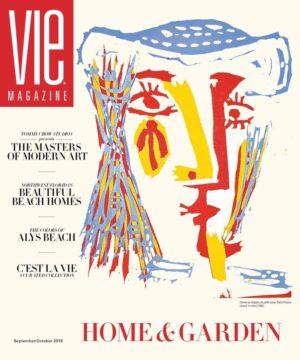

vie-magazine-tommy-crow

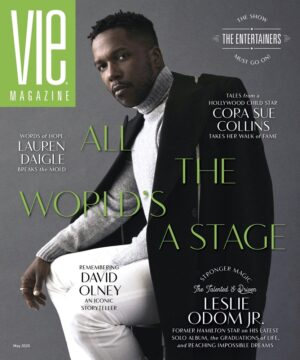

Rediscovering Crow

The Cuban Influence on the Passion of Tommy Crow

By Stephanie Morris-Crow | Photography by Tommy Crow

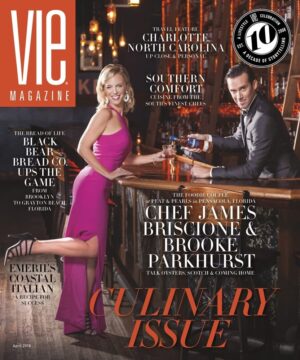

Our March 2013 trip to Cuba was booked, and it was one of those strange coincidences in life that led to photographer Tommy Crow’s exciting recent project. The Pearl, a boutique luxury hotel in Rosemary Beach, Florida, was set to open this summer and feature, of all things, a Cuban-themed restaurant. And, since we were already going, they asked if maybe some of our trip photographs would work for the hotel. This collaboration has led to one of the most intensive and creative six months of Tommy’s life. Our trip to Cuba inspired an entire new art series, but it also changed our whole perspective on everything we’d ever heard about Cuba.

It began on a Monday afternoon as our filled-to-capacity Delta charter plane touched down on a worn asphalt runway surrounded by grassy fields. Earlier, during the hour-long flight from Miami to Havana, a passenger asked the flight attendant what she thought about Cuba. “Oh, they don’t let us off the plane,” she replied. It’s not the Cuban officials who keep US flight crews from disembarking, but rather the United States government—a clear example of the uneasy relationship between our country and the closest socialist government to our shores.

Citizens of the United States are legally allowed to travel to Cuba, but only on licensed trips involving cultural, educational, or humanitarian exchanges. These trips are made possible through a handful of tour operators granted “people-to-people” licenses by the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). Through one of these tour operators, Tommy and I arranged our recent trip.

The Havana airport is small, with polished white tile floors and high ceilings. Passing through the customs portals, our documents were inspected by polite young women clad in militaristic olive-green uniforms: short-sleeved tops paired with tight-fitting skirts or long pants and sensible, flat-soled black shoes. It all seemed to be exactly what you’d expect to see in an airport of a communist country—until I noticed their legs. In contrast to the stark and efficient uniforms, each woman wore black patterned stockings. Each pair was different: some designs had flowers woven in, some had spiderweb patterns, and others had shooting stars. With our entry all approved, we passed through with no problems.

Pablo, our Cuban tour guide, greeted us in the baggage claim area. Wearing a straw fedora, he was tall with toast-brown skin and a thin, wiry body that was constantly moving. A former college history professor, Pablo is highly educated and fluent in several languages, and, according to our US-based tour company representative, he is reputed to be the best tour guide in all of Cuba. Like almost everything in Cuba, tourism is managed by an official government office—in this case, it’s the Ministry of Tourism. In many ways, Pablo acts as an ambassador for Cuba. He had just returned from Switzerland as part of a consortium on Cuban trade and political relations. Virtually every working-age Cuban is barred from travel outside of Cuba, while Pablo is allowed to leave the country as he wishes—a special privilege afforded to him as a government employee. Shaking hands with people, pointing, and smiling, he gently herded the forty members of our tour group single file out the door.

The bus was comfortably plush and air-conditioned. Pablo positioned himself at the front of the bus with microphone in hand. As we slowly eased out of the small parking lot, he began: “As a socialist society, we don’t really allow advertising, such as you do in the States as a capitalist society. All billboards that you will see, they are government slogans and propaganda.” Looking out the bus windows, it was impossible to see anything but roadside billboards. Views of adjacent fields and plantain groves were mostly blocked by panels of smiling cartoon characters and slogans. Translated, they say such things as “Long Live the Revolution,” “Thank you, Che, for Socialism,” or just simply “Thank you, Che!” Che Guevara, Pablo told us, is the national hero and idolized symbol for Cuban communism. He is so firmly entrenched in Cuban nationalism, it is impossible to separate “El Che” the man from the Cuban socialist dream of promise.

Before our hotel check-in, the tour bus had one absolutely nonnegotiable, government-mandated stop—Revolution Square in Havana. The main focal point of the square is the José Martí Memorial, an enormous tower standing at three hundred fifty-eight feet. Looming across the vast square, it faces a pair of government office buildings supporting a gigantic mural of Che Guevara. The real purpose of this stop, it seemed to me, was for a quiet show of power—a subtle reminder of who’s really in charge here.

The square, Pablo told us, is home to all major political rallies in Cuba. From an elevated podium, leaders including Fidel Castro, his brother Raúl, and other notables (such as Pope Benedict during a visit in 2012) have addressed the people. Attendance of political rallies is mandatory for Cuban citizens. “Sometimes this is a problem,” said Pablo, “for, when [Fidel] Castro would give a speech, he talked for hours, just on and on and on.”

Our mandatory thirty minutes at the square ended and we boarded the bus to our hotel, the Spanish-owned, five-star Meliá Cohiba. Upon entering the lobby, I was at once enthralled by the beautiful polished stone floors, the dark wood-paneled walls, the elegant artwork, the grand piano, and the faintest wisps of cigar smoke perfuming the air. None of the poverty or political backwardness that we Americans ascribe to Cuba was apparent.

After helping Tommy bring our bags into the hotel room, I scurried back toward the door. “Hey! Where are you going?” Tommy called after me. I assumed he was perturbed by my willingness to toss the bags and go. But in reality, he was very concerned with the fact that we were in a communist country. I had fewer concerns; after all, Canadians have been vacationing in Cuba for the past fifty years. I was sure we would be fine. “I’m going to have my very first Cuba libre—in actual Cuba—so hurry up,” I called back. Downstairs, I sat at the round lobby bar, enjoying its polished brass, dark wood, and view of the blue ocean through floor-to-ceiling windows.

The hotel faces the Malecón, a four-mile-long seawall and roadway that hugs the rocky Havana shoreline. On any given day of the week, Cuban lovers can be seen walking hand in hand along the esplanade or sitting on the wall gazing at the ocean waves. For over a century, it has been popular with locals, both young and old, for daily socializing and relaxing. That day, clear but windy, the waves crashed against the seawall, sending white splashes of foam forty feet into the air. I watched the 1950s-era cars, painted bright candy colors, cruise up and down the highway. These cars, amazingly still driving around and privately owned, are employed as taxis. “Cuba,” Pablo told us, “has the best mechanics in the world.”

On any given day of the week, Cuban lovers can be seen walking hand in hand along the esplanade or sitting on the wall gazing at the ocean waves.

I asked the bartender about rum varieties; she suggested the local brand, Havana Club Rum. It has good quality and smoothness, and, as it became apparent throughout our stay, Havana Club Rum is the rum of choice offered by every bar and restaurant that caters to tourists—which is virtually all of them. Havana Club Rum is actually a private company in which the Cuban government has a 50 percent stake. Even with the government’s involvement, it’s still great rum and it beats the pants off Bacardi.

As for my Cuba libre? Its murky historical origins notwithstanding, everyone agrees this cocktail was first mixed in Cuba. The ingredients are simple: white rum, Coca-Cola, and a squeeze of lime. Even with the US embargo and restrictions on US companies selling, supplying, or bartering anything to Cuba, my drink was mixed with real Coca-Cola. I inspected the soda can: this particular can of soda was produced and distributed via Mexico. Tommy joined me, asking, “Well, does a Cuba libre taste better in Cuba?” Yes, I replied. In fact, I decided to have one more.

That night, we heard our first cannon boom from the city’s historical fort, Castillo de San Carlos de la Cabaña, or simply La Cabaña. A nightly ritual, it announces the onset of evening at nine. La Cabaña, the third largest fortress complex in the Americas, now serves as a historical park and houses several public museums. By the time the cannon booms, the Malecón has already filled with teenagers, families, and lovers, all strolling along the seaside beneath a velvety, starlit sky.

I asked the bartender about rum varieties; she suggested the local brand, Havana Club Rum. It has good quality and smoothness, and, as it became apparent throughout our stay, Havana Club Rum is the rum of choice offered by every bar and restaurant that caters to tourists—which is virtually all of them. Havana Club Rum is actually a private company in which the Cuban government has a 50 percent stake. Even with the government’s involvement, it’s still great rum and it beats the pants off Bacardi.

As for my Cuba libre? Its murky historical origins notwithstanding, everyone agrees this cocktail was first mixed in Cuba. The ingredients are simple: white rum, Coca-Cola, and a squeeze of lime. Even with the US embargo and restrictions on US companies selling, supplying, or bartering anything to Cuba, my drink was mixed with real Coca-Cola. I inspected the soda can: this particular can of soda was produced and distributed via Mexico. Tommy joined me, asking, “Well, does a Cuba libre taste better in Cuba?” Yes, I replied. In fact, I decided to have one more.

That night, we heard our first cannon boom from the city’s historical fort, Castillo de San Carlos de la Cabaña, or simply La Cabaña. A nightly ritual, it announces the onset of evening at nine. La Cabaña, the third largest fortress complex in the Americas, now serves as a historical park and houses several public museums. By the time the cannon booms, the Malecón has already filled with teenagers, families, and lovers, all strolling along the seaside beneath a velvety, starlit sky.

Even with such poverty, the crime rate in Cuba is very low. Once, while touring historical downtown Havana with the group, I became separated and was lost for several hours. I wandered alone through the side streets and alleyways toting one of Tommy’s huge and obviously very expensive cameras. If ever there was a golden opportunity for someone to mug me, that probably would’ve been the time. But everyone in the busy street responded to me in a friendly manner, politely going about their own business. Danny, the private tour guide that we hired later in the week, explained the reason for the low crime. “It’s because you never know who is watching,” he said, with a gesture that implied possible hidden cameras. He told us there were still plain-clothed government officials among the population, keeping tabs on everyone. Clearly, Castro had learned a thing or two from the former KGB.

Late on Wednesday evening, Tommy arranged to go out with Danny. They were going to search for a very specific shot to photograph: a beautiful woman dancing—a real spirited and fiery cubanita. Sadly, I wasn’t going with them. I was one of five from our tour group to come down with a horrible upper respiratory virus and was sick in bed. I weakly wished Tommy luck and stayed in the hotel room, watching government propaganda on TV.

Unfortunately for Tommy, nightclubs would not allow photographers, or at least not ones with professional cameras. “Prostitutes,” he was told. “No pictures.” Tommy returned to the hotel in an hour or so, disappointed. Danny later elaborated that the “hottest” bars and dance clubs were full of prostitutes, male and female. They did not allow photographs of themselves or their clients. Tommy did tell me that, from the outside, you wouldn’t have been able to tell the places apart from any hot dance club or bar in Los Angeles or New York.

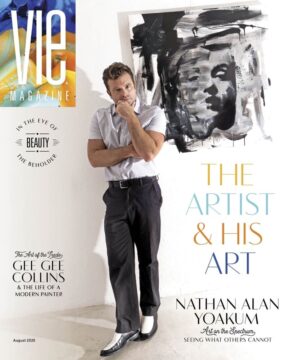

The following day, during a bus tour, his camera finger clicking away, Tommy kept repeating, “There’s not enough time. We need to come back soon. There’s so much that I’m not getting.” Tommy’s interest in photography and Cuba are interwoven through the influences of two fathers. His passion for photography sprang from his birth father, Major Thomas P. Ingrassia. Ingrassia was a jet pilot in the US Air Force and a photography enthusiast. Tommy’s first interest in Havana came from stories about the beautiful scenery and architecture as told by his adoptive father, Alva Crow. Alva, before marrying Tommy’s mother, would routinely hop on a plane and go from South Georgia to Havana for long weekends of carousing with his buddies. Back in the early fifties, this kind of junket was much like today’s weekend getaway to Vegas.

Our tour bus was now driving past a stately memorial park, flanked on both sides by foreign embassies, including North Korea’s. “Don’t forget,” Pablo lectured, “it’s the victors who write the history books. Here in Cuba, the Bay of Pigs invasion was a huge victory for us, for the Revolution. From our point of view, we had defeated the United States in battle.” During the invasion, Cuban pilots retained total control of the air. Their decisive victory was aided, in great part, by flying the technologically advanced T-33 jet. These jets, American-produced by Lockheed, were leftovers from Cuban dictator Batista’s then US-friendly Cuban Air Force. But commandeered by Castro’s rebels and flown by trained Cuban pilots loyal to the Revolution, they proved to be more powerful than the US B-26s.

One year after the Bay of Pigs, Major Ingrassia was training in the same aircraft that was the key to Cuba’s victory. Flying over Arizona, the engine of the T-33 failed. Tragically, he did not survive the landing. Tommy, my husband, was only five years old at the time. Years later, after his mother remarried, his new, adoptive father, Crow, enjoyed regaling Tommy and his sisters with stories of Havana’s excitement and beauty.

Tommy’s first photographs were taken with Major Ingrassia’s old camera. “It took me forever to figure out f-stops and apertures,” he says fondly. He continued taking photos throughout high school, after which he planned to follow in his birth father’s footsteps and become a jet pilot. To his great disappointment, flight school requirements included perfect vision. Having had glasses since the age of seven, Tommy was forced to reexamine his future path. He decided to attend college at the University of Georgia, his adoptive father’s alma mater.

Now, when I see his “double wing” logo adorning studio T-shirts and various objects related to his photography business, I’m reminded of the facts. The logo is a near replica of his birth father’s pilot wings, topped with his adopted father’s (now Tommy’s) surname. His two identities are merged in this image. When asked about the connection and whether it was intentional, Tommy becomes contemplative. “You know, sometimes the things that you create, you’re not aware of why you create them, you just keep going until it feels right.” It’s strange, really, how Cuba has intertwined with the facts of his life—even before he was commissioned for The Pearl’s artwork.

On our last day in Havana, Danny drove us to a farmers’ market located far off the main drag in an old art deco warehouse. It was not a tourist attraction; it was simply the Cuban version of a grocery store. Freshly butchered meat was laid out on scrubbed wooden tables. Carrots were piled high; some of the dirt from which they were pulled was still clinging to them. They even had flowers for sale, single blooms or bouquets. Surprisingly, for an open-air market, there were no unpleasant odors or swarming flies. In Havana, even amid the poverty, the friendly smiles from the locals were genuine. One of Danny’s friends passed by; he was carrying a turtle and nodded a friendly hello. “It’s like his dog,” Danny explained.

Based on the Cuban example, happiness or joy of life isn’t a result of having wealth. It’s an appreciation for whatever you have and the love that’s available to you. Cubans lack access to products that we Americans take for granted—clothing, electronics, and simple building materials like concrete—yet they take extreme pride in their homeland and personal belongings. While lost and wandering the side streets in Old Havana, I saw men and women, private citizens, wiping windows, adding a new layer of paint to the crumbling walls of their buildings, sweeping streets and sidewalks spotlessly clean. Everyone’s colorful clothing, though a bit worn, was in good repair. I saw almost no one in rags or dressed with sloppy attention to their appearance.

Based on the Cuban example, happiness or joy of life isn’t a result of having wealth. It’s an appreciation for whatever you have and the love that’s available to you.

I say “almost” because we did meet a couple of ragged and dirty elderly men: winos by the looks of them. Tommy asked to take their photos and after smiling for a few snaps, Tommy gave them five pesos. They smiled, jumped up, and excitedly ran away down the sidewalk. Danny asked how much Tommy gave them, and when told, he nearly choked. “Those two are going to be drunk for a month off of that!”

Cuba, a beautiful island with a complex history, has certainly been one of the most interesting and intriguing places I’ve ever visited. Full of beauty, mystery, and charm, it should find a home on anyone’s bucket list. Full of educated citizens, the way in which Cuba develops her economic strength in the future may well have an impact on our own country. Pablo and Danny both expressed the Cuban perspective in this way: “Our governments don’t get along, but we like Americans just fine.” I feel exactly the same way about Cuba and I hope our two governments will eventually find political friendship in order for more people to have life-changing experiences there as Tommy and I did.

— V —

Tommy’s new Cuban photography series is now hanging throughout The Pearl’s lobby and restaurant in Rosemary Beach, Florida. Art pieces from his earlier series are in corridors and guest rooms. Beauty, composition, and depth of perspective, all informed by his three decades as an advertising photographer, are evident. In the photographs are many of the people we met, their spirits and joyfulness beaming through in every image. However, you won’t see images of Pablo or Danny. In fact, those aren’t even their real names. I’m not sure of the Cuban government’s reactions to even slight criticisms by their citizens, so just in case, their identities will remain secret.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE