vie-magazine-opioid-crisis-in-teens-hero-min

Equal Opportunity Killer

By Tori Phelps

With the opioid epidemic crossing every socioeconomic line ever drawn, an expert breaks down what families need to know.

There was a time when teaching kids about drugs was fairly straightforward. Nancy Reagan gave very succinct advice: “Just say no.” But today, when you’re as likely to get hooked on a legally dispensed substance as you are on something exchanged in a back-alley deal, the war on drugs has taken a complex turn. The only simple aspect is the number of bodies piling up because of it.

And if you think opioids aren’t in your neighborhood, then you probably don’t know your neighbors very well.

Dr. Laura Happe, a pharmacist and expert in opioid addiction, understands the pervasiveness of the epidemic because it’s literally her life’s work. During her tenure as Humana’s chief pharmacy officer, she led the national health plan’s opiate task force. Currently, she edits the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy and teaches at the University of Florida and Wingate University. Her lesson plans are a far cry from what she learned in lecture halls, however. “I was part of a generation of pharmacists and physicians that were told opioids weren’t addictive if you were truly in pain,” she recalls.

That false information wasn’t limited to one classroom or one university. It was the message of the day, spread far and wide in what she calls a perfect storm of genuine misunderstanding and incredible greed. The result was millions of medical professionals who didn’t think twice about prescribing and filling prescriptions for drugs like hydrocodone and oxycodone.

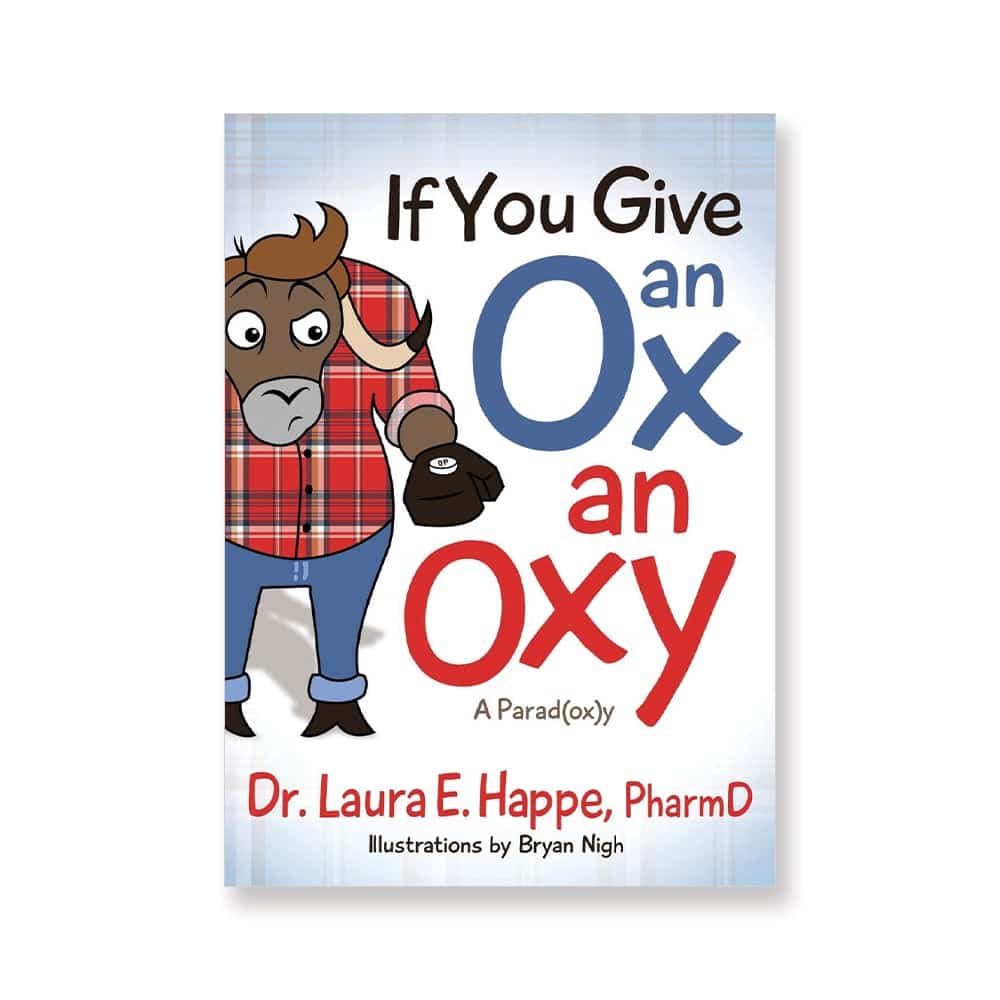

Happe sees her multifaceted professional life—which includes authoring If You Give an Ox an Oxy—as a chance to right some wrongs through education. Her focus on preventing substance use disorders (the preferred term for “addiction”) includes helping people understand that, while opiates do have appropriate uses, they’re mostly limited to short-term pain following major surgery, pain associated with diseases like cancer, and end-of-life care.

They’re not good for much else.

Probably the most significant misuse of opioids, she says, is for chronic back pain. Interestingly, research shows that opiates aren’t effective for that kind of pain. But patients continue to receive prescriptions and then escalate the doses to seek more effective relief, only to end up as overmedicated shells of their former selves. To add insult to injury, it takes a long time to taper off opiates, and there aren’t good alternatives once you start.

A quick fix is the American way, though, and the health-insurance system feeds into that cultural bias by covering medications rather than, say, massage and acupuncture.

New pain diagnoses provide an opportunity to make the biggest difference in opioid misuse, Happe says, especially when the attending physician is educated in pain relief that does work. Physical therapy, yoga, and other modalities can get people moving rather than popping a pill. A quick fix is the American way, though, and the health-insurance system feeds into that cultural bias by covering medications rather than, say, massage and acupuncture. “There’s no incentive for people to try those other things,” Happe says of the catch-22. “We have to start at a systems level by covering them and then get people to try them.”

Yet addiction prevention starts as much in the home as it does in the doctor’s office. Parents might think they can control their kids’ exposure by refusing unnecessary prescriptions for minor children, but Happe insists such notions are utterly, dangerously wrong. A kid’s introduction to opioids often goes something like this: a friend swipes a few pills from a parent’s medicine cabinet and shares that cache with pals. What’s the harm, they wonder? It’s prescribed by a doctor, after all.

One uninformed decision can trigger addiction and, potentially, overdose. And parents generally don’t recognize early signs of opioid misuse in their kids because they can mimic typical teen ennui. Opioids essentially hijack the brain’s pleasure pathway—delivering sudden, overwhelming bliss—so everyday moments of contentment, from cuddling the family’s new puppy to scoring the winning goal, don’t cut it anymore. “When someone is using opioids, they become accustomed to that rush,” Happe explains. “The things that used to bring them joy no longer do.”

Only 16 percent of parents talk to their kids about opioids and prescription drugs, possibly because they don’t understand the danger; it’s also possible that they don’t believe it happens in educated or influential families. But no one is immune. People who wouldn’t normally dream of using street drugs are chasing illegal sources when they’re cut off by the medical system. And drugs like heroin, which used to be associated with inner cities, are now a white-collar problem.

The staggering rate of opioid deaths is mostly a result of “street chemists” who knowingly and unknowingly sell deadly pills. Tainted drugs are one problem, but lethal doses are the bigger one. In pharmacological terms, morphine is the benchmark by which the potency of other opioids is compared, Happe explains. Morphine is powerful enough, but fentanyl, a common street drug, is one hundred times stronger. Carfentanil, another widely available street drug, was created for use in large animals—not people—because it’s too risky for human consumption. “The margin of error is very small for Carfentanil,” she says. “It’s ten thousand times more potent than morphine; it’s literally the size of one grain of sand when compared to a tablespoon of morphine. When street chemists mess up, people die.”

The medical community is making strides with policies limiting the number of opioids in a single prescription and a system of checks and balances between pharmacies and insurance companies. New technology can even help predict which patients might be more prone to substance misuse before a prescription is even written. But what makes the opioid epidemic such a unique problem is that it’s not contained within the medical community. There’s no exact parallel, Happe says, though public health crises like drinking and driving might be the closest. Much progress has been made in impaired driving over the last few decades because institutions, from schools to the criminal justice system, targeted specific populations with individual messages, producing widespread change without necessarily collaborating.

A similar approach is required to stem the tide of opioid addictions and deaths, Happe believes. “It’s easy for companies, individuals, or even legislators to say, ‘How can I really make a difference just attacking this one little aspect?’ But if we all change the things we can, together we can put an end to this,” she says.

— V —

For more information, visit LauraHappe.com or connect with Dr. Happe on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Tori Phelps has been a writer and editor for nearly twenty years. A publishing industry veteran and longtime VIE collaborator, Phelps lives with three kids, two cats, and one husband in Charleston, South Carolina.

If You Give an Ox an Oxy

If the title sounds familiar, that’s by design. When tackling a subject as tough as opiate and prescription drug abuse as Dr. Laura Happe does in If You Give an Ox an Oxy, referencing something like the beloved children’s book series by Laura Numeroff can be sweet comfort to kids and parents.

The slim volume delivers a thorough explanation of opioid issues in kid-appropriate language, with engaging illustrations that help hold the attention of little eyes. A glossary of terms, plus questions that get children thinking and talking, create an ideal jumping-off point for parents, a boon for those who aren’t sure how to navigate the reality that opiates are both dangerous and medically appropriate.

As for the “right” age to begin talking, Happe doesn’t think there’s a one-size-fits-all answer. Her thirteen-year-old and eight-year-old have already been introduced to the topic, and she recommends letting your child’s emotional maturity and what’s going on in your community help you decide. But finding the perfect time is less important than just diving in, she urges, adding that uninformed kids are incredibly vulnerable. “If you don’t have the conversation, someone else is going to,” she promises.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE