vie-magazine-nick-racheotes-hero-min

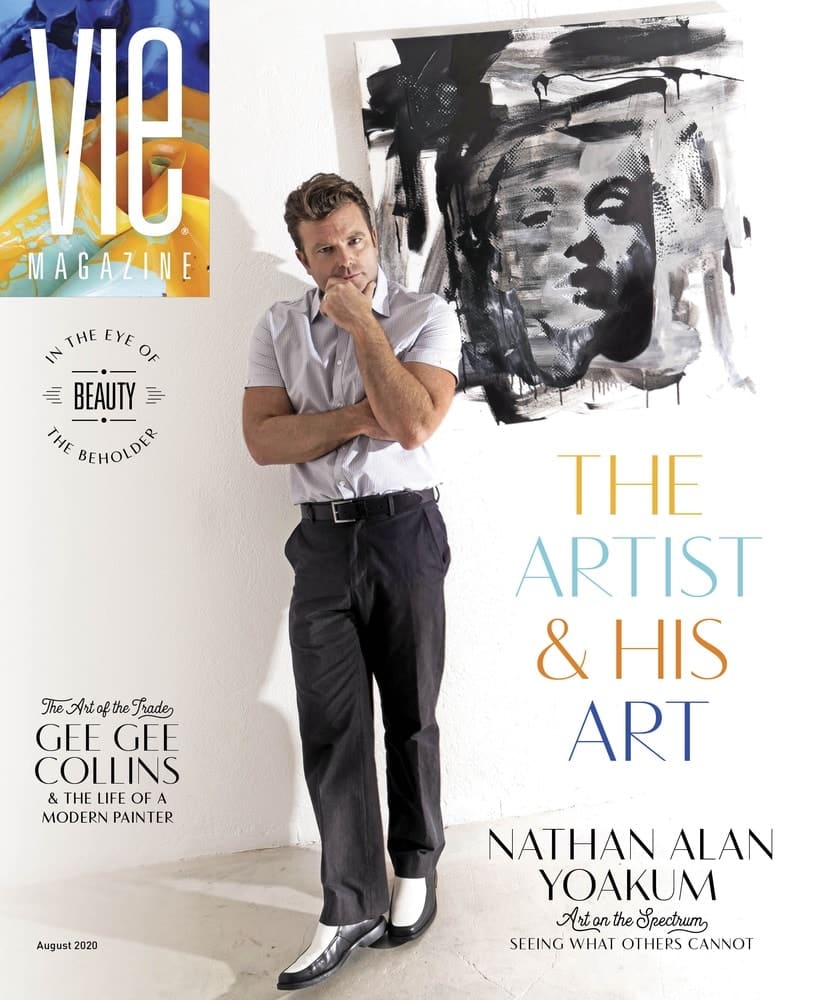

The Architectonic Boom

The Art of the Skyline

By Nicholas S. Racheotes | Illustrations by Lucy Young

It’s high time an article began with a five-syllable word in the title. Why boom, though, when no jet is breaking the sound barrier and rattling the dishes in houses unfortunate enough to be on the flight path? The explanation for boom lies elsewhere, so get ready for a reach. The universe is 13.8 billion years old, according to the calculations of the latest big bang gang, but humans have only been blanketing it with megalopolises and urban skyscrapers for a century and a half.

Now, let’s play a mind game in which there are no losers: imagine living on a comet that returns within sight of the earth every so (or not so) often. Up until the nineteenth century, we would have seen a certain number of walled cities, fortresses, and palaces built to show the power and personality of kings and emperors. Of course, there were other magnificent structures erected over many generations by persons who wished to “do something beautiful for God,” in the words of Mother Teresa. Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, Sultan Ahmed’s Blue Mosque in Istanbul, Saint Peter’s in Rome, and Chartres Cathedral outside Paris were such timeless examples of design and symbols of faith that they became places of pilgrimage. Would we say the same about the temporary multimillion-dollar pins that try to deflate the sky in New York City, Chicago, or Shanghai? Are we awestruck by Dubai’s Burj Khalifa or the eventual Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia? All those sound to me like a long elevator ride with little prospect of spiritual uplift.

The concept that we like to apply to such tributes to human engineering and hubris is “iconic”; however, that term has been used with such elasticity as to be stretched thin enough to read a newspaper through, if anyone still reads newspapers. The twin towers in New York and Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem were iconic because they were tragically destroyed. The Empire State Building is iconic because King Kong swatted airplanes from its spire.

In the nearly obsolete but revered libraries of our major universities, we find cubicles where the world’s greatest ideas were birthed and where they later expired from disuse. Instead, the nebulosity of the web and the cloud, given added life by the wide-open spaces and conversation pits of think-tank construction, mean the dwarfing of the solitary thinker’s stature. We now float in what appear to be new spaces. Are these as impermanent as the notions they spawn?

A basic question eats at the foundation of every skyline: what are you communicating? The bells from the many churches of Moscow were proclanging, “This is as close on earth as you will get to the sound of heaven.” We may remember what George Orwell was putting in the intoxicated memory of Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “Oranges and lemons say the bells of Saint Clement’s.” We might even listen with a measure of reverence to how Pete Seeger played this idea into the prolabor anthem “The Bells of Rhymney.”

Today, the buildings are silent, permitting us to speak for them. It’s a shoe! No, it’s a boat! No, it’s the New Balance headquarters in what is lovingly but somewhat misleadingly termed Brighton Landing, near but not on the Charles River. Now beauty, if such it is, is in the eye of the financial backer. What would John Hancock have said should he have beheld the tower bearing his name covered with plywood because the designers had not reckoned on those mighty winds in Boston’s Back Bay creating an effect that caused the first generation of windows in the tower to fall like snowflakes in a nor’easter? Eventually, the problem was corrected, but not before liberal and illiberal doses of scorn were heaped upon architects I. M. Pei and Roy Barris.

Let’s go back to our comet for a moment. What would we make of the race for inner and outer space? Do we ponder iconic Saint Paul’s Cathedral resisting the German blitz on London and think how mighty are the works of humanity when consecrated to the worship of its gods? Do we wonder whether the new deities—banking, insurance, and multinational corporations—have the same power to endure and inspire feats of design? Would we elevate Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, and their student Philip Johnson to the heights enjoyed by those who built the Parthenon, the Taj Mahal, or Angkor Wat? Might we comet riders dismiss the modernist and postmodern architects of the present and prior centuries as having forsaken the strength of marble and travertine for the impermanent materials of today?

Among our generation’s answer to the Athenian architects Ictinus and Callicrates are Philip Johnson and Frank Gehry. Under the discerning eye of their supervisor, the sculptor Phidias, the ancients made buildings that defied time but could not withstand the shells of the Venetian fleet that fell on the Acropolis.

Johnson may have thought of design in sculptural terms. He actually lived in a glass house of his own design in New Canaan, Connecticut. (Presumably, the only stones he threw were verbal.) With various partners, he poured his creativity into his projects: the bronze-and-glass Seagram Building, the twice rechristened 550 Madison Avenue, the Lipstick Building, and Lincoln Center in New York; Pennzoil Place in Houston; the Crystal Cathedral in California, and so many others. Johnson said, “We still have a monumental architecture. To me, the drive for monumentality is as inbred as the desire for food and sex, regardless of how we denigrate it.” What would Mother Teresa have made of that?

As for Gehry, his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, attracted worldwide attention. Not only in Europe, but also from the campus of MIT to the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, his buildings are both original and occasionally controversial. As with the temples of Greece and Rome, they have obvious sculptural components.

From our comet, we might consider Martin Luther’s contention that a pope of conscience would prefer that Saint Peter’s burn to the ground rather than be “built up of the skin, flesh, and bones of his lambs.” However, when we look deeper into the competition among corporations, cities, and nations for their pieces of the sky, we learn of the tax breaks and zoning exemptions that make us taxpayers the real sponsors of monumentality.

In a sense, a skyline is a work of art. The people whose neighborhoods were destroyed to produce it are real. A design may adroitly combine nostalgia and innovation; nevertheless, those who work, live, study, or worship in the building must function, be contented, and even be inspired.

The obvious thing would be to do what is common in writing on architecture and give the last lines to Percy Bysshe Shelley and his poem “Ozymandias.”

I met a traveler from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

What we know is that “the lone and level sands” are just as likely to sprout with the lavish architectural dream of a self-styled mighty king as an urban landscape is to burst into brick, steel, and glass at the behest of an ambitious CEO and captivated board of directors.

Sad to say, Philip Johnson is no longer with us, but we can fashion our dialogue around what he might see in a crystal ball of his own making. Once upon an earlier century, Louis Sullivan and the Chicago School erected tall buildings in a single bound. William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer published dailies that were yellow and read all over. Will the challenges of a never-certain future mean that the towers scraping the sky at city center may, like the newspaper of the recent past, be flirting with obsolescence? The future of design may lie with the inner space of a renewed cottage industry. There, work will be “put out” to skilled artists, bankers, corporate moguls, and educators who join one another in secure clouds of information and shape the brave new atomized world. There will be no time wasted in long commutes and hunts for parking, no dressing for success, no water-cooler gossip, few opportunities for personally intimidating coworkers and subordinates, and no productive quietude in an environment that each worker has customized to their specifications. In this return to the preindustrial world, many of us will be working at home as we cultivate the ideas that robots apply in production centers specially designed for them. The air will be clean, and the only sounds one might hear are the church bells or the calls to prayer from the minarets of emerging states, reminding us of what seems to last.

— V —

Nick Racheotes is a product of Boston public schools, Brandeis University, and Boston College, from which he holds a PhD in history. Since he retired from teaching at Framingham State University, Nick and his wife, Pat, divide their time between Boston, Cape Cod, and the Western world.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE