vie-magazine-shaya-new-orleans-chef-hero-min

The interior of Saba, Chef Alon Shaya’s restaurant in New Orleans | Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

Recipes for Remembrance

Chef Honors Holocaust Victims and Survivors

By Anthea Gerrie

It was a turkey, but not as we know it. The meat had been stripped off the bird, ground by hand, seasoned, spiced, and repacked onto the bone in a traditional turkey shape, giving no clue to the delicious alchemy hidden within.

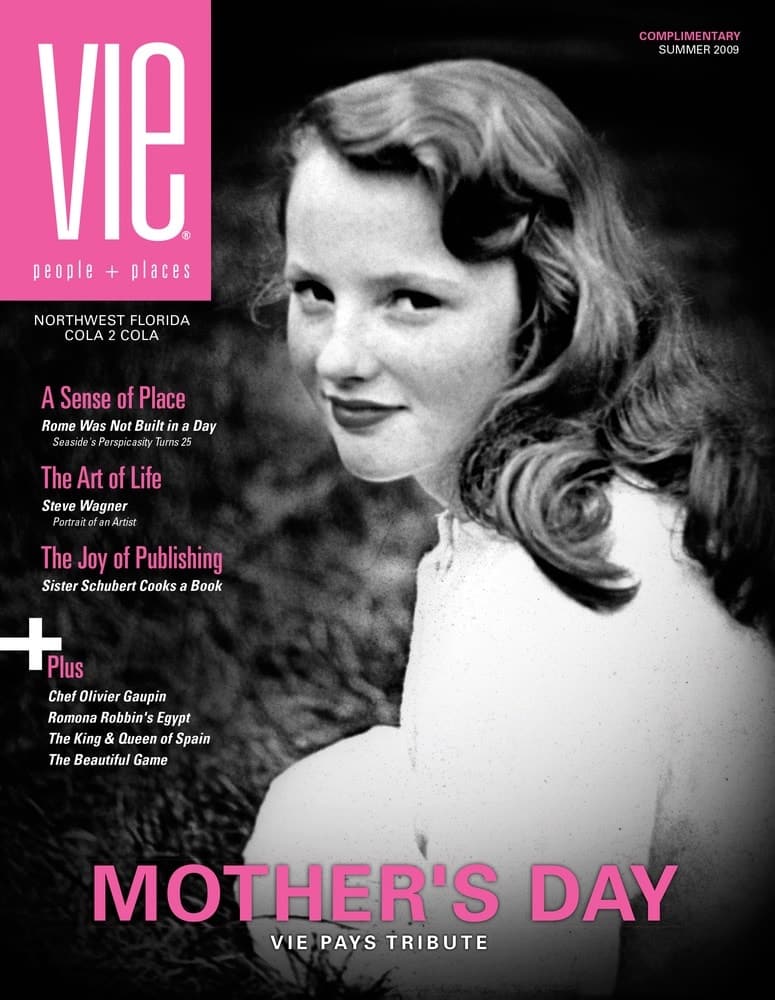

Some might find such exotic treatment of a hallowed holiday bird an unwelcome surprise, but not Steven Fenves (formerly Fenyves). He lifted it with trembling anticipation from the delivery box in which it had been dispatched from New Orleans by award-winning chef Alon Shaya. For what lay within was, Steven admits, nothing less than the taste of his childhood—a world he had left behind seventy-five years ago.

- Semolina sticks, one of the recipes Chef Shaya resurrected from a cookbook written by Holocaust victim Klara Fenyves | Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

- Chef Alon Shaya’s re-creation of the Fenyves family’s turkey recipe, one of Steven’s favorites | Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

- Another variation of Klara’s semolina sticks recipe | Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

- Potato circles, another of Klara Fenyves’s recipes saved in her family cookbook and remade by Chef Shaya | Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

“It was an east European family favorite I never expected to eat again,” explains the Holocaust survivor whose mother, Klara, was the creator of the recipe. She died in Auschwitz in 1944. “It brought back memories of a rich, intense life full of celebrations I never expected to relive.”

Such was the power of the family recipe book that Steven and his sister, Eszti, never imagined would have survived the war when they returned from the concentration camps to Subotica in the former Yugoslavia, a town from which they were so brutally deported in 1944.

“Our neighbors knew it was about to happen and lined up on the stairs to loot our possessions as soon as we left,” says the 89-year-old, a retired professor of computer science who now lives in Maryland. “But they didn’t reckon with Maris.”

Maris was the family cook who over the years had faithfully re-created Klara’s handwritten recipes, many inspired by her mother, aunt, and sister-in-law. The loyal servant had been let go three years earlier along with the governess, the maid, and the gardener. Still, when Hungarian occupying officers commandeered the Fenyves apartment and made the family crowd into one tiny corner, Maris was ready and waiting outside to help save whatever she could of their possessions. Police came to evict the family as part of a purge of the town’s six thousand Jews, leading them past neighbors who cursed and spat on them as they left. The looters waited to pounce on all that the family was forced to leave behind.

Except one.

- Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

- Steven Fenves, Holocaust survivor and former professor at the University of Illinois | Photo courtesy of Steven Fenves

“Maris competed with the crowd jostling to ransack our apartment, dived in, and saved the recipe book, a diary our mother kept of Eszti’s and my early development, and a cardboard binder into which she stuffed all our mother’s lithographs, etchings, and sketchbooks,” says Steven. He has Klara’s beautiful framed artwork as a backdrop behind him as we speak.

The images, the recipes, and even a sofa—with a hand-stitched cover embroidered by Klara and her mother—all survived their creator, thanks to Maris. Klara was murdered soon after arriving at the death camp with her children. At only thirteen years old, Steven last saw her in the selection line through which all prisoners passed on arrival. He only survived because of his fluency in languages; he grew up speaking Serbian in school, Hungarian at home, and German with his governess. These skills made him valuable as an interpreter. Joining a resistance cell set up in the neighboring camp of Birkenau, he was even able to smuggle a bartered scarf and a sweater to his sister as she clung to survival.

After surviving a death march to Buchenwald, Steven was liberated by the Americans and repatriated four months later to Subotica. There he reunited with Eszti and their father, Louis, who had spent the years since their separation in a coal mine. Broken in body and spirit, Louis died a few months after being reunited with his children.

The universal pastime was getting together in groups, talking about foods you had eaten, and making up stories of the meals you were going to order when you got out.

In a rare and unexpected moment of brightness during this bleak period, Maris came back into the orphans’ lives bearing tangible testaments to their mother’s creative spirit. “It was a wonderful surprise to see all the beautiful artwork again that we thought was gone forever,” says Steven, whose lip trembles as he remembers the savior of this family treasure. But realizing there was nothing to keep them in Subotica after their father died, he and Eszti soon had to consign the precious folder back to Maris for safekeeping. They donated the sofa to the town museum and fled Yugoslavia for western Europe with only a small suitcase apiece.

“Finally, in 1963, Maris obtained permission to send the folder to us in Chicago, where in 1950 we came to live with our maternal uncle,” says Steven. He studied civil engineering at the University of Illinois, where he later became a professor.

“We put up the artwork but, although one of Eszti’s four daughters learned to make a couple of my mother’s dishes, it would be many years before I would get the chance to taste any more from the collection of recipes that were in our past.”

Eszti lent the recipe book to an exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, which holds artifacts from thousands of victims. When his sister died in 2012, Steven donated the book to the museum. It would be another seven years before any of the recipes would be brought to life by a chef who viewed them in the archives and was moved to action.

- Steven Fenves and his sister, Estera (above), survived the Holocaust after spending months in concentration camps. Their parents, Klara and Louis, did not survive. Klara was killed at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Louis was liberated from a work camp only to die a few months later. | Photo from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Steven Fenves

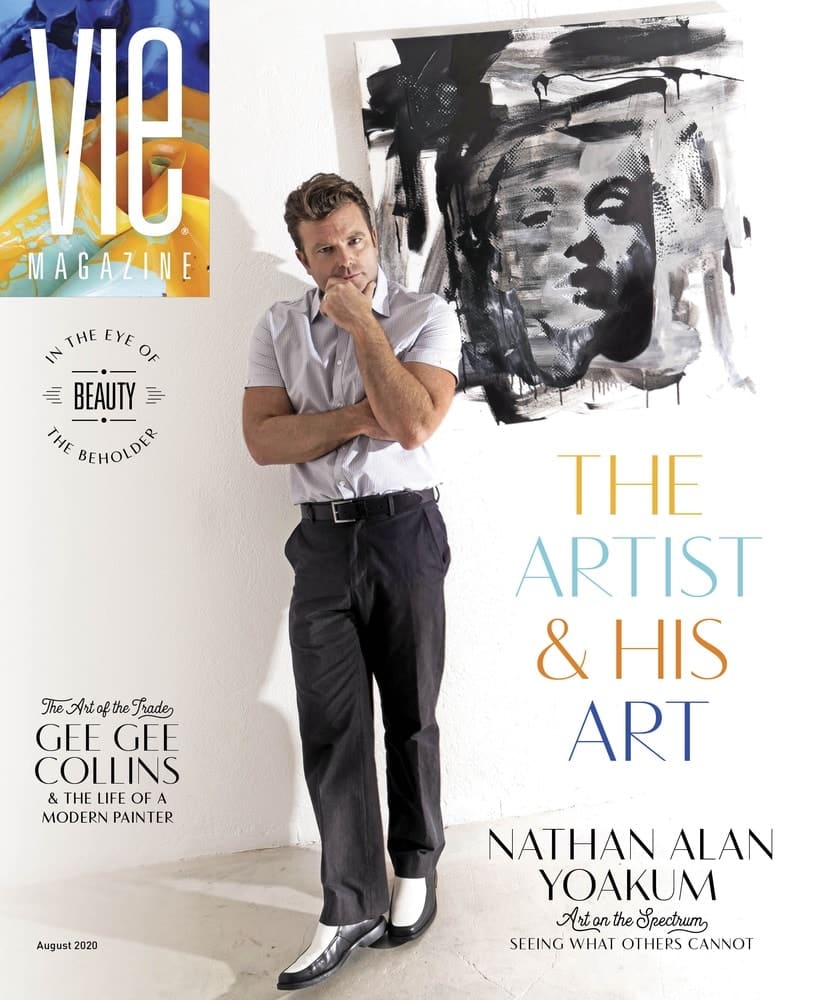

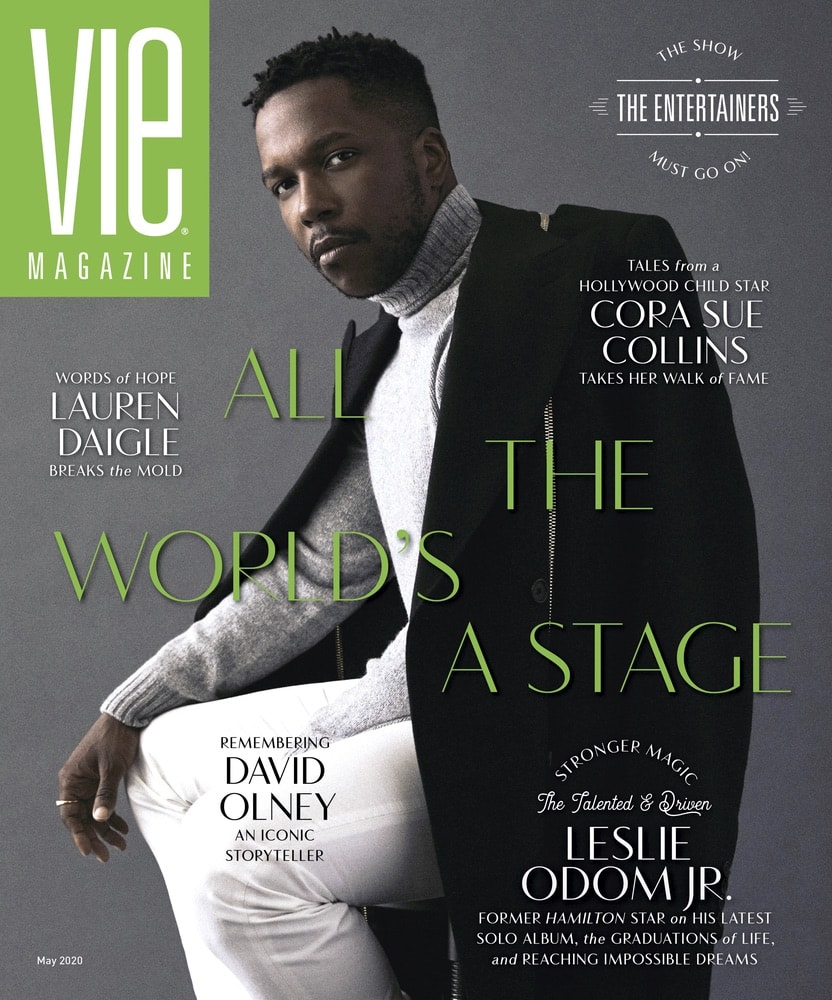

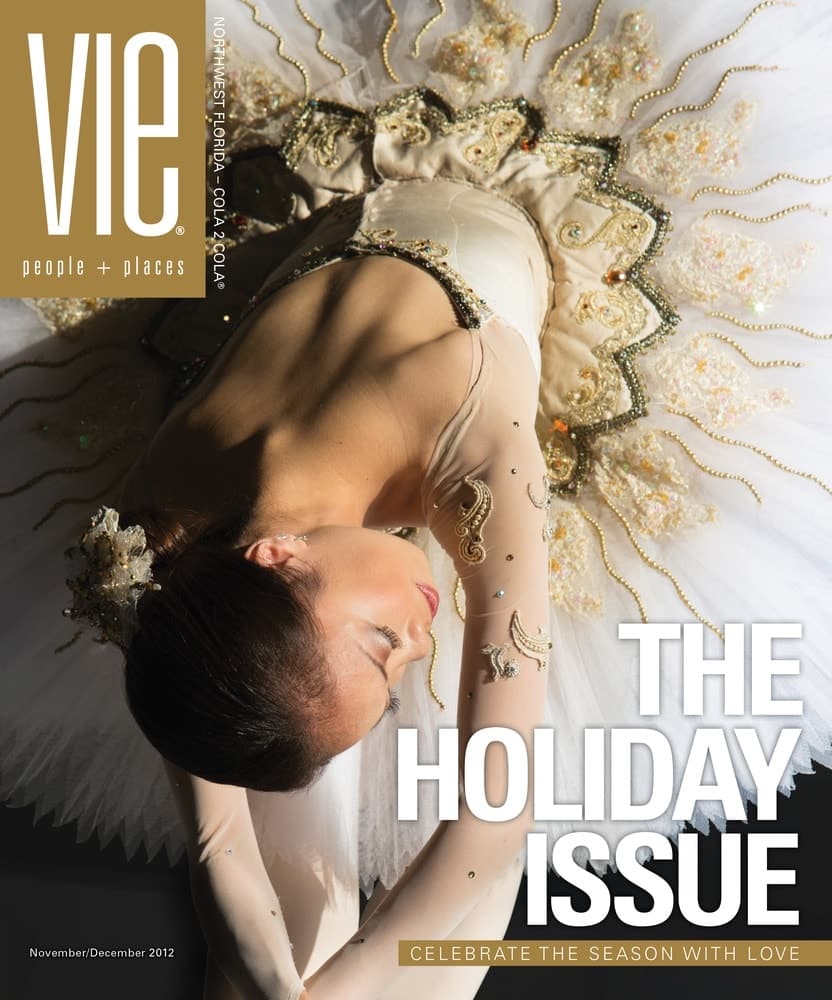

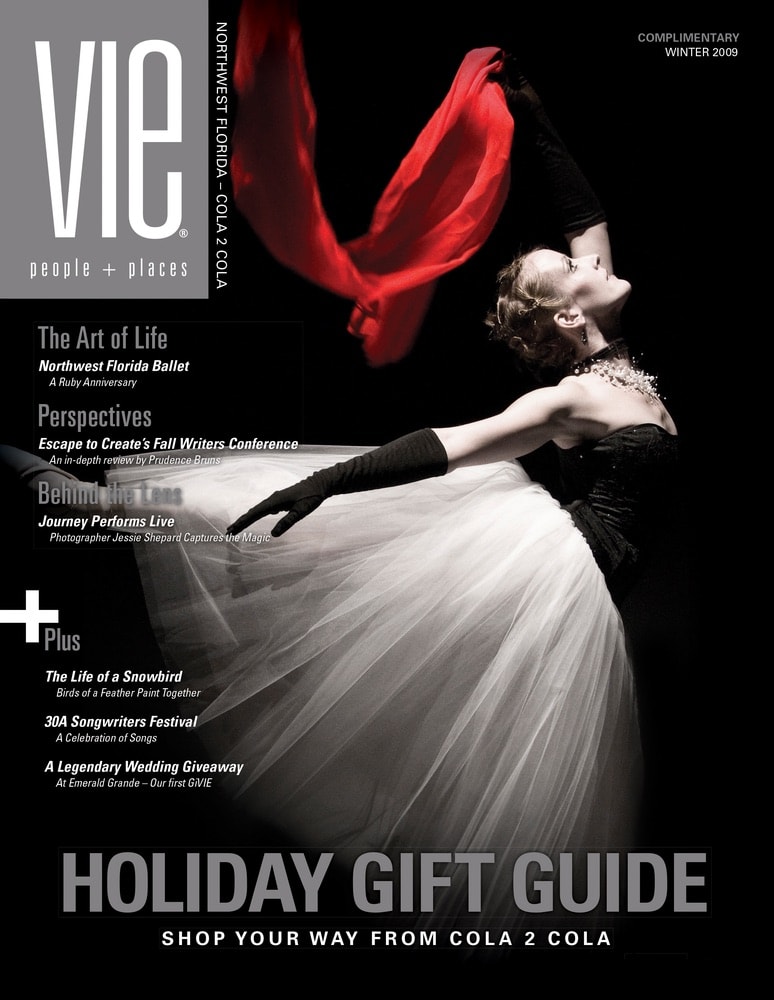

- Chef Alon Shaya at his popular restaurant, Saba, in New Orleans | Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

“Having dedicated my life to storytelling through food, I felt it was so important to tell the stories of these dishes,” says Alon Shaya.

The chef—whose first New Orleans eatery, Shaya, was named Best New Restaurant in the 2016 James Beard Awards—already had a special place in his heart for the recipes Holocaust victims scribbled even as they were starving in concentration camps. He viewed the first at Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, during a culinary tour of Israel. In the DC museum, he saw others that had been preserved for posterity by prisoner Ilona Kellner. “She smuggled scraps of paper from the office where she worked to other prisoners to preserve the food memories of these women,” says Alon, whose grandfather was a victim of Nazi persecution in Hungary. “They wanted to discuss the dishes they loved and write down how to make them even though they were starving.”

Steven confirms the prisoners’ food obsession from his memories of Auschwitz. “I lived in a block where you stayed until you died of starvation, and the universal pastime was getting together in groups, talking about foods you had eaten, and making up stories of the meals you were going to order when you got out,” he says.

“Cooking this food with Steven’s feedback is one of the most important things I’ve ever done, and it helped me remember why I began cooking in the first place.”

Alon never expected he would get the chance to bring some of those victims’ recipes to life. “Most of their authors were long gone,” he says. “When I found the Fenyves family cookbook and learned Steven was still alive and volunteering at the museum, I realized he was a living link to the dishes, someone I could talk to directly about how they should taste.”

And so began a long correspondence that led to Steven’s selecting a dozen recipes from the slender, food-stained volume of more than 140—numerous appetizers, salads, cakes, and pastries and just a few cursory meat dishes. He translated them for Alon to cook, and the chef sent Steven the food for evaluation. It was nothing less than a labor of love for the chef and not an easy exercise, he confesses. “There were few measurements in the recipes and no description of techniques. It was more like ‘cut up some onions and fry them in a pan.’” Alon was helped by the shared heritage of Klara, who had studied in Budapest, and his own Bulgarian grandmother. “I had gotten to cook some of my grandmother’s recipes and thought back to how she prepared things as they did in eastern Europe.”

Gradually, Alon started re-creating dishes that spoke to Steven more than any others of his happy childhood. In addition to the turkey, the semolina sticks were a favorite side dish at the Fenyves table. The yeasted potato circles stuffed with ground beef were served to guests on special occasions, as were the walnut and poppy seed pastries and frosted cakes. One of those, richly flavored with walnuts, Alon presented in an online event staged by the museum. For this, a meat grinder was essential; both men recalled growing up in family kitchens where such an implement took pride of place. In the Fenyves household, it was used for hand grinding the copious local harvests of walnuts and hazelnuts as well as meat.

Steven Fenves and his sister, Estera, survived the Holocaust after spending months in concentration camps. Their parents (above), Klara and Louis, did not survive. Klara was killed at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Louis was liberated from a work camp only to die a few months later. | Photo from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Steven Fenves

Now the recipes are set to begin a new life as Alon starts showcasing them when his restaurants fully reopen. “I see putting on the potato circles as a sharing appetizer and re-creating the ground turkey as a kebab or an individual serving of Cornish hen,” he muses. “The semolina sticks would also make a great appetizer, and diners will love the walnut and poppy seed horseshoes.”

Waitstaff will tell the story of the dishes, which Steven hopes to be among the first to try in the restaurant. “I’m looking forward to getting to New Orleans with my wife and meeting up there with my son and daughter-in-law who live in Atlanta,” says the father of four who has been married to Norma for sixty-five years.

While Steven is keen to sample the Israeli-influenced dishes Alon is famous for at Saba, the chef’s ambition is to re-create more of the memory-evoking recipes Holocaust survivors may have thought were gone forever. “I am planning a fund-raiser once dining is fully open, to get more of these recipes translated,” he explains.

“Cooking this food with Steven’s feedback is one of the most important things I’ve ever done, and it helped me remember why I began cooking in the first place,” Alon adds. “I look for stories and meaning in the dishes I cook, and I’ve waited my entire career to be able to share memories in my bid to bring joy and happiness to people through food.”

Donations to the museum’s recipe translation effort can be made via USHMM.org/recipes. Learn more about Alon Shaya and his restaurants at PomHospitality.com and EatwithSaba.com.

Photo courtesy of Alon Shaya

Alon Shaya’s Walnut Cake

Inspired by the memories of Steven Fenves

Yields one nine-by-five-inch loaf cake

Ingredients

8 large eggs, separated

1 teaspoon cream of tartar

2 teaspoons kosher salt

1 1/4 cups granulated sugar

Zest of 2 lemons

2 cups dark chocolate chips or pieces

5 cups walnut pieces

3/4 cup almond flour

1 cup whole milk

12 ounces soft unsalted butter

1 1/2 powdered sugar

3/4 teaspoon vanilla extract

Directions

Preheat oven to 300°F and toast walnut pieces for 15 minutes or until golden brown. Remove from oven, let cool, reserve 1/2 cup for garnish, and grind the remaining nuts through a meat grinder or chop in a food processor.

Line a 9-by-5-inch loaf pan with buttered parchment and turn the oven heat up to 350 degrees. Whip egg whites with cream of tartar to form stiff peaks, then incorporate 1 teaspoon of the salt. Whisk egg yolks in a separate bowl with 1/2 cup of the granulated sugar and the zest of one lemon till light and fluffy.

Melt 1 cup of the chocolate and pour into the whipped yolk mixture, whisking well. Fold in 1 cup of the ground walnuts and the almond flour, then when well combined, carefully fold in 1/3 of the whipped egg whites. Repeat twice more, and once fully incorporated, pour batter into the loaf pan and bake 40 to 45 minutes until a skewer comes out clean.

Let cool 15 minutes in the pan, then remove and continue cooling on a wire rack. Slice lengthwise into thirds and layer with filling made by heating 2 cups ground walnuts with the milk and 3/4 cup of granulated sugar, simmered together for 10 minutes. Remove from heat and stir in remaining chocolate, combine and cool to room temperature.

To ice the layered cake after chilling in the refrigerator for two hours, whisk the butter on high speed with the powdered sugar, vanilla, remaining cup ground walnuts, zest of remaining lemon, and remaining teaspoon of salt until light and fluffy.

Garnish cake with toasted walnut halves and serve at room temperature.

— V —

<

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE