vie-magazine-icons-modern-art-hero

Claude Monet, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1866. Courtesy Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Masters of the Modern Age

Iconic Art Collection Reunites in Paris

By Tori Phelps | Photography courtesy of Fondation Louis Vuitton

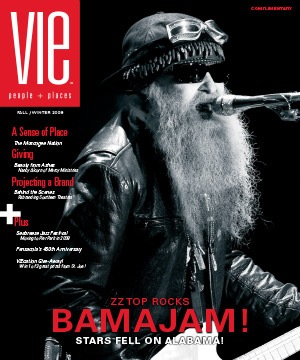

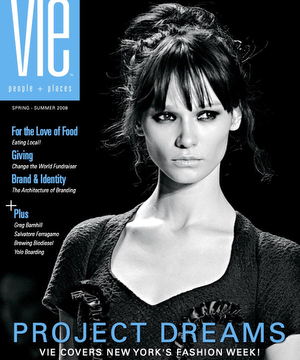

Louis Vuitton is synonymous with exclusive handbags and luxe pieces of luggage. But through its Paris-based Fondation Louis Vuitton, both a museum and an emerging cultural touchstone, the legendary design house is now an art world VIP, too.

The institution has forged a substantive reputation within a few short years, but its latest exhibit leaves no doubt that it is, indeed, a force to be reckoned with. In Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection, the young Fondation Louis Vuitton showcases a collection of works that helped launch an artistic revolution. And it hasn’t been seen by the public at a single location for seventy years.

Visitors will come face-to-face with paintings by Picasso, Monet, and Van Gogh—just a few of the heavy hitters on display from October 22, 2016, through February 20, 2017. But the exhibition is as much about the man behind the collection as the artwork itself.

Vladimir Tatlin, Nu, 1913. Courtesy Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Among the richest and best-known industrialists in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Moscow, Sergei Shchukin was born to money, married money, and made even more money in the textile trade. After the first of four children had arrived, Shchukin and his wife cemented their fairy-tale image by moving into the Trubetzkoy Palace. It was then, at the height of social and economic success, that Shchukin turned his attention to art collecting.

It was a clichéd hobby of the wealthy, but his interest wasn’t feigned. Art was a family obsession, from an uncle who regularly hosted famous painters in his salon to a younger brother who had moved to Paris to dedicate his life to art. Shchukin’s love affair with French Impressionists began with the purchase of two Pissarro street scenes, followed by his first Monets: Rocks at Belle-Île and Lilacs at Argenteuil. In the ensuing decade (1897–1907), his collection expanded to include thirteen Monets, eight Cézannes, and sixteen Tahitian Gauguins. Works from Van Gogh, Renoir, Degas, and many other artists followed, filling the walls of his palatial home.

[the_blockquote]Shchukin returned home and continued his avant-garde art pursuits, becoming enthralled with newcomers like Matisse, with whom he built a genuine friendship. He was also a Picasso devotee, and by 1914, Shchukin owned fifty Picassos.[/the_blockquote]It wasn’t long before people took notice of the impressive collection. Everyone from intellectuals to art critics and young painters wanted to get inside the Trubetzkoy Palace, and Shchukin’s collection influenced other affluent Muscovites to begin purchasing French Impressionist works. By 1905, Shchukin was perhaps better known for his collection of radical artworks than for his business prowess.

Then came the tragedies. Within a few years, two sons committed suicide, he lost his wife suddenly, and his younger brother died in Paris while Shchukin was visiting the city. Feeling somehow responsible for these gut-wrenching events and seeking to bring some meaning to his life, he wandered across the Sinai Desert, ending up at the sixth-century Monastery of Saint Catherine.

[double_column_left]Georges Braque, Le Château de la Roche-Guyon, 1909. © ADAGP, Paris 2016. Courtesy Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Whatever he was looking for, he apparently found. Shchukin returned home and continued his avant-garde art pursuits, becoming enthralled with newcomers like Matisse, with whom he built a genuine friendship. He was also a Picasso devotee, and by 1914, Shchukin owned fifty Picassos. While the thought is gasp-inducing to modern audiences, his contemporaries were gasping for a different reason. So unimpressed were they by these artists that his wealthy cronies assumed tragedy had driven Shchukin mad. There was such an ugly outcry at the unveiling of Matisse’s The Dance and Music, in fact, that Shchukin was almost swayed into not buying them.

[/double_column_right]In the end, he didn’t really care what his peers thought. Shchukin understood the significance of his collection and decided to open his palace to the public a few days a week. He was acclaimed for his courage by art lovers and progressive artists, and his home-turned-gallery was a very real reason that Russian Cubism, Proto-Cubism, Constructivism, and Suprematism gained a sizeable following.

The First World War and the February Revolution’s overthrow of the Russian monarchy changed Shchukin’s life forever. Seeing the anticapitalist writing on the wall, he fled Moscow in 1918 with forged passports and diamonds hidden inside a doll. He lost his home, his country, and the breathtaking art collection he’d poured his heart and soul into for most of his adult life. The quiet life he found in Paris with his remaining son, new wife, and young daughter was a consolation, though—and far less complicated than what his collection was about to face.

Henri Matisse, La Desserte, Harmonie en rouge, printemps-été 1908 © Succession H. Matisse. Courtesy Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Three months after Shchukin’s departure, Lenin decreed that the Trubetzkoy Palace and its 256 pieces of art now belonged to the people. Shchukin’s collection eventually joined that of his friend, Ivan Morozov, and those of other collectors to create the eight-hundred-piece State Museum of New Western Art (GMNZI), the world’s most illustrious modern art museum.

In the early 1930s, some Shchukin collection pieces were transferred to the Hermitage in Leningrad. Ten years later, on the brink of the German invasion, Moscow museums shut their doors and shipped their treasures beyond the Ural Mountains. At the end of the war, Russia again underwent a seismic ideological shift, and realistic art was deemed more appropriate for the new Socialist regime. Stalin decreed that the GMNZI and its contents should be nationalized—a nicer term than “stolen”—and the artwork divided among provincial museums. Anything held back would be destroyed.

[double_column_left]Edgar Degas, La Danseuse dans l’atelier du photographe, 1875. Courtesy Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Paul Cézanne, L’Homme à la pipe, 1890-1892. Courtesy Pushkin Museum, Moscow

This mandate wasn’t something the directors of the Hermitage Museum and Moscow’s Pushkin Museum could stomach, however. They pleaded and bargained with the academic community, finally convincing decision-makers to split the art between the two museums. So passionate (and panicked) were the directors that the division was completed in a single day. For decades, the pieces were kept under wraps, waiting for some future time when artwork was no longer considered a national threat.

That time arrived as a whisper rather than a shout. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, pieces from the Shchukin collection quietly began reappearing, first at the Hermitage and then on other museum walls. Today, the masterpieces Shchukin so fearlessly threw his money and reputation behind are once again available for public viewing.

Not that most people have had an opportunity to see them. In fact, Icons of Modern Art marks the first time this collection will be presented outside Russia. For the landmark occasion, the curators culled pieces that narrate the beginnings of modern art and how it impacted—and was impacted by—world events. Fondation Louis Vuitton has done its part by devoting the entire 25,800-square-foot, four-level Frank Gehry–designed building to the exhibition. Also, thanks to curatorial magic, visitors will experience a unique layout that evokes both the architecture of the Trubetzkoy Palace and the method in which Shchukin displayed his collection.

[double_column_left]While the project also includes an impressive program of dance and music events, as well as an international symposium, the art is clearly the main draw. Of the 160 pieces, 130 are from the Shchukin collection and represent the main thrust of what he accomplished from 1898 to 1914. Impressionists and Postimpressionists are represented by artists like Monet, Renoir, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Pissarro, Cézanne, Degas, and Gauguin. Among other household names are Matisse (representing the Fauves) and Picasso (representing the Cubists), whose work alone occupies a whopping twenty-nine spots in the exhibition.

Like the man who accumulated most of the collection, Icons of Modern Art has an unapologetically ambitious agenda. The exhibition is a gleeful celebration of art’s triumph over oppression. It also highlights the extraordinary artistic exchanges between France and Russia in the early twentieth century, but perhaps most importantly, it’s a reminder that one person’s unwavering support of new creative expressions can change the art world—and the rest of the world—for the better.

[/double_column_left] [double_column_right]Christian Cornelius (Xan) Krohn, Portrait of Sergei Shchukin, 1916 © ADAGP, Paris 2016. Courtesy Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE