vie-magazine-hero-chris-kent-2009

Seaside: A Beginning and a Return….

Sometimes I go about in pity for myself,

And all the while

A great wind is bearing me across the sky.

—Ojibwa saying

By Chris A. Kent | Photography by Jessie Shepard

There are times, places and circumstances that punctuate the arc of a career and alter the shape of a life.

If we are honest with ourselves, we accept that many of these opportunities were thrust upon us, unplanned and unexpected, seen at the time as vague byways or even overgrown paths. Yet, when chosen, seemingly irrelevant decisions can be transforming.

I have known such experiences in the Town of Seaside.

I am not alone. While so many were skeptical in those early days, to some of us Seaside represented a compelling story long before it was a physical reality. From 1984 until 1996, while overseeing the sales of Seaside real estate, I saw that story unfold firsthand, becoming a primary theme interwoven with the personal narratives of others who, like me, constellated in this one place at one time. We who were involved believed we were lead actors in shaping a piece of real estate. Yet, in hindsight, we can allow that we were carried along by an almost inevitable force. Seaside seemed a place in search of itself. The raw depth and breadth of its physical creation would ultimately contribute to, even demand, in many instances, a certain psychic completion in those of us who thought we were the ones bringing it to life.

If you have to ask what jazz is, you’ll never know.

—Louis Armstrong

I grew up living in two very different worlds.

The first world was linear and rational, typical of a small village in the Midwest—an equal mix of pleasant and stultifying, picking a way through childhood and adolescence in search of some degree of independence along the way. The second, an otherworldly place, was total immersion in music performance. Reconciling these two separate worlds at a young age created extreme opposites: scaling endless and oftentimes dizzying heights while plumbing equally painful depths, while those around me seemed unaware. The monotony and complexity of hours of practice pierced by momentary effortless performance breakthroughs, with no one hearing either. Participating in the indescribable melodic and harmonic textures of symphonic bands and symphony orchestras, after hours and sometimes days of waiting on and off stage in silence. Flights of freedom as lead horn riding within, then overhead and at times soloing beyond the disciplined chaos of a fine jazz ensemble, with off hours in pinball parlors and cheap suburban motels awaiting the next gig.

Life remained a delicate traverse through these two disparate worlds until after high school, when I was allowed to pursue the second world exclusively at the University of Michigan School of Music and Interlochen National Music Camp. Participating in classical ensembles of contemporaries approaching our individual instruments at ever higher levels. Performing compositions so transcendent and transcendently, that at times we felt we knew the 18th-, 19th– and 20th-century masters who created them. Pursuing those rare and exquisite moments when performers, performance and music become one. A rich musical experience that would culminate in a degree in music performance and more paid orchestral and jazz work. Yet, despite the exhilarating levels of performance, the subsequent intermixing with the business of classical music became sobering and Sisyphean, a seemingly soulless replaying of the same symphonic repertoire week after week to meet the demands of a paying audience with narrow expectations. The joy of creating music degenerated into simply a way to make a living. That special otherworld faded.

Chop wood, carry water.

—Zen saying

Burdened with this duty to “make a living” yet shaped from a young age by a performance culture that rewarded execution on demand, I plunged into business. A couple of fitful years in restaurants (the business equivalent of a witness protection program for those with only a music performance degree) led by chance to a position in general real estate brokerage. The next years were spent working my way through the ranks of a high-volume, high-energy brokerage firm under the watchful and unerring eye of an ex-Army armor officer who previously fought his enemies, real and imagined, with Creighton Abrams and Omar Bradley. That searing experience, equal parts grueling and invigorating, had a certain familiarity. The old musical mantra, “You’re only as good as your last performance” became “You’re only as good as your last deal.”

Yet there was something missing. In my music career at its peak, the act of performance was simply a means to an even more meaningful end, creating music. Real estate brokerage, on the other hand, seemed to value performance as both means and end, resulting in what seemed a relentless pursuit of execution with only secondary interest in the collective effect of that effort. Unlike the arts, there seemed so little to show from even a high level of performance, beyond the money. So after years sharpening my craft under that most difficult and brilliant of taskmasters while simultaneously trying to understand his periodic nonsensical ferociousness, it was time to move on. Now in control of my own career, the lingering sense remained— more a dull ache, really—that, even within my control, real estate brokerage for its own sake could become a dismal occupation. The joy of performance, previously the gateway to that second otherworld of music, also began to fade.

To fill the void, I read voraciously. Fiction was early sustenance. Steinbeck, Faulkner, Conrad, Melville, Homer, Miller, Twain, Hugo, Joyce, Blake, Cervantes, Hesse, Dante, Machiavelli, Dickens, Sinclair, Huxley, Haggard, Voltaire, Castaneda, London, Hemingway, Hardy, Dumas, Fitzgerald, Hawthorne, Mann, Thoreau, Goethe, Rilke, Eliot, Whitman, Nabokov, Chekhov, Camus, Kafka, Stevenson. Finely crafted portrayals of characters and circumstances, so different in time and place, yet all containing an underlying and unsettling sameness.

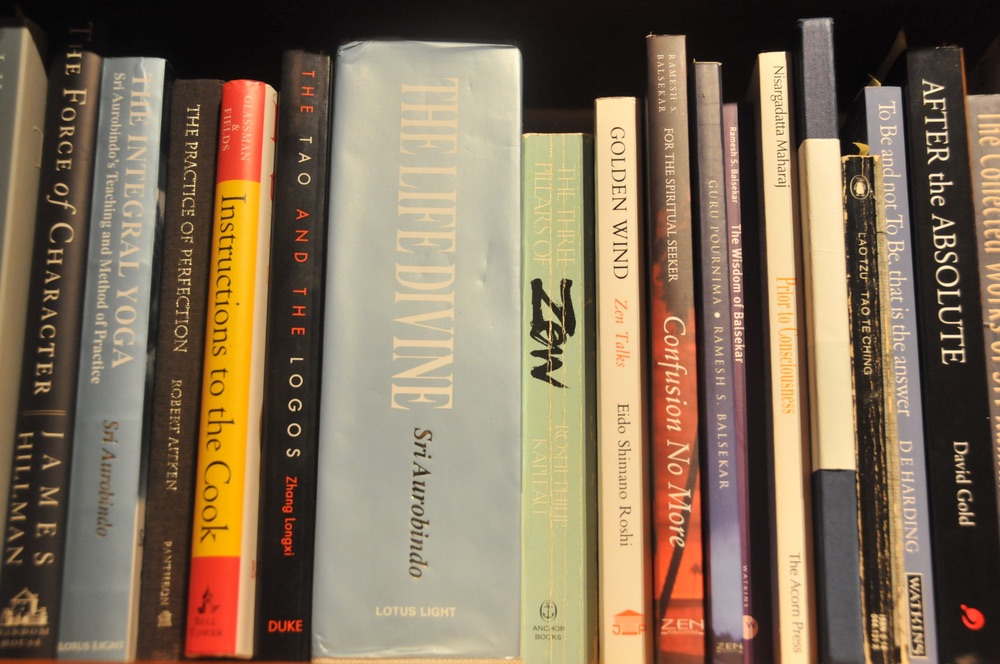

Pursuing this fundamental commonality led to psychology, anthropology, ethnology, philosophy and metaphysics. Freud’s courageous examination of the notion of the unconscious and methods for bringing it into consciousness through psychoanalysis. Jung’s connecting core human tendencies with the notion of a collective unconscious—underpinnings of his archetypal theories. Schopenhauer’s spanning the seemingly improbable connection between worlds of phenomenon and will. Campbell’s associations of mythology with cultural traditions of Eastern and Western cultures. Chuang Tzu’s all-encompassing approach to the notion of Tao. Hui-neng’s insight into original nature that would become a foundation for Chinese Chan and Japanese Zen.

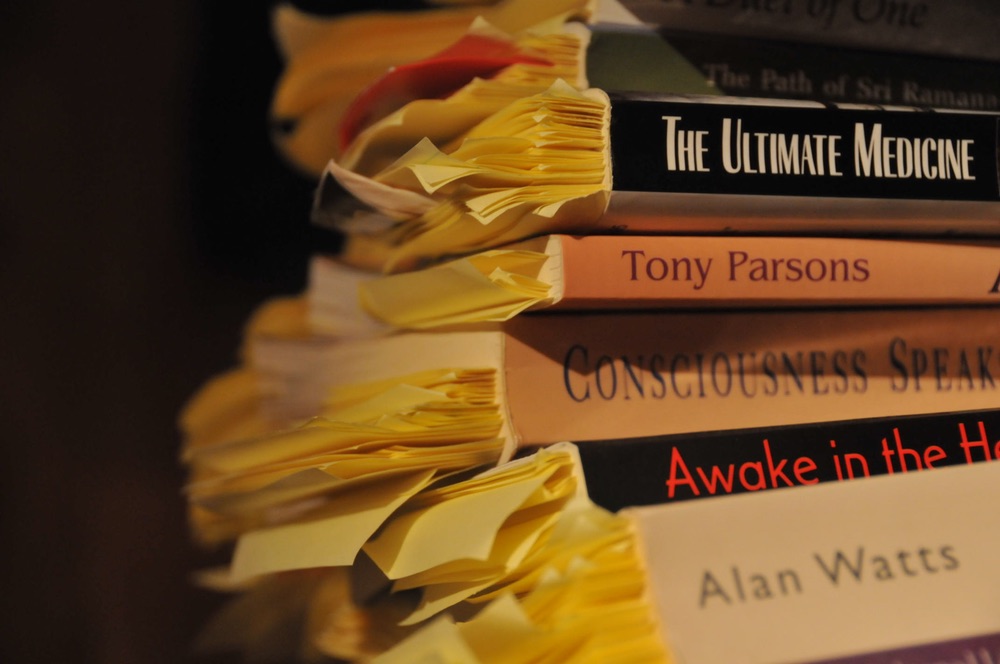

The list extended to psychological and dualist contemporaries. Nietzsche, von Franz, Wilbur, Jaffe, Hillman, Kabat-Zinn, Benoit, Capra, Singer, Neumann, Bly, Meier, Edinger, Johnson, Kubler-Ross, Wilmer, Van der Post, Fromm, Mindell, James, and others—leading deeper to non-dual apperceptions of Maharaj, Maharshi, Balsekar, Wei Wu Wei, Adamson, Liquorman, Krishnamurti, Aurobindo, Aitken, Glassman, Kapleau, Suzuki, Kornfield, Poonja, Klein, Om, Watts, Wolinski, Osborne, Godman, Herrigel, Swartz, Hanh, Sun Tzu, Parsons, Powell, Dunn, Loori, and Beck.

Again, life followed two distinct and disconnected paths: intense workdays in the brokerage arena broken by hours of reading and studying the workings of the individual and the collective, neither fathoming nor caring about any connection between the two.

Discovery consists in seeing what everybody else has seen and thinking what nobody else has thought. —Albert Szent-Gyorgyi

About that time, I bought a second home just down the beach from a few austere cottages and a beach café that were the beginnings of the Town of Seaside. Like most locals, I knew little of the place and even less of its ambitious intentions, beyond the Seaside Grill. “The Grill,” as it was known locally, was a cross between local roadhouse and beach bar fashioned from a couple of abandoned and transplanted Florida cottages placed ceremoniously in the salt-stunted beach scrub. With volleyball gulf side, a breezy bar of half a dozen or more stools and café seating for a few dozen more, it was to become the lone trading post in the sparsely populated hinterlands between Panama City and Destin. Scattered locals, inland characters, self-crowned philosophers, architects, contractors and laborers from a radius of thirty miles would congregate, swap stories, and eat well-prepared food served simply while watching the ebb and flow of visiting tourists straggle in and out. It was by any account a most delicious of sociological brews.

Arriving fresh from years of intense brokerage campaigns and near-monastic bouts of reading and study, the intermixture of simplicity, sophistication and raw human theater in early Seaside felt both familiar and exotic. Outdoor art movies, concerts and gatherings that I hadn’t seen since Ann Arbor and Interlochen. Structures, exterior space and interiors revealing an attentive approach to planning and design. An unrelenting attention to detail. The camaraderie among those interesting characters and their amused audiences frequenting the Grill. The raw audacity of building a new beach town where no town had existed. A location a short walk up the beach from my own place. All awakened a certain curiosity.

Soon after, I crossed paths with Robert Davis, the founder of Seaside, at an art film shown in the town’s small market square. Prior to our meeting, I had watched with interest from a distance as Robert, in his inimitably quiet and thoughtful manner, soldiered on in search of people and circumstances to further his ambitious undertaking. Within weeks he invited me to dinner. As he deftly prepared a remarkable Italian meal, we began a conversation simultaneously diverse, in depth and engaging. Woven within this interchange, his frustration and fatigue with sales at Seaside were palpable. With little interest in the process, existing sales operations had relegated him into the Faustian bargain of either selling Seaside by himself or turning it over to brokerage people with little understanding of its subtleties. This discomfort seemed further aggravated by his generous and charming habit of providing dinner for a number of prospective purchasers, in many cases cooking it himself in the meticulous manner of a Northern Italian native.

I quickly explained that I had no interest in another long-term brokerage job. Finally free after years of psychological and fiscal detention chasing brokerage fees with my early mentor, a position as “sales manager” for Seaside was not only unwelcome but abhorrent. I was beginning to enjoy the Grill and art movies from the safe vantage of my own place just down the beach. Why threaten the time-honored business rule of healthy separation between business and pleasure? Robert steadily and interminably pressed on, describing his present excruciating path of selling Seaside properties himself as equally repulsive. At times, it seemed that only a mutual affection for good food and conversation brought us together. We cooked, critiqued, sparred, cajoled, intellectualized and commiserated in a peculiar and fascinating dance of negotiation known to introverts. A few weeks later, unannounced, I received a note from Robert asking me to invent a job in Seaside that I would take.

While unexpected and seemingly unwanted, there was no denying the raw attraction of that offer. No preconceived job description, a proverbial clean slate. Hesitantly, irrationally, I proposed that I take over Seaside’s real estate sales operations as an outside contractor for one year. After that year, we’d reevaluate our relationship. If either of us was unhappy, we’d cancel our agreement and move on.

How refreshing, the whinny of a packhorse unloaded of everything!

—Zen Saying

Seaside’s existing sales operations proved daunting. While sales presentations resembled its competitors, the town planning and architecture were unlike any other real estate development. Homesites were significantly smaller than our competitors’ and considerably more expensive. Cottages were required to conform to strict architectural codes and it was more costly to build them. Early purchasers had to buy a homesite and finance it, hire a designer or architect to design improvements, arrange for a construction loan, engage a builder, complete construction to relatively high standards and obtain permanent financing when all construction was completed. Moreover, at a time when a house in the suburbs or on a golf course represented the predominant real estate development type throughout the country, neither an attached garage nor grass in the yard was allowed. As a “real estate development,” the place approached a nightmare.

Yet, psychological texts explain that nightmares and fears, when embraced, can lead to deeper understanding. And while the mainstream real estate community shunned our work in those early years, I saw in Seaside a profound opportunity. An occasion to abandon the extraverted “pleased to meet you” sales atmosphere that I had intuitively avoided for years. A laboratory to test whether people could understand and embrace depth and subtleties presented at a level beyond those found in a typical real estate brokerage office.

We forged ahead.

To begin, we needed a sales team with desire, raw ability and openness to this new unorthodox and unproven approach. Jacky Barker and Donna Spiers were available, thankfully, and over twenty five years later continue this role as the longest-tenured and respected employees today. Working closely, we shaped a nimble and capable brokerage organization based upon principles and practices honed from my years in the field. The ultimate structure, discipline and attention to detail to the brokerage side of the operation created a firm foundation upon which we could then introduce subtle layers of considered planning, vernacular architecture and community—all distilled into a brief logical narrative.

We reinterpreted Seaside’s plan from its academic origins into terms recognizable to our audience. A street grid’s providing ease of navigation while promoting the movement of sea breezes throughout the neighborhoods. Interrelationships between footpath and park systems for pedestrian circulation. The street’s role as a “room” for gathering and pedestrian interaction. Axial relationships terminating with monuments and beach pavilions, connecting neighborhoods with one another and the sea. Public buildings and civic squares as gathering places. Physical and social relationships between primary houses and accompanying outbuildings. The value of live/work and gallery space within an urban fabric. How multiple building typologies attract diverse audiences, yet collectively contribute to a cohesive streetscape. And, above all, the advantages of locating every residence a few minutes’ walk from the essentials in a vital, engaging town center.

We interpreted Seaside’s architecture in the same manner, addressing design codes and the humanity behind them. Architecture that continued local and regional building traditions, providing connections with previous generations of a place. The dual role of the front porches as comfortable outdoor rooms and key elements in a welcoming streetscape. Cottages raised above grade with cross ventilation and deep roof overhangs to help cool them in the summer heat. The meaningful proportions and timelessness of Classicism, by itself and combined proportionally within simple vernacular structures. Interiors that stylistically stepped beyond old Florida cottages of earlier times, while maintaining their underlying spirit. That building materials could display the same type of integrity we admire in people. Carriage and guest houses providing opportunities for diverse and affordable housing. How towers contribute to our egalitarian natures by allowing every cottage to reach for views of the sea.

The reincarnation of Oedipus and Beauty and the Beast, stands at the corner of 42nd Street and 5th Avenue, waiting for the light to change.

—Joseph Campbell

Over the years, observing guests and visitors respond to the town convinced me that Seaside was no simple sum of planning and architecture. While the urbanism and design principles were substantive and meaningful, there was a compelling quality to the place transcending its design. Venturing around its edges, our visitors experienced it in much the same way as I had during those first forays—art films on the beachfront, magical afternoons in the Grill, the attention to detail of the founders and those who worked there, early events and gatherings at the Perspicacity Market, the unerring eye for quality and style displayed so simply—all collectively providing the beginnings of a de facto culture of Seaside.

An element of culture has been described in certain sociological and ethnological circles as ethos, or “emotional communality or ‘ambience’ that a group shares” and “a disposition…or attitude peculiar to a specific…group that distinguishes it from other groups.” Over time, I observed elements of an ethos of Seaside, distinguishing the town from our competitors as powerfully and profoundly as its design. For example, it was considered inappropriate to flaunt wealth or position. Disputes should be handled directly rather than through the courts. There was luxury in spending time by the sea doing nothing at all. A beach cottage could pass more on to the generations than real estate. A pursuit of quality and style could be both enjoyable and profitable. The world was rushing about madly and we refused to participate. Arts and humanities energize a small town. Sophistication and simplicity can exist hand in hand. While perhaps slow in execution, that same attention to detail can be worth the wait. It is possible to have a good time and do good work simultaneously. A business can be profitable for other reasons than filling up a checkbook.

To say elements of this underlying culture within Seaside were created according to some predetermined formula would be misleading, egocentric and dangerous. Rather, it developed quietly, slowly, and at times beneath immediate consciousness. A small town culture historically is shaped in part by the citizens who live there and interact daily. Yet, because of Seaside’s infancy and the predominance of second homes, few lived there full-time except the founders, Robert and Daryl Davis, whose contributions in this regard were nothing short of immeasurable. They were joined by employees, staff, architects, planners and outside contractors who collectively acted as torchbearers of the town’s worldview. This collection of special people became true citizens of Seaside (its forebears if you will) carrying with them the intensity and personal eccentricities normally belonging to residents. We were all expatriates of a sort. All perhaps disenchanted with typical approaches to our given areas of expertise. All, knowingly and unknowingly, played a part in shaping the culture of early Seaside.

Effectively presenting this culture (what little we discerned at the time) in a sales office presented a dilemma. Words were presumptuous. Authenticity seemed best conveyed through direct experience. Placing our own personalities aside, we cautiously began to allow the idea of Seaside to speak for us. Early visitors and prospective purchasers to our Tupelo Street cottage were treated as honored guests in our home in a small town. As they approached, no one greeted them while they were on the porch. Many times, they would hesitate there and, for a moment, absorb the calm surroundings of this exterior gallery. Unlike their suburban patio at home, our porches were simple, austere and complete outdoor rooms. We personally lived and worked on them daily. Toys were out for the children. An inviting swing and wicker chairs beckoned to them to sit awhile. They heard the Gulf, couldn’t see it, yet felt the constant beach breeze. Their immediate relationship with the sea from that porch across the street from it seemed more intimate than from a 9th floor condominium looking directly at it. For a moment, they glimpsed a central theme of Seaside, the luxury of spending an afternoon on the porch doing simply nothing. Unable to voice their feelings upon experiencing the dichotomy of that simple quiet cottage a short walk from the raw energy and vibrancy of the Grill, they would simply say they felt differently when they visited Seaside than anywhere else. An Asian sage might say we spoke without speaking. That the silent Seaside porch roared like a lion. Thus began the process of selling without selling.

That modest Tupelo Street cottage was just a short walk from more humble yet mindful beginnings of a small town. Streets that embraced them as pedestrians, scheduled and unscheduled gatherings, time well spent in the Grill, an outdoor film or concert, interactions with engaged and engaging characters, an hour or two shopping in the outdoor market, seeing their kids experience a certain freedom unknown at home. Collective experiences that eclipsed any attempts at “selling”, and, at times, verbal description at all. Expressed in this way, beyond words, the idea of Seaside suggested itself silently and subtly. Our role was shifting from “selling” to acting as guides and interpreters of the physical and cultural elements of place. We were beginning to transcend real estate.

And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

—T.S. Eliot

Somewhere in the midst of leading real estate sales in Seaside, I was struck by a startling personal realization. Gradually, often unnoticed, those two old worlds— business and art—fractured from one another since my leaving music, were becoming reconciled.

I continued to make a living with Seaside’s successful sales operations, leading the completion of a nationally and internationally recognized new town that would become a prototype for a powerful new approach to real estate development. However, this making a living was now sustained by a presentation and sales process approaching art—distilling and illustrating the intricacies of a new order of planning and architecture, then stepping beyond physical proportions to cautiously examine its human dimensions. My earlier reading and study, previously only a personal pursuit of knowledge and collective wisdom for its own sake, was becoming inextricably connected with an occupation. An act of performance—presentation of a community both physically and culturally—became a means to a most satisfying end— meaningful placemaking. Throughout it all, providing one voice within a collection of creative and engaged people pursuing this nuanced work again revived those transcendent moments from ensemble music.

Since those early Seaside years, I have consulted in over sixty new and existing communities regionally, nationally and internationally. It remains a rarified place, this shaping of real estate, physically and culturally, within the framework of its development, marketing and sales. Seaside’s role in this journey was both a beginning, and a return. A place where an admixture of special people, ideas and circumstances constellated in one place at one time. An opportunity for its completion to contribute to my own. Few who got so close remained untouched.

To create transcendent place requires no less than transcendence on the part of those who are participants. There can be no other way.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE