for the United States of North America.

Today the meeting house remains a gathering place for all sorts—with the First Unitarian Society graciously lending its halls to those in need and renting out space to other groups and events.

Monona Terrace hosts conventions and other events, offers dining on the rooftop terrace, and affords spectacular views overlooking Lake Monona. Photo courtesy of Visit Madison

Monona Terrace

Across the city from the First Unitarian Society, Monona Terrace is perhaps Madison’s most prized architectural possession, aside from its stunning (and imposing) Wisconsin State Capitol building. Wright first proposed the project of his “dream civic center” to the city in 1935, and the terrace’s design went through many iterations but was never realized in his lifetime. Its completion in 1997 created a gathering spot for all of Madison’s citizens to enjoy the views of Lake Monona, a café and gift shop, and space for meetings, events, conferences, weddings, and more. The surrounding walkways are perfect for cycling or running, while the rooftop terrace affords views of the lake and is ideal for spectators to witness water sports, sailing, and the swim portion of the IRONMAN 70.3 Wisconsin triathlon.

Worth another stop for travelers with children—or for those who are just young at heart—is the Madison Children’s Museum and its 2017 exhibit From Coops to Cathedrals: Nature, Childhood, and the Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, which tells the story of young Frank Lloyd Wright and offers several activities for kids of all ages.

Middleton is a good headquarters for those staying overnight, conveniently located on the western edge of Madison, between the city and the beautiful rural landscapes of Spring Green.

- Taliesin was Wright’s personal residence and studio on the eight-hundred-acre estate. Photo by Caroline Hamblen, courtesy of Taliesin Preservation

- The dam at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, was designed by Wright to create a scenic pond that can be seen from his residence and a waterfall, which pumped water to the house. Photo Courtesy of Taliesin Preservation

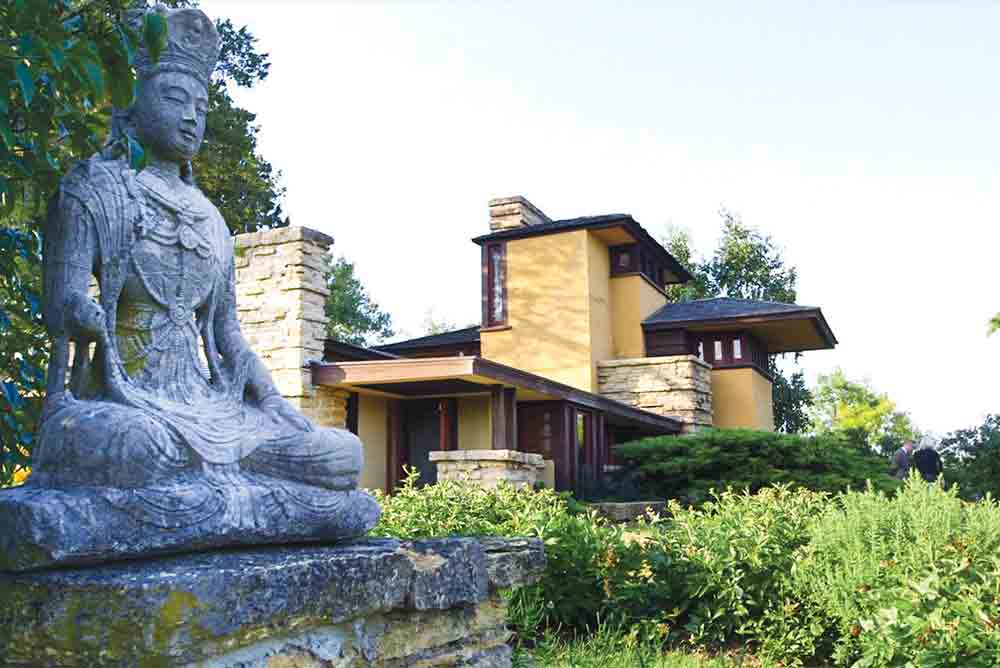

Taliesin Estate and the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center

Wright’s Wisconsin roots were strong as he was born and raised there, attended the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and lived and worked in the Spring Green area for many years. His private residence and studio and the Hillside architecture school lie spread across the eight-hundred-acre Taliesin Estate, just about an hour’s drive west of Madison.

The first stop on the estate is the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center, housed in a unique bridge-like building overlooking a valley beside the Wisconsin River. Originally a fine dining restaurant, the Visitor Center still houses the Riverview Terrace Café and the Taliesin Bookstore, a gift shop containing everything from Taliesin T-shirts and novelty items to handcrafted replica light fixtures based on those at Wright’s home on the estate. The Visitor Center is where all tours begin, and visitors are guided by knowledgeable docents who are passionate about the estate and full of fascinating stories along with facts about the architecture. Taliesin Preservation has worked hard in a noble effort to keep the property running and to share its legacy with visitors and students.

Hillside is a school designed in 1902, originally a gift to Wright’s aunts who ran an innovative hands-on learning center for children. It later became the site of Wright’s architecture school, where his apprentices lived, worked, and studied. He carried on his aunts’ motto of “learn by doing”; his students designed and built structures around the property, repaired and improved existing ones, did all the chores and upkeep for the school, and even did farmwork and helped with the preparation of meals. Each time there was a banquet, Wright tasked a student with designing a new layout for the dining hall’s tables and chairs, all of which were designed by Wright, like most furniture in his buildings.

The Hillside School was a significant piece of work since it was the first time Wright “broke the box”—that is, designed a building to have non-load-bearing outer walls. Instead, the roof and ceiling are held up by interior support columns, which allowed Wright to wrap the assembly hall with large windows, blending the interior into the natural landscape and keeping the structure from feeling like an enclosed box.

The drafting studio at Hillside is still in use: apprentices of the Taliesin architecture programs train there during summer to design impressive architectural works of art; in winter they work at the Taliesin West campus. The building also includes a museum-like exhibit of photography by Pedro E. Guerrero, Wright’s personal photographer.

Wright’s brilliant yet impulsive, and at times curmudgeonly, nature dictated that while his life was marked by great work and deserved fame, it was not without scandal, and some of the most scandalous events in it occurred at his home at Taliesin. After leaving his first wife, Catherine, and their six children for Europe with a woman named Mamah Cheney, Wright’s reputation as a ladies’ man took a turn for the worse. Cheney’s husband—a client of Wright’s—granted her a divorce but Catherine refused, and so when they returned to America, Wright and Cheney moved to his secluded country home at Taliesin in 1911, which was still under construction.

Though they were never married, Wright and Cheney had a presumably happy relationship, and Cheney lived at Taliesin for three years before tragedy struck both the family and the property. On August 15, 1914, a deranged former employee at the estate named Julian Carlton set fire to the home after locking all the doors but one. When Cheney, her two children, and four others tried to escape the burning building, Carlton murdered them all with a hatchet. The incident devastated Wright and severely damaged the residential wing of the home.

A presumed electrical fire in April of 1925 again wiped out most of Taliesin’s living quarters, but Wright soldiered on to rebuild both his life and his home. The building stands proudly today as its name (Welsh for “shining brow”) is evidenced in the way it drapes across the hillside overlooking the river and the waterfalls designed by Wright. The four-hour walking Estate Tour of Taliesin also includes a look into Tan-y-Deri, the more traditional-style home Wright built for his sister Jane Porter, the nearby Romeo and Juliet Windmill, and a walk past the Midway Barn, which served as housing not only for livestock but later for architectural apprentices.

“Taliesin is not a museum, it’s a cultural center,” explains Erik Flesch, a former student of the Hillside architecture school and now director of development for Taliesin Preservation. Events and tours are held throughout the year, a fact that Flesch and events director Aron Meudt-Thering say most people don’t realize. Private dinners, talks in the Hillside Theater, educational and children’s workshops, al fresco dining experiences, and even horse-drawn carriage rides in winter are at Taliesin, waiting for locals and visitors to discover this culturally rich gem nestled in the hills.

The Wyoming Valley School

Just a short drive from Taliesin is another stop along the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail, the Wyoming Valley School. The symmetrical building includes two classrooms and an assembly hall. It was a gift from Wright to the school district made in honor of his mother, Anna Lloyd Jones, in 1957. It is the only public school building designed by Wright and, although modest, includes many of his staple architectural elements—a central fireplace, windows wrapping the building, long horizontal lines, and a rural hillside setting perfectly suited to the design. Today, the building is home to the Wyoming Valley School Cultural Arts Center, which hosts events and programs throughout the year.

Head west for the final stop along the trail as the official tour ends in Wright’s hometown of Richland Center, Wisconsin.

A.D. German Warehouse

This four-story warehouse, commissioned by Albert D. German and completed in 1921, is Wright’s only commercial work in his hometown. A frieze of repeated cast concrete motifs rings the building’s rooftop, and the warehouse is considered Wright’s best remaining example of sculptural ornamentation since the demolition of Midway Gardens in Chicago and the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Originally used for the storage of sugar, flour, coffee, tobacco, and other commodities, today it houses a gift shop, a small theater, and an exhibit of large murals illustrating Wright’s architectural work.

Although one could probably never see all 532 of Wright’s completed works in one lifetime, the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail is far from the end of the line for those who wish to see more. Wright-designed homes and public buildings are open for tours around the world, but the most up-close and personal look into the architect’s brilliant yet controversial life is found in southern Wisconsin. Wright often said that his favorite design was “my next one,” and his legacy of looking into the future is alive and well in the people who work tirelessly to preserve his past.

—V—

Visit TravelWisconsin.com/Frank-Lloyd-Wright, SCJohnson.com, and TaliesinPreservation.org to learn more about the Frank Lloyd Trail and start planning your trip.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE