vie-magazine-kathy-fincher-art-hero-min

The Dream Keepers by Kathy Fincher | Dry pastel and watercolor on museum rag board, 40 × 30 in. | The original painting is in the George W. Bush Presidential Library.

Let Freedom Ring

A Dream Keeper at Work

By Sallie W. Boyles | Artwork by Kathy Fincher

A measure of unbridled freedom and utmost discipline produces fine art. Both are ingrained in artist Kathy Andrews Fincher. While growing up in her hometown of Duluth, Georgia, thirty minutes north of Atlanta, she was usually riding her horse through the local lake or swimming in it with her four brothers. Like every other child, she was sent outdoors with the freedom to be a kid until the sunset signaled time to head home.

Kathy’s mother—valuing education and deeming that her only daughter, a rising high school sophomore, needed some ladylike qualities—sent her to Brenau Academy, an all-girl boarding school in Gainesville, Georgia. Finding little in common with girls who wore makeup, she was grateful for Jenny McCrary, a fellow student with three brothers of her own. Thanks to Jenny, Kathy gained a precious friend and a treasured art teacher.

“Lydia McCrary, Jenny’s mother, had studied art at the Louvre in Paris,” says Kathy, “and the museum’s curator had spent his life rediscovering the mediums of the Old Masters.” By befriending the curator’s wife, Lydia learned the classical methods directly from him. She, in turn, adhered to the techniques in teaching through her studio in (of all places) small-town Gainesville. Kathy claims that Lydia immediately accepted her as a student to lure Jenny there. Although Jenny quit after four classes, Kathy, who received permission from Brenau to leave the campus for her art education, ended up studying under Lydia for twenty years.

“I gained this tremendous background in drawing, which has not been emphasized for a long time,” Kathy says. “The emphasis was void of color, but it was a life lesson on perfect values. The finished work looked like a black-and-white photograph.”

Explaining her disciplined training, she continues, “You drew for four years in charcoal before you used color. When you painted, everything was in pure white. Various rooms in the studio contained the subjects—pure white plasters of busts, reliefs of florals and figures, and statues of Renaissance influence.” All were meant to be studied. “Doing in-depth research on every piece of art you approached was one of the main lessons I took from Lydia,” Kathy says. “On top of that, you strived for every piece of work to be a masterpiece. It was not unusual to begin a painting and know that you’d be working on it for three to four years.”

- The Retirement Gift | Available as giclée canvas, 24 × 18 in.

Kathy later transferred from Brenau College (Brenau University today) to the University of Georgia as a junior to major in art. “My first assignment was to paint three nudes on a three-to-four-foot canvas,” she recalls. “I asked the teacher how to mix flesh tones; Lydia still had me drawing.” The answer then and repeatedly thereafter was to “express yourself.” Kathy states, “There was no organized teaching. Because of that, I changed my major to outdoor parks and recreation and spent my senior year living on a wildlife refuge in the Okefenokee Swamp. I completely turned against the arts.” Instead, she turned to the great outdoors.

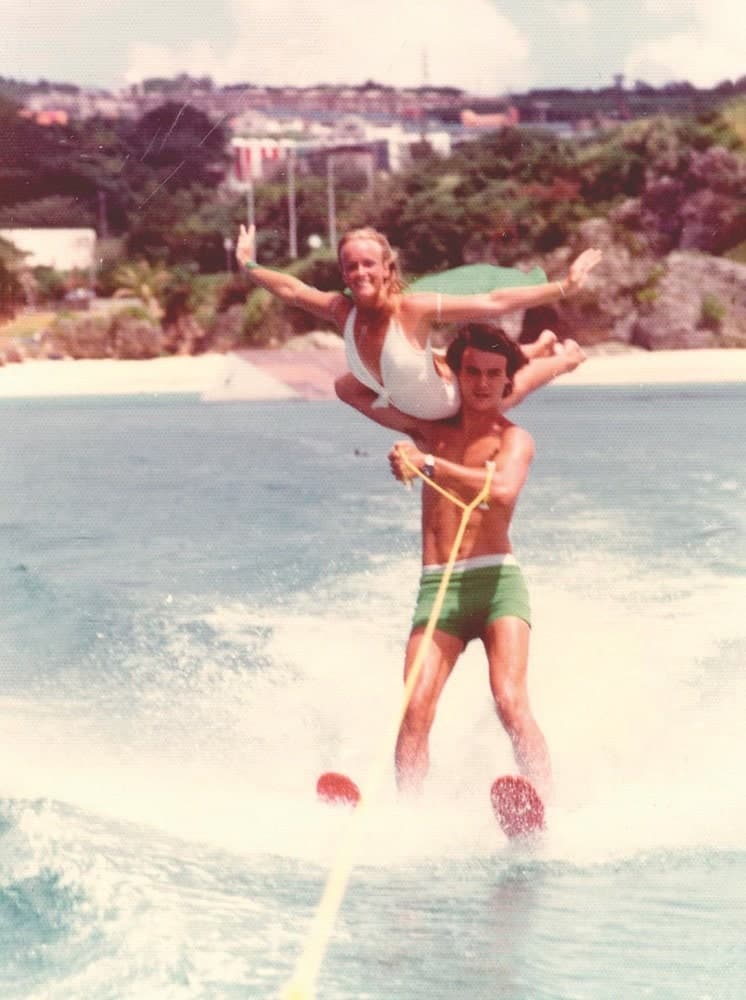

A natural athlete, Kathy and her extended family had spent many Sundays after church on Georgia’s Lake Lanier. “We would all tie our boats together and swim,” she says. Seeing a kite skier inspired her brothers to build a flat kite to ski behind their boat. When Lake Lanier Islands formed a ski team, Kathy (in college) and her brothers (in college and high school) were hired to perform tricks in their shows.

She next qualified for a position on a US team of water-skiers that entertained international audiences at the 1975 World’s Fair, Expo ’75, in Japan. Additional work as a performer and trainer presented a gig that had her skiing off Navy Pier in Chicago and then wowing crowds for the legendary Tommy Bartlett Show.

“I became so obsessed with snow skiing that I practiced every night in my mind. In my sophomore year in college, I worked it out with Brenau that I would cut classes on Fridays and Mondays to teach snow skiing over the weekend in North Carolina.”

“For about five years, I was waterskiing in the summer and snow skiing in winter,” says Kathy. Jenny’s family had introduced her to the winter sport. “I became so obsessed with snow skiing that I practiced every night in my mind. In my sophomore year in college, I worked it out with Brenau that I would cut classes on Fridays and Mondays to teach snow skiing over the weekend in North Carolina.” From teaching at various ski resorts and learning aerials and jumps, or “ballet on skis,” Kathy started the first freestyle school in the Southeast.

“Art was not on my radar,” she proclaims. Securing a “real job” wasn’t a priority either, but her dad insisted it was time.

Little did he realize that when Kathy became a flight attendant for Delta Air Lines, she would also join the company’s downhill ski racing team. Ironically, a job relocation to Miami also gave her more time to water ski and master tricks, including the reverse toe back, performed by only one other female in the country. “I would think so deeply about it,” says Kathy, who took her ski handle on Delta layovers and practiced with it attached to a door handle in her hotel room. “In 1981, the first year I went to ski in the national tournament, I became a national champion, number two in the nation. During all this time,” she notes, “I had a strong faith. I believed my true calling was to be an athlete, so I put everything into it.”

- Before becoming a professional artist, Kathy skied for national teams on both water and snow and was a national water ski champion for women’s trick skiing, among other accomplishments.

- Before becoming a professional artist, Kathy skied for national teams on both water and snow and was a national water ski champion for women’s trick skiing, among other accomplishments.

And then she met and married Jef Fincher. “I never allowed him to talk about children,” says Kathy, who had neither the slightest maternal instinct nor any notion of altering her competitive, on-the-go lifestyle. “God has a good sense of humor,” she avows. “I got pregnant on my honeymoon.”

Honoring Jef’s concerns over safety, Kathy put both types of skiing on hold during her pregnancy and focused on tennis. “My team would make it to the state finals,” she remarks. Fulfilling her commitment, after three hours, she made it to a three-set tiebreaker but lost because of a “nagging problem.” She was in labor!

Kathy arrived at the hospital in plenty of time to have Maggie, but her concerns went beyond giving birth. When she closed her eyes, she couldn’t see herself as a mom. She saw water skis and snow skis. In a prayerful moment, she asked God if her maternal instincts would ever kick in. Of course, they did—to an extent. “I had this little baby with a squished nose and all the bonding feelings, but,” she confesses, “it didn’t take long before I was ready to go back to skiing and turn the baby over to the housekeeper.”

Daughter Kelley came soon after. With two children under the age of two, Kathy says, “I told Jef, ‘We’ll find somebody nice to raise the kids.’” Strong female voices were telling her she was a national champion; her husband was asking Kathy to be a mom.

From a Bible study on marriage, Kathy says, “I learned that it was not about my relationship with Jef, but with God.” In other words, she let go of the image she had of herself and allowed God to show her who He wanted her to be. She gave up competitive skiing. “I was miserable,” she says. “I had no identity.”

The timing was perfect for her mother and aunt, both artists, to ask, “Won’t you paint with us?” They had been studying under an artist who used dry pastels, and Kathy vividly remembers “the explosion of being able to work in color.” Also, she says, “Pastel is so spontaneous. You need a color and you pick it up. Oils, you have to mix.” Even better, she didn’t have to “paint from a bust. For the first time, I fell in love with the ability to create.” She began with impressionistic landscapes and had some in a shop for framing, where an art publisher spotted them and readily offered Kathy a contract to sell her work as prints.

A Little Help from My Friends

Although she enhanced the landscapes with “Monet-type women in long dresses, when that was the rage,” Kathy didn’t care to paint faces, much less children. Her mother, nevertheless, insisted she do a portrait of Maggie for the nursery. Her good friend Laurie Snow Hein, a renowned portrait artist, was visiting, so Kathy asked, “Will you help me do this? You paint the kid, and I’ll paint the background.”

Seeing the finished portrait in Maggie’s room, the publisher took a photo, which she sent to Current (Current Media Group). The retail catalog company, specializing in paper items, offered Kathy a calendar contract that paired her with a complementary artist, who, coincidentally, was Laurie. Each would provide six paintings featuring children. “You have a problem,” Kathy told her publisher. “I don’t paint children.” Her publisher told Kathy she painted them now because the contract was too good to refuse!

When her first illustrations showed children from behind, her publisher, wanting a face, sent Kathy back to the drawing board. Using a photograph that she’d taken of a little boy, Kathy planned to circumvent the issue by concealing his features with a hat and scarf and showing him through a snowy window. Then it happened. “I started working on the little bit of the face that was exposed,” she says, “and I immersed myself in the expression. One thin shadow around the mouth changed everything. I was hooked.”

“I started working on the little bit of the face that was exposed,” she says, “and I immersed myself in the expression. One thin shadow around the mouth changed everything. I was hooked.”

The painting, First Look, launched a body of work that has made her one of the world’s most-licensed children’s artists with collections named Mama Says®, Country Kids, Spirit of Innocence, Little Lessons in Faith, and UnBridled Wonder. Accordingly, she’s known in the art world as the “feminine Rockwell.”

In her third year with Current, Kathy accepted a significant commitment as the exclusive artist for her calendar. She approached every painting as “fine, classical art,” each taking a month to complete, and she was still flying for Delta. Remembering how she painted on the final deadline image until FedEx arrived for the pickup, Kathy says, “That’s when I called it complete!”

Demand further heightened with a Christian publisher’s book contract, and other licensing opportunities materialized in the gift industry for merchandise like figurines, bronze statues, and ornaments. Unfortunately, the relationship with her art publisher went sour, forcing Kathy to sever those ties.

All Mine | Available as giclée canvas, 24 × 18 in.

“When I left the publisher at the age of fifty, I left behind every painting I had ever done,” she says. “The company owned all the copyrights. I didn’t even have the rights to make personal Christmas cards from my art.” Losing control over “intimate images,” painted from her photos of children who were family and friends, was devastating.

Starting over, she represented herself. “I went to the licensing show in New York with twelve new images,” Kathy says. “I was on the same aisle as the publisher, also licensing my art. It made them look terrible.” Even then, buying back her rights took five years, prompting Kathy to give talks on copyrights for the benefit of other artists.

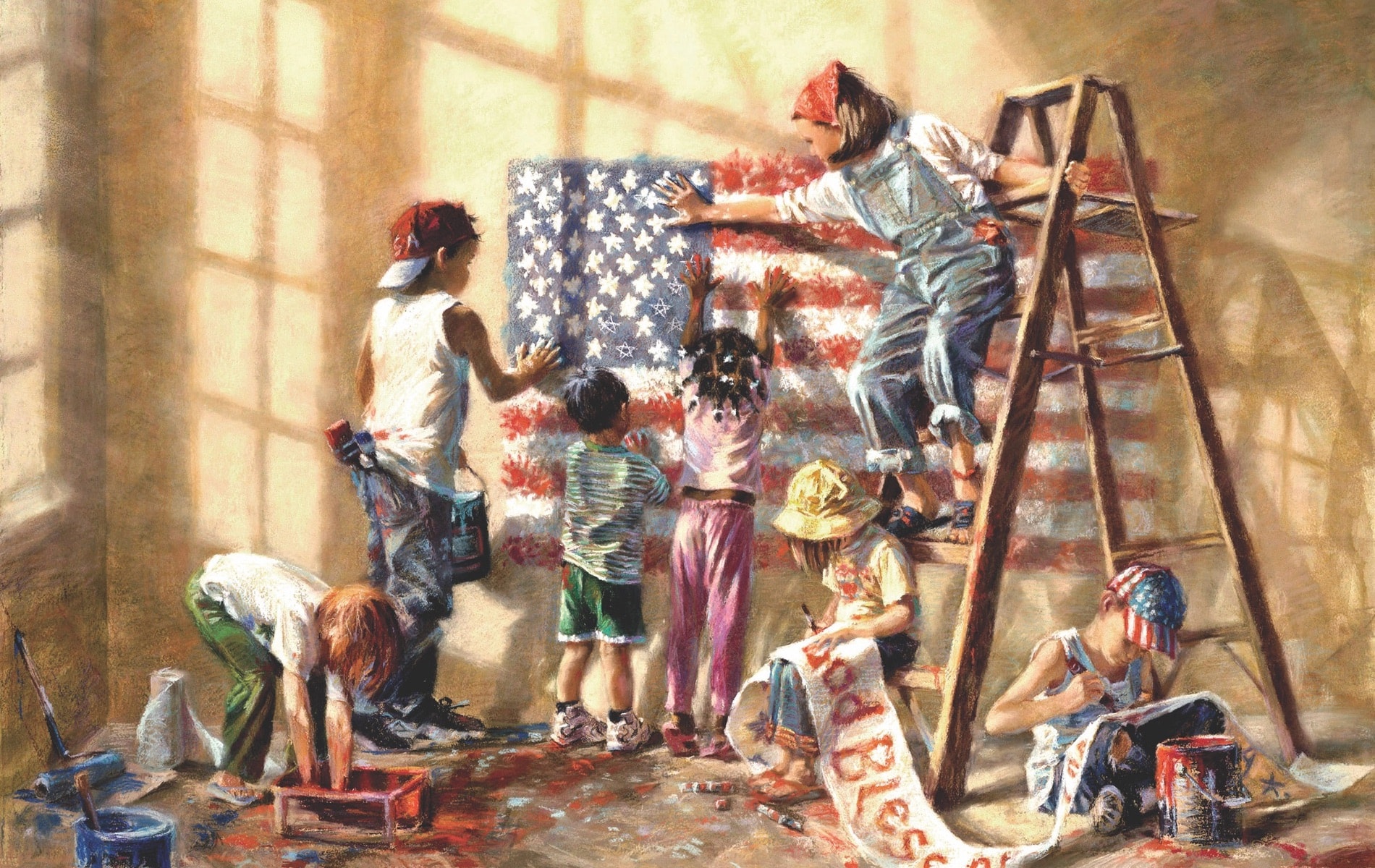

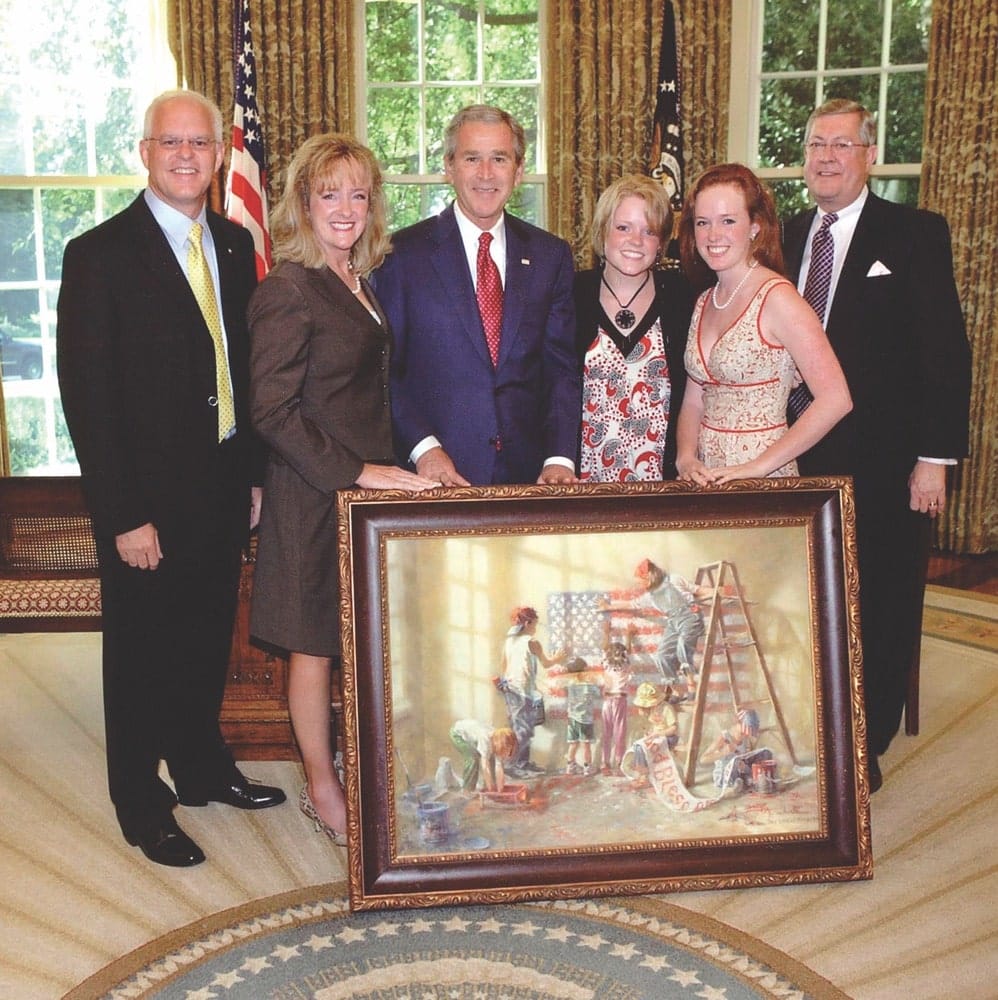

She also speaks about her faith and American values, often based on The Dream Keepers, a pastel and watercolor that Kathy painted in response to 9/11. With assistance from former Georgia Congressman John Linder, she presented the work to President George W. Bush in the Oval Office in 2007. The original now belongs to the George W. Bush Presidential Library. A monument of The Dream Keepers with lifelike bronze statues also graces the town green of Duluth, Georgia.

Artist Kathy Fincher and her family present The Dream Keepers to President George W. Bush in the Oval Office.

“The Dream Keepers was a reckoning for me after 9/11,” Kathy shares. “I realized I wasn’t meant to be a bystander.” Reflecting upon Norman Rockwell’s paintings, which “helped people remember who they were” during the World War II era, Kathy says, “I felt I had that same responsibility to give a message of hope.”

In the aftermath of 9/11, Kathy recalls, “Children were drawing buildings burning. Other artists were painting children holding flags. I stared at a blank canvas and wondered, who are we and why are we such a threat?” She landed on the pillars of faith and freedom. “I drew a rectangle to represent the flag for freedom and a cross for faith to symbolize our Judeo-Christian heritage. I thought, what if these children were dipping their hands in paint and putting their flag back together? Even more symbolically, I decided the children would put the American Dream back together.”

From a design perspective, Kathy says that adding the stepladder “to intersect all those horizontal lines of the flag” was a breakthrough. Placing the children (Jef suggested seven to represent the seven continents) on different levels and creating the arched window also enriched the composition. “It wasn’t until I came up with the idea of light streaming in from a side window that I realized it could cast the shadow of the cross to represent faith.” While in the Oval Office, President Bush, admiring Kathy’s use of light, had commented, “Light and darkness coming together made the shadow that shaped your cross. That’s what 9/11 was all about.”

“It wasn’t until I came up with the idea of light streaming in from a side window that I realized it could cast the shadow of the cross to represent faith.”

She was not envisioning anything like that moment when Kathy took her painting to the Duluth town green, where she’d find her aunt and mom, to ask them, “Is it finished?” They told her, “It’s perfect!”

A bystander chimed in, “I’ll tell you one thing, that blood-stained handprint is powerful.” The painting had many tiny hands, so Kathy needed him to point out what he saw. “The one at the foot of the cross,” he indicated. Seemingly, the children’s footprints, in and out of the red paint, had created a large, perfectly shaped hand.

“Do you know how challenging it is to draw a perfectly proportioned handprint?” Kathy says, challenging any skeptic who suggests that the hand formed by accident.

- First Look | Available as fine art print, 14 × 11 in.

- Chrysalis

Fate also had a hand in instituting the monument, officially ordained as a 9/11 memorial. Kathy was considering something for the Bush Library but decided Duluth deserved a monument. She had the epiphany in 2012 when Rand McNally (the map producers) named her hometown among America’s top five most patriotic cities.

She hadn’t sculpted since college, so Kathy commissioned Atlanta-based sculptor Martin Dawe to fashion the lifelike bronze figures from her designs. When he showed her the first child and asked her to edit the work in progress, Kathy presented a list of comments. He offered her a hand of clay. From that point on, she sculpted with him. Having hundreds of figurines made from her artwork, she says, “I’d edited sculptures—noses, ears, position of legs—almost every day for thirteen years on the computer. It was heaven to see all four sides at once and get my hands on it.”

Given her project management and fund-raising know-how, along with her artistic talents, Kathy welcomes opportunities to help other municipalities and organizations erect monuments. “I think cities should be telling the stories of their past through their art,” she says.

Guided by her faith and love of country, Kathy is currently working on a series based on the themes of Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 Four Freedoms speech: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Using a scrapbooking technique, Kathy is combining images of her paintings and photography to represent the “freedoms of,” and she’s depicting “freedoms from” in two new paintings. Contemplating Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series and channeling the maternal instincts she’s developed over time, Kathy says, “It hit me: what would those freedoms look like today, especially if done to educate children?”

— V —

To learn the answer, readers should visit KathyFincher.com to see a video of her work coming to life and to explore the paintings, prints, books, and other items in Kathy’s catalog. Numerous items are available to purchase, and Kathy welcomes inquiries about commissions and speaking engagements.

Sallie W. Boyles works as a freelance journalist, ghostwriter, copywriter, and editor through Write Lady Inc., her Atlanta-based company. With an MBA in marketing, she marvels at the power of words, particularly in business and politics, but loves nothing more than relaying extraordinary personal stories that are believable only because they are true.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE