vie-magazine-iron-pour-feature

Iron Will

A journey inside the unique world

of cast iron artistry

By Tori Phelps | Photography by Bob Brown

“You’ve gotta be a little crazy to want to get into it.”

“Physically, it’s really hard work.”

“Many times, pieces end up big and heavy; people who buy art usually

don’t want big and heavy.”

Cast iron artists readily admit that their medium is grueling, doesn’t have a huge market, and requires a touch of, well, craziness. While most people would consider these good reasons to avoid dedicating one’s life to something, this group isn’t deterred by the so-called drawbacks. If anything, the medium’s challenges only fuel their passion and encourage a deeper devotion to a relatively new art movement rooted in centuries-old craftsmanship.

The next time you visit an art museum, you probably won’t find a wing dedicated to cast iron art. Its ancestry, however, is visible everywhere, from the railing outside of the building to the bathtub portrayed in an eighteenth-century painting. Ironworking is nothing new, but what was once utilitarian has become something purely aesthetic. “This is artwork that’s contemporary but also has a historical link to it,” explains Ira Hill, a professional cast iron and cast stone artist based in Tallahassee.

In an age when many artists are employing new technologies, cast iron artists are using technology that was state-of-the-art circa the sixteenth century, says Hill. That’s because the nature of iron hasn’t changed since the beginning of time, adds Jeremy Colbert, a cast iron artist and the sculpture and ceramics facilities specialist at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. “It still has the same set of problems and the same variables. In some ways, it’s a very technical process, but it’s also as primitive as ever.”

You have to be good—really good—to work with a material that’s heated to over two thousand degrees Fahrenheit. And that’s why cast iron artists get by with a little help from their friends. Unlike other art forms, cast iron isn’t typically produced in a secluded environment. From the purely physical (needing help lifting pieces weighing hundreds of pounds) to the more philosophical (sharing advice on how to unmold rock-hard yet surprisingly brittle iron), it’s generally a group effort.

Hill and Colbert’s cast iron group includes fellow artists Scott Marini and Amy Brown; all attended the Florida State University MFA program and studied with cast iron trailblazer Charles Hook. They’re separated by geography, so between get-togethers they research new ways of doing things, build molds capable of shaping molten iron into art, and create the tools of their trade with MacGyver-like ingenuity. “Equipment is expensive,” notes Marini, an associate professor of fine arts at Albany State University. “I was taught that you use what you have, fix and reappropriate tools, and go to scrap yards to make old things new.” Case in point: Marini turned an old charcoal smoker into a cupola, which is the furnace used by casters to melt iron.

This resourcefulness is something cast iron artists have in common, along with a willingness to get dirty and an exceptional work ethic. “If you’re not up for hard work, you won’t make it in cast iron,” says Colbert. “It’s extremely grueling. The work that goes into an iron pour will blow your mind, from the mold-making process to breaking up old iron bathtubs and radiators with a sledgehammer. And that doesn’t include the cleanup process, breaking your piece out of the mold, the patina finish … it never ends.”

But this devotion to a seemingly never-ending process results in Renaissance men and women who know a little bit about a whole lot of things. If the world’s technologies were to come crashing down tomorrow, you’d better hope you know a cast iron artist who can help you survive. As Hill puts it, they just “know how to do stuff.” Welding, mixing high-fire clay for the furnace, building the furnace itself, having an understanding of concrete, fabrication, kilns—the list of “stuff” they know is similarly never ending.

Molten iron being poured from the ladle into a mold

Cast iron is a convergence point where science, knowledge, and creativity meet, which may help explain why nearly all of these artists describe it as a ridiculously difficult medium to master. Yet something about the hard, dirty, backbreaking nature of iron continues to call to them. Marini says the allure it holds for him is the ability to visually tell a story with the objects he chooses to cast. “With casting, an everyday object becomes something monumental, something timeless.”

Colbert finds the material itself poetic. Produced only during a nebula—when a star is born—iron is what runs through our veins, in a very literal way contributing to who we are. “Humans have always had a profound attraction to this mysterious metal,” he says. “Plus, most iron is recycled from something else, so you’re tapping into the energy of what it used to be, and that sometimes comes out in the work.”

Brown, who considers herself the novice of the group, says she’s constantly amazed by the level of detail she can achieve with cast iron—a result that makes the hard work well worth it. And this observation comes from a painter who can produce intricately detailed work on canvas for roughly one-millionth the physical effort it takes to produce cast iron. But some things—like the sea life and animals of her native North Florida—simply deserve the 3-D effect that is possible with iron.

Colbert doesn’t specialize in any particular subject matter, focusing instead on communication between the artwork and the spectator. He’s learned the hard way that not everything translates well. “Once people get hooked on iron, they want to cast everything in it,” he says. “But this material says something unique, and it can lose its magic when used too much. It’s kind of like profanity: if you’re cussing all the time, those words lose their power.”

Marini concentrates primarily on superstitions and folklore, using animals and animal hides to tell those stories. His latest piece, honoring the legendary view of quails as close-to-the-earth, family-oriented birds, was completed just in time for display at April’s National Conference on Contemporary Cast Iron Art and Practices at Sloss Furnaces in Birmingham, Alabama. This biennial event holds a special place in the team members’ hearts. “It’s an opportunity to get together with the cast iron family,” says Marini, “and it really is a family.”

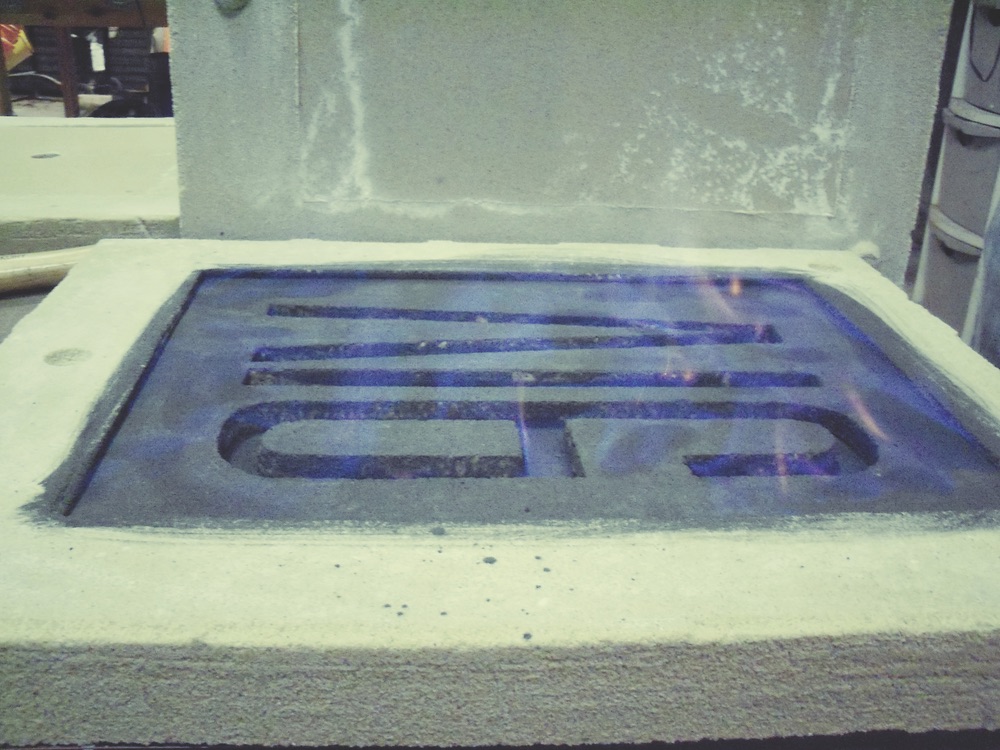

Detail of an iron casting by Amy Brown

The Birmingham conference is where many artists are first introduced to the larger cast iron community—people who, like themselves, consider smashing up and melting old cast iron sinks a good time. The conference combines panel discussions, exhibits, competitions, demonstrations, and nitty-gritty iron pours. Sloss runs its own furnaces and invites guest furnaces as well, including the one Colbert runs for their group and anyone else who wants to use it.

Even people who have their own furnaces will bring molds and participate in the iron pours, because at its heart, casting iron is a communal experience. “If I wanted to pour a piece or two by myself at home, it can be done,” Colbert says. “But you’re wasting a lot of fuel by doing that, and it seems really selfish not to share your resources. It’s like firing up a jet just to fly around town.”

There’s no proprietary feeling about processes or in-progress pieces for cast iron artists; they want to pass on what they’ve learned, especially to the next generation of artists. And there will be plenty of these young artists at the Sloss conference, which just keeps getting bigger and better. Part of that has to do with the venue. Beginning in the 1880s, Sloss Furnaces produced iron for almost a century, birthing an industry that gave rise to the city of Birmingham. Sloss is now a National Historic Landmark and museum, dedicated to preserving the culture of cast iron. For many cast iron artists, coming to Sloss is like making a pilgrimage to the motherland.

Scott Marini in full leathers and gear

Mostly, though, the conference is about connecting with old friends, making new ones, and the thrill of displaying work to an appreciative audience. “What I love best about cast iron is the moment when your piece is all cleaned up, reads the way you want it to read, and people are lit up by it,” shares Colbert.

The worst? “Everything before that point,” he laughs.

All of them echo the same reality: The physicality of cast iron work is an ever-present challenge. It’s not unusual for people to injure themselves with all the heavy lifting required—sometimes even seriously. And the technical side isn’t any easier. Castings go wrong all the time, Marini shrugs, noting that disappointments are just part of the process. But when disappointments happen, this tenacious crowd comes back for more. “I’ve got one mold I’ve tried to cast five times without success,” Colbert says, “but damned if I don’t have that mold waiting for a sixth try.”

Heating up the cupola

Considering the amount of work that goes into a finished piece, it’s easy to understand why the artists bristle at the word “hobby.” Though not a profession for most, nearly all consider cast iron to be a lifestyle and a very meaningful part of who they are. It’s my art, they repeat, accepting that within those three words are frequent pain and frustration—things most of us run from, but which they willingly run toward. “The truth is that you sweat for it, you bleed for it, you cry over it, and you take copious amounts of Aleve because your body hurts,” Colbert says. “It’s a huge challenge. But if it came easy, you wouldn’t appreciate it as much.”

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE