vie-magazine-galapagos-islands

Letters from Latitude Zero

The Galápagos Islands

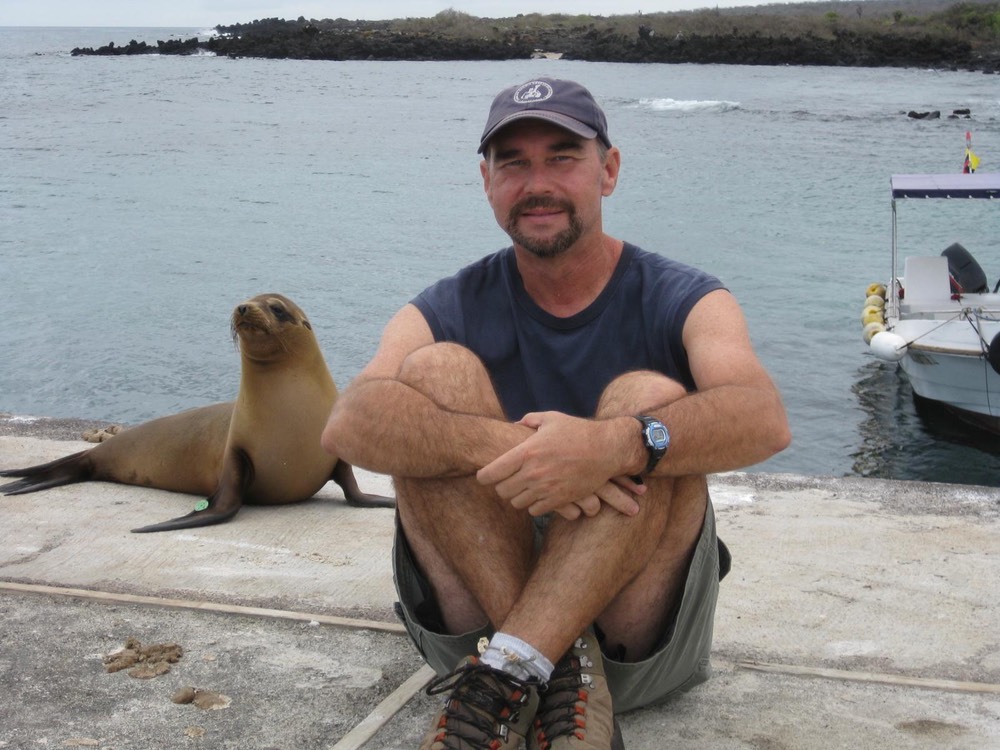

By Dale Foster

Two thousand nine was a celebratory year for the Galápagos Islands. It was the 200th birthday of its most famous visitor, Charles Darwin. It was the 150th anniversary of the publication of his seminal work, On the Origin of Species, and it was the 50th anniversary of the Parque Nacional Galápagos, caretaker of the islands. The author spent four months living in Galápagos where he worked as a volunteer at a scientific research station.

March 25, 2009

“… it seems as though at some time God had showered stones; and the earth that there is, is like slag, worthless . . .”

Such was the first impression of Fray Tomás de Berlanga in 1535 when, blown off course sailing from Panama to Peru, he became the first confirmed human on the Galápagos Islands. Flying into Baltra Island, I cannot help but have similar feelings. My research had shown emerald waters with beautiful beachscapes inhabited by unusual creatures. Instead, what confronts me is a desolate prehistoric landscape of lava rocks and a few scant cactus trees.

I am staying on Santa Cruz Island, and at first sight, it is similarly unimpressive. The Galápagos archipelago has been described as one of the most unique, pristine, undisturbed, and biologically outstanding areas on earth. Viewing Puerto Ayora, the largest city and commercial center of the Galápagos, I am beginning to doubt the validity of that statement. Driving by rustic dwellings made of concrete block and dusty lava rock side roads, I am struck by how impoverished the area looks. Civilization, as I know it, is a hemisphere away.

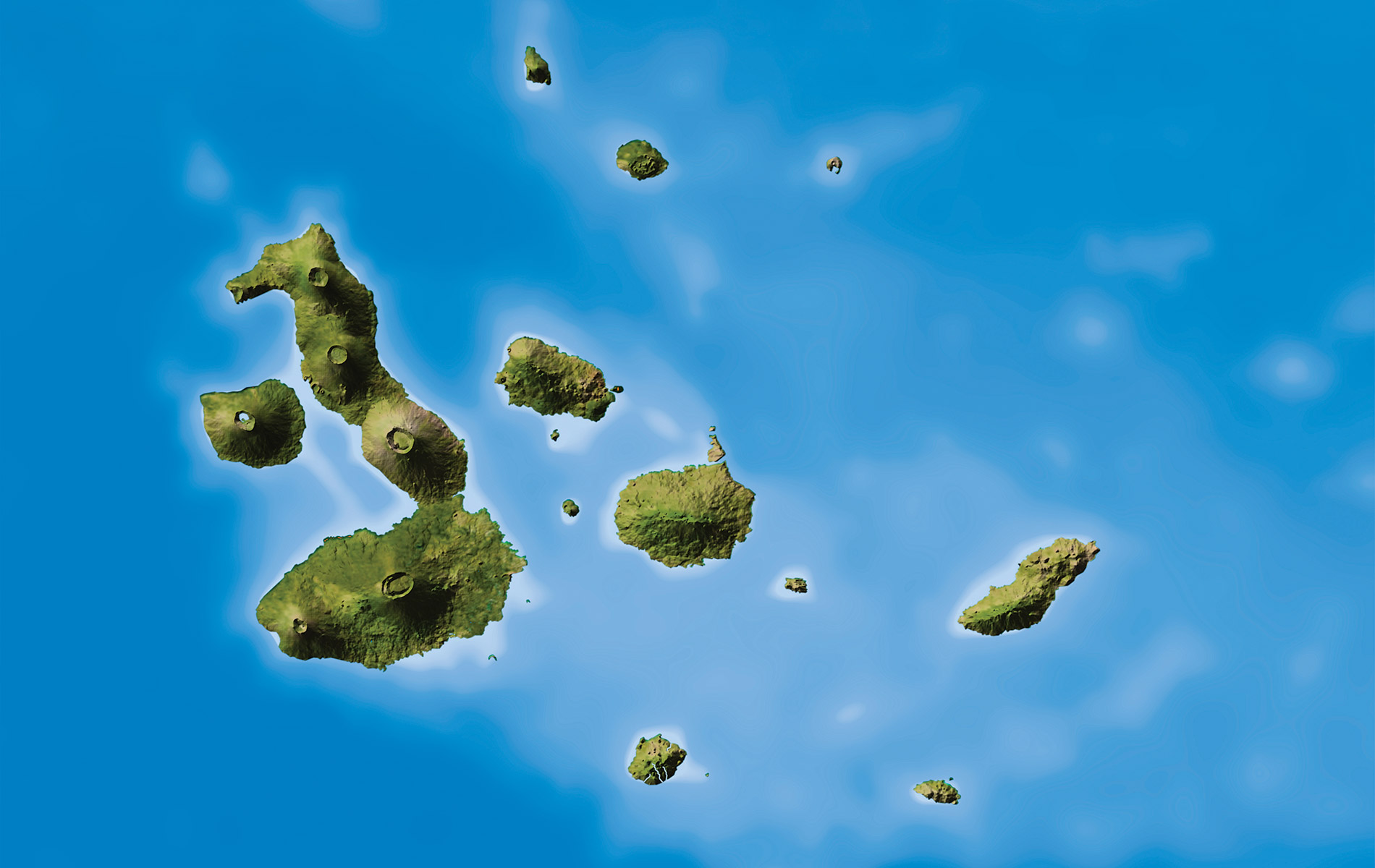

The Galápagos Islands lie six hundred miles off the coast of Ecuador. There are thirteen major islands, six smaller islands, and hundreds of tiny islets. Of these, only four are inhabited by humans. It becomes apparent to me that the islands’ inhabitants—human and non-human—are carving out a meager existence in a harsh and unforgiving land. Why have they chosen to occupy these rugged and imposing volcanic peaks?

April 1, 2009

“Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance.”

—Charles Darwin

The town of Puerto Ayora is a beehive of activity with taxis, souvenir shops, restaurants, dive centers, cruise ships, and hotels. Lonesome George, a giant tortoise of more than seventy years, lives just a couple hundred yards from me. He is supposedly the rarest species on earth and thought to be the only extant giant tortoise from the isolated island of Pinta.

Black marine iguanas are plentiful, making themselves at home anywhere along the shoreline, including restaurants and sidewalks. They seem to be very docile, moving only to swim in search of food.

While exploring Tortuga Bay, I find familiar turtle tracks in the sand leading from the water to the dune line. Such scenes along the Gulf Coast would be marked by flags and signs. No worries here about artificial lighting from condos or beach houses—95 percent of all the land and sea area is a national park. The sea turtles have been nesting here for millions of years and will continue to do as nature calls, as long as humans do not interfere.

I am struck by the way the animals behave here. Marine iguanas and finches seem uninhibited by the presence of a human and often venture very close. They seem to have no inherent fear of us larger creatures. The same is true of the playful sea lions that roam the harbor. Since the Galápagos Islands remained virtually uninhabited until the nineteenth century, it makes me wonder if fear isn’t a learned trait, and since these animals have spent relatively little time with humans, they have no need to fear us.

May 14, 2009

Fear and Loathing in Galápagos

I am on Isabela Island, near where the equator passes through the island’s northern point. It is the largest of the Galápagos Islands and one of the most active volcanic hotspots on the planet. I ride by horse to the rim of Sierra Negra, the world’s second-largest volcano. It is one of five volcanoes on the island and last erupted in 2005. From there, I hike to the top of Volcan Chico, where you can still feel the heat coming up from holes in the lava. I have a panoramic view of Fernandina, the latest active volcanic island in the archipelago, but its La Cumbre volcano is not erupting that day.

Standing on the moon-like terrain of the volcano craters and seeing the hardened lava flows, one can really sense that this was how the planet was formed. What incredible power, heat, and energy must be necessary to explode molten rock and lava rivers from the middle of the earth. But, magically, life does eventually begin to form on this barren field, as evidenced by sporadic cactus shoots. Over the next millions of years, other plants and animals will occupy this now desolate landscape.

Isabela was a penal colony from 1944 to 1959, when the prisoners rebelled. The colony was famous for the Muro de las Lágrimas (Wall of Tears), a 22- by 300-foot lava rock wall constructed by the prisoners under cruel conditions. Adding convicts to the assorted list of pirates, whalers, robber barons, tyrants, outlaws, adventurers, smugglers, expatriates, misfits, and castaways who have occupied these islands only enhances the uniqueness and mysteriousness of this place.

Today, Isabela is often considered the most beautiful site in the Galápagos. It has a population of fewer than two thousand people, most living in the small peaceful town of Puerto Villamil. To me, it is the quintessential tropical village with sandy streets lined by coconut trees, a tranquil turquoise harbor, large beaches, crystal clear water, sea lions, marine iguanas, giant tortoises, white-tipped sharks, blue-footed boobies, pink flamingos, and penguins. Time does indeed seem to slow down on Isabela, which is ironic, considering that locations near the equator are moving faster than any other point on the earth. The laid-back atmosphere of Puerto Villamil contrasts sharply with the bustling tourist town of Puerto Ayora. Returning to Santa Cruz will be like going to New York City.

May 27, 2009

“Galápagos, Where Life is Just a State of Mind.”

—Kurt Vonnegut

I continue my island-hopping to San Cristóbal. Named in honor of Saint Christopher, this was the first island in the Galápagos on which Charles Darwin landed in September 1835. It is from here that Darwin began to form his now-famous theory of evolution.

The island is home of the provincial capital of the Galápagos and is undergoing several noticeable improvements such as a beautiful malecón (levee), newly paved streets, an airport, and a first-class interpretative center. Puerto Baquerizo Moreno is the main city and overlooks perhaps the most scenic port in the eastern Pacific. One of the most interesting things about the city is that the sea lions consider themselves as much citizens of the town as humans. They occupy large stretches of beaches and swim along the edge of the malecón. They make themselves at home anywhere in town they like.

I travel to Puerto Chino on the island’s southwest tip. It is a small stretch of sandy beach but with ample area for hiking and exploring. The wildlife includes blue-footed boobies, sea lions, and frigate birds. I hike along the rocky coastline into some difficult terrain, wondering if I were the first human to ever set foot on a particular rock or ledge.

The look and feel of San Cristóbal is a tempting middle ground between the remote tranquility of Isabela and the hectic Santa Cruz. The harbor is lined with sailing vessels of all kinds, including the sailboats of some captains I meet who are sailing around the world. For them, and for me, San Cristóbal is a welcome and scenic mooring.

An interesting transformation of attitude is taking place within me. Among these bleak surroundings, I am beginning to see beauty—color on a backdrop of barren landscape is a sight to behold. There is nothing artificial here. What you see is what nature has taken millions of years to produce, and understanding that fact leaves me in amazement. What I once thought of as impoverished living conditions are actually totally sufficient to meet the needs of island life. Why would you want more? Maybe Galápagos is, indeed, a tropical paradise.

June 19, 2009

“But the special curse, as one may call it, of the Encantadas, that which exalts them in desolation above Idumea and the Pole, is that to them change never comes; neither the change of seasons nor of sorrows.”

—Herman Melville

When not working, I am hiking and sightseeing on Santa Cruz: climbing to the top of Cerro Crocker and Cerro Puntudo, the highest points on the island; swimming in the turquoise waters of El Garrapatero beach and the crystal clear water of Las Grietas, a rare inland lake; and seeing many giant tortoises at Rancho Primicias and El Chato.

The Galápagos Islands are a paradoxical paradise. They are a place where some have been forced to go, while others have yearned to live there. It is one of the most isolated and inhospitable environments on the planet, yet life exists here. It must be a “biological imperative”—life just exists, and it grows where it can. It adapts to conditions it cannot easily overtake. Where it cannot adapt, life simply dies. But the human population of the islands is growing. Ecuadorians from the mainland come in search of jobs and a better life. The Galapaganos, those born and raised on the islands, are caught in the middle of an economic revolution but with little experience or training to deal with the massive changes.

Many come to Galápagos to lead the simple life, yet the simple life is getting harder to find as increasing tourism, expanding island population, and building construction continue to grow. They are facing the “economic imperative” of satisfying unlimited wants with limited resources. Ecology is what drives the tourism engine of Galápagos; yet, as more tourists and settlers come to the islands, the more the ecology is impacted. History has proven Melville wrong; the Galápagos are changing—geologically, environmentally, and socially. It remains to be seen if the “special curse” of the Enchanted Isles will result in sorrow for the human and non-human inhabitants.

The human story of Galápagos is one of potential and subsequent failure. Throughout its history, Galápagos has proven again and again how unsympathetic a place it can be. Galápagos is a severe environment . . . in some ways, not fit for man nor beast. However, the animals and plants that inhabit the islands have adapted to the environment, whereas man must adapt the environment for his needs. The islands know no dreams, only the brutal reality of wind, sun, and sea. Nature, with laws of biology and geology, is the ruler here . . . not man, and those who have not paid notice have often paid with their lives.

July 4, 2009

“Now I was thankful to realize that I was here at all, and that I had the great honour of being one with all about me…”

—William Beebe, Galápagos: World’s End

Independence Day in the United States but no mention here. It is a wonderful evening highlighted by fireworks in town—coincidently, in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Parque Nacional Galápagos.

Today is a good day for reflection, and after three months on the islands, I am beginning to notice changes. The isolation here is more than just physical. It is intellectual and informational if you choose, and it is easy to care less about what is happening in the rest of the world. “Living in the moment” is truly part of life here, and focusing on the necessities of life simplifies it greatly. This wildlife sanctuary can also be a refuge for the human spirit.

Some people have more worries than dreams, and for “Galápagringos” like me, living in the Galápagos is a good cure for the ailments from too-much-in-this-world American society. The sound of the Pacific surf or the sighting of a blue-footed booby invigorates the soul. Certainly, living in an island community in a lesser-developed country has its challenges. But as a personal journey, it is refreshing and cleansing to see how other countries and cultures live on a day-to-day basis. It provides a different insight into the world in which we live and reduces once seemingly big problems down to their proper dimension. Living in a “third-world country” can provide many lessons for those in the “first world”—lessons such as conservation, friendship, getting by with less, and slowing down the pace of our lives to a more tranquil level. Standing in the third world, it is easier to see the conspicuous affluence, wastefulness, and exploitation of the developed world. Achieving the American Dream has not come without costs, and these costs are felt far beyond the shores of the United States.

July 12, 2009

Galloping Around Galápagos

Visited Floreana, the island which hosted the first human settlement in the archipelago. Puerto Velasco Ibarra, a small town of a hundred people, is only a few buildings. Because the island has a relatively stable supply of fresh water, it has been inhabited the longest of any of the Galápagos islands. In the 1930s, Floreana was colonized as a utopian community and reminds me of similar efforts in Fairhope, Alabama. The island later became famous for intrigues involving love, hate, and even mysterious deaths, as chronicled in the book, The Galapagos Affair.

The diving and snorkeling around the islands offer amazing adventures. The Galápagos are one of the few places in the world where people actually come to swim with the sharks, not run away from them. The waters are wonderfully clear, offering astonishing views of colorful king angelfish and sea lions as they come down to play. The sea lions are truly graceful underwater and seem to have no fear of humans.

The Galápagos are no Club Med; the terrain is treacherous, and the temperature is incredibly hot much of the year. The uniqueness of the Galápagos experience is to see creatures and plants in the context of their natural habitat, but it is not a zoo or an artificially created exhibit. Here, you see plants and animals as they lived thousands of years ago. You experience the harsh climate, the rugged terrain, the waves and the wind, and all the other elements experienced by the flora and fauna. As such, Galápagos is an “involved experience,” not a static display in a museum. What Galápagos offers is a first-hand experience with nature, with lessons on preserving the habitat and learning about the lives of these creatures and plants.

It is ecological conservation that makes Galápagos “holy ground.” The staff of the Parque Nacional Galápagos (PNG) are charged with showcasing the natural beauty of the islands while minimizing the impact of humans—and the risk is not just from tourism. Introduced species of plants and animals also endanger this unique and fragile ecosystem. The lack of predatory animals and invasive plants are part of the reason life is able to survive here. But humans have brought with them species of goats, pigs, wild dogs, cats, and mora (blackberry) that compete with the islands’ native flora and fauna for precious few resources.

July 29, 2009

“You call someplace paradise, kiss it goodbye.”

—Don Henley

My last day in Galápagos. Once so remote and shrouded in mystery, Galápagos is now in danger of being overrun by its popularity. Puerto Ayora is a frontier town with a “gold rush” feel to it. Galápagos is a unique island setting, with a collection of animals and plants unparalleled anywhere on earth. But we are at risk of plundering this paradise, and some say we have already gone too far.

Just during my time here, I have noticed a substantial increase in the number of tourists. In some places, especially Isabela, it is clear that a comfortable upper limit has been reached, and further increases in the number of visitors will overwhelm the already fragile infrastructure of the small towns and villages.

It seems Galápagos is destined to become one of the premier tourists destinations in the world as restrictions on tourists’ numbers are set to explode. The new muelle (dock) in Puerto Ayora and the planned new airport on Baltra all point to Galápagos gearing up for a tourism boom. The impact on the environment could potentially be devastating, although it may not be evidenced in full in our lifetime. Puerto Ayora and surrounding communities are already exceeding their natural boundaries and capacities for human habitation. Electricity, water, and communication services are all intermittent here.

Galápagos is a pristine laboratory for studying flora and fauna under isolated conditions. Few, if any, places in the world offer us the opportunities for scientific research found in Galápagos. This natural laboratory, relatively undisturbed in Darwin’s day, was credited by him as “the origin of all my views” on evolution and the origin of species. It is in this laboratory that many of nature’s secrets can be found, which can then be applied to a better understanding and better stewardship of our world. But Galápagos also serves as a microcosm of the inevitable conflict between humans and ecology. In Galápagos, we can control the destiny of the environment to a certain degree, unless the greed and destructive nature of humans interfere. If we are not able to save Galápagos, what chance is there for our saving the rest of the planet?

Suggested Reading:

Galápagos: A Natural History (Paperback)

by Michael H. Jackson

Publisher: University of Calgary Press; 2nd edition (1994)

Galápagos: The Islands That Changed the World (Paperback)

by Paul D. Stewart

Publisher: Yale University Press (2007)

Galápagos: Preserving Darwin’s Legacy

Tui De Roy, Editor and Principal Photographer

Publisher: Firefly Books (2009)

— V —

Dale Foster is a former library director, archivist, television and radio producer, writer, inventor, and consultant. He served four months as a volunteer librarian at a scientific research station in the Galápagos Islands. He currently lives in Santa Rosa Beach. When not sailing, he volunteers for worthy library projects around the world.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE