vie-magazine-steve-wagner-painting

Portrait of Artist Steve Wagner

By Sallie Boyles

With his charming smile and ready humor, artist Steve Wagner exudes the easygoing warmth of his Southern upbringing. He has reason to smile. Now that his children are grown and the pressures of his Atlanta graphic design business are history, Steve is living his dream in the good company of his wife, two dogs, and many friends. Indulging his passion to paint and sculpt, Steve fully appreciates the idyllic setting of his home and studio, which are close to the happenings of 30A, yet peacefully secluded. Even so, it would be wrong to assume that serious thought escapes such a man.

Scratch the surface and you will uncover a fascinating blend of passion and purpose, instinct and knowledge. Being an artist is part of Steve’s genetic makeup, but his technique is a result of lifelong study. “It’s in my bones,” he said. In fact, Steve takes after his artistically gifted mother, grandfather (who designed the original Mars candy packaging), and great-grandfather. Pure desire compelled him to draw as a child. “I believe any artist has to love drawing to continue creating,” said Steve. From the start, he also understood the value of study plus practice to refine his innate gift.

Since art classes did not exist in the schools of Newnan, Georgia, where he grew up, Steve took private lessons as boy. “I was fortunate to have teachers in Newnan like Tommy Powers, Tony Dykes and Lavonne Gault,” said Steve, who believes that children face a disadvantage when they are not exposed to the fine arts. Pointing to research that shows a correlation between creating and critical thinking, Steve soundly advocates instilling art curricula that cultivate problem-solving skills.

He also regrets that relatively few budding artists have the opportunity to develop their talents early on. Just as certain math and science requirements must be met in high school to prepare for college, a proper foundation is necessary if young artists hope to compete for spots in the fine arts colleges. “With the exception of cities like New York,” he said, “not many high schools around the country focus on the arts.”

[double_column_left]

Steve Wagner paints our photographer

Photo by Jessie Shepard

Steve’s other concern is that art students today are not learning the fundamentals. “Instructors are saying, ‘Paint what you like,’ to the point that their students never learn essential techniques,” he said. “They don’t know how to draw.” It’s inexcusable to Steve that a number of today’s artists don’t know how to prep a canvas or use a medium properly. As an example, he mentions a painting with an $8,000 price tag he saw in a Napa gallery. “It was a beautiful work, but the artist had painted it directly on raw linen. Anyone who understands the first thing about oil painting would know that oil in the paint will rot the linen.”

Always cognizant of the need for preparation, Steve went to college to pursue a career in graphic design. He spent the first two years taking basic art courses at the University of Georgia before transferring to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, for more serious study. At Pratt, art permeated the culture; it flowed from the classroom to the social scene, fostering an environment of enrichment—an atmosphere Steve wholeheartedly endorses. He completed his major in Visual Design at Auburn University and graduated with his BFA degree in 1970.

[/double_column_right]

Photo by Jessie Shepard

Before entering the world of commercial art, Steve played the bohemian backpacker, taking nine months to tour Europe—Spain, France, England, Greece. This journey was his opportunity to experience firsthand the Old World art and culture that he emulates in his work. He traveled solo, which Steve said was ideal for meeting people. Getting from place to place, he generally took a train or hitchhiked. When he needed money, he got a job. “I worked as a deckhand on a boat out of Cannes for eight weeks,” he said with satisfaction. He also lived in a cave in Crete. Visually and emotionally, the trip left a profound impression. “With the Viet Nam War just over and the Paris Peace Accords being negotiated, it was an intense time to be abroad.”

The “eye-opener” for Steve, however, was to be in the presence of the paintings and sculptures of the Old Masters. Above all, Amedeo Modigliani, well known for his portraits, nudes and sculpture, captivated Steve. “I’ve always loved the work of Modigliani,” said Steve. “His muse has been mine from the beginning.” That influence is most apparent in Steve’s stone sculpture but also in his nude painting.

While Steve categorizes his work as realistic, many of his paintings follow the French Impressionists’ technique. The foaming waves in his seascapes are an example. “If you want realism, you should take a photograph of the ocean,” he offers. He prefers an impressionistic interpretation to convey the emotion.

Photo by Jessie Shepard

Photo by Jessie Shepard

Another important influence on Steve’s art is Pointillism, a technique initiated by Georges Seurat, who was a leader among the 19th-century French Neo-Impressionists. The process plays one color against another with applications of tiny brushstrokes. In Roman Road, an impressive 48 x 60 oil on canvas hanging in his studio, Steve uses the method to portray an Italian country road in vivid but calming blues and greens. He fondly refers to the work in progress as his “Obama painting because it has trillions of dots.”

While Steve works with models (his preference) and photographs, he is beginning to paint from memory as well. “After you paint the human form enough, you can pull it from your head; it’s just much harder.” He views this approach as a challenge, one that will give his art the freshness he is aiming to achieve.

[/double_column_right]Similarly, he loves the spontaneity (although Steve is quick to say “planned spontaneity”) that can be attained by completing a painting in a day. Meanwhile, the ultimate for Steve is to arrive at a kind of “virtuosity” in which every element almost effortlessly comes together as he stands before a canvas. “All of a sudden, an angel is on your shoulder,” Steve explained. “Then you have to appreciate where you’re going, be grateful, and say ‘thank you.’”

Photo by Lisa Ferrick

“All of a sudden, an angel is on your shoulder. Then you have to appreciate where you’re going, be grateful, and say ‘thank you.’”

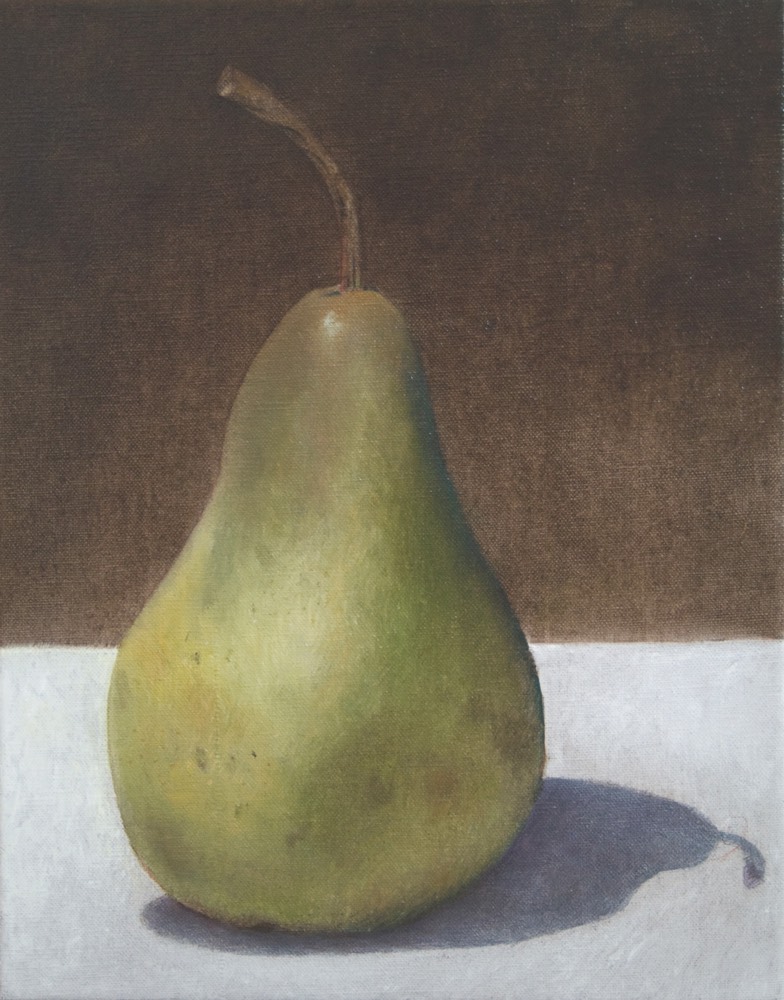

Like many who love the creative process, Steve can get buried in his work and lose track of time. “A day will be a second. But they say, the time you spend creating will be added to the end of your life.” Steve said that simply painting on canvas is fulfilling. “The true joy for me is just being in front of the canvas and applying the paint,” he said. “If I’m doing lemons or a landscape or a pig, it’s all fun.”

Fortunately, Steve does not get tired of painting Napa pigs, his most commissioned work. Besides, each one he creates is unique. “If you say, ‘I want one just like that,’ I’ll tell you that yours will be different in subtle ways.” Steve also reveals that he enjoys his commissioned projects because the vision and process are always straightforward. “They are planned to the nth degree,” he explained.

In Steve’s eyes, planning is essential to producing fine art. Just as the exquisite color and shape of an orchid are not random, Steve’s serenely beautiful oils and sculptures come to life through planned geometric composition. He meticulously determines that composition before starting; straying off course usually leads to disappointment. “If I have a plan and then get into a mode in which the painting thinks it wants to go a different way, I stop and let it sit for a couple of days.”

Unlike many of his contemporaries, who gave up graphic design because they could not get accustomed to the new technological applications, Steve welcomed computerized graphic design. “The Macintosh provided instant gratification,” said Steve. “Before the Macintosh came along, the laborious process of preparing camera-ready art turned me against graphic design work,” said Steve. Frustrated, he gravitated to sales and marketing. Better technology not only led him back to graphic design, but computer graphics also became the primary tool for laying out ideas before translating them either to canvas or to stone. For sculpture, Steve finds that a graphic rendition is essential, and he compares the computer drawing to his stonework at various checkpoints to make certain he is on the right track. In many ways, Steve has orchestrated a perfect harmony between technology and fine art.

Photo by Jessie Shepard

All the same, during his design career, Steve’s identity as an artist remained prominent: long before leaving graphic design to be an artist full-time, Steve painted and sculpted. “I taught myself to sculpt in my driveway twenty years ago,” he said. “I always had an art studio in a converted spare bedroom at home.”

Abundantly thankful to his wife, Karen, for her career that affords him the opportunity to focus on his art, Steve knows that a successful artist has to do more than paint. Marketing the work is essential, but that aspect of the business is a challenge for most. Ideally, he said, an artist will connect with a gallery that believes in the individual’s work and that, therefore, provides the necessary marketing support. “I am fortunate to have Page O’Connor in Sandestin, who has sold several of my works.”

Nevertheless, Steve said, “I am not a vacation artist. People will not pick up my paintings because they had a good time at Seaside.” He concedes that an ongoing predicament for artists is achieving balance between what one loves to paint and what will sell. He feels that once his technique evolves and becomes “good enough,” an urban environment—Atlanta, New Orleans, New York, San Francisco—would best suit his style. “I’m getting there, but I’m not there yet.”

One of his ongoing objectives is to master realism through the abstract. By this he means keeping the brushstrokes fresh so that the paint goes on the canvas just as it should. He names Andrew Wyeth as an example of one who could apply paint without overworking it.

In striving to improve upon his technique and even to cultivate a more definitive style, Steve claims that he has made more progress over the past two years than he had accomplished in all the time up to that point. He attributes part of his growth to the knowledge he has acquired through an online artists’ forum (www.studioproducts.com) sponsored by Cennini—a company that produces the handmade paints, mediums, and other supplies that he loyally uses. “It’s the best forum I’ve found of its kind worldwide that attracts like-minded artists,” explained Steve. “After all of these years, I feel like I am finally learning to paint.”

[double_column_left]The mention of Cennini prompts a discussion of today’s most popular products versus the lead paints and triple-distilled turpentine made the old-fashioned way. “Now they have art schools that don’t even use turpentine,” said Steve. “That’s the most insane thing I have ever heard!” He is also adamant about using lead paint. “I don’t eat it!” Taking time to wash his hands is not an inconvenience to Steve, who finds that lead white, in particular, offers a facility that cannot be reached with titanium or zinc-based whites. From studying the Old Masters and their techniques, Steve contends that to achieve what they did, it simply makes sense to use the same materials. He goes on to explain that the widely marketed pigments are not created for fine art—they are developed for industry purposes—and that artists who use those paints are missing out. Again, he prefers the hues of Cennini, which are packed with pigment and much more intense and, above all, are made specifically for realist oil painting.

[/double_column_left] [double_column_right]

Photo by Steve Wagner

“I taught myself to sculpt in my driveway twenty years ago. I always had an art studio in a converted spare bedroom at home.”

Photo by Jessie Shepard

Colors and textures come equally into play in choosing media for sculpture. With the exception of one torso, Steve’s pieces so far are all women’s heads, strongly inspired by Modigliani’s paintings. His favorite medium is marble, which not only presents a clear, consistent color throughout, but also sings or rings when it is tapped. He enjoys working with limestone as well, though it can have blemishes that must be addressed. The boutique jewelry store Bijoux de la Mer in St. Barts shows several of Steve’s pieces, which are made of coral. To work with coral, Steve is cautious and always wears a mask. “Unlike marble, which is calcium-based, coral is highly toxic,” he said, “as dangerous as asbestos.” His least favorite stone is soapstone because the sound it makes is a thud rather than a pleasant ring.

What rings true about Steve Wagner is his admiration for the beauty he finds in nature and his passion to interpret what he sees onto canvas or into stone. By studying nature, Steve has learned that neither nature nor art needs to be perfect to be admired, yet he clearly sets the highest standards. “There are a lot of artists who are good, but very few who are great,” he said. “In my lifetime, if I could have just one great painting, then that would be wonderful.”

— V —

To see more of Steve Wagner’s art, go to: http://www.stevewagnerart.com

Steve Wagner, Portrait of an Artist from VIE Magazine on Vimeo.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE