vie-magazine-stefan-hands-and-lives-feature

Give Him a Hand

By Rick Bennett | Photography by Stefan Daiberl

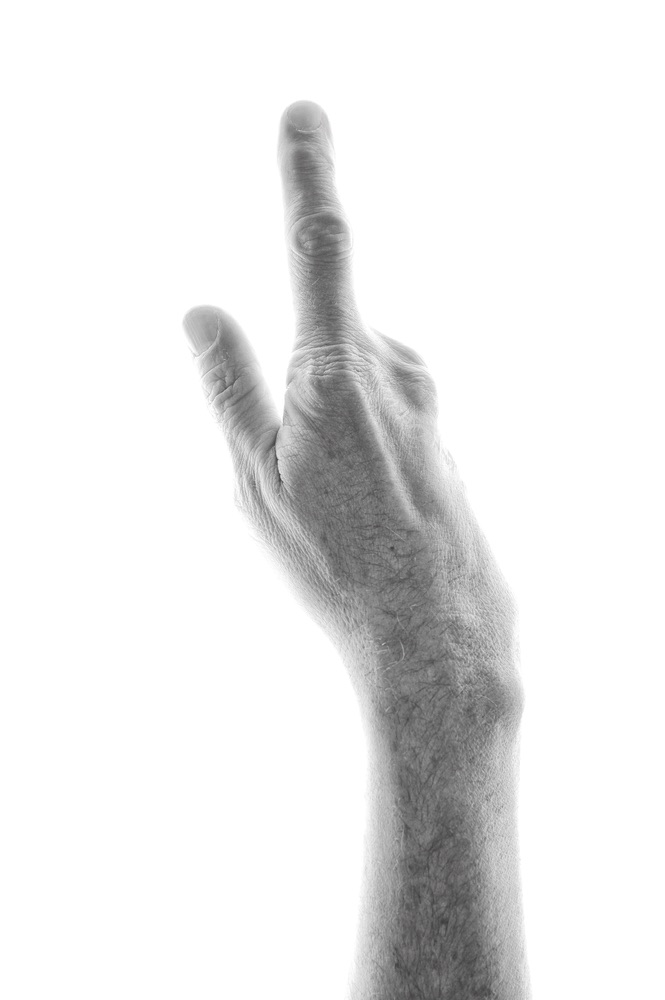

The art of photographing the human body is as old as the camera itself. Art books and advertisements overflow with images of mouths curved up in half smiles, graceful silhouettes of bare backs, and powerful dancers’ legs in motion. But Stefan Daiberl has found his muse in the humble, often-overlooked hand. For the past year, he’s been consumed with photographing hands: old, young, wrinkled, smooth, scarred—he finds a story in each of them. It’s a project that started with a simple handshake but has taken on a life of its own, inspiring confidence in the timid and even comforting the bereaved.

Although he was on the hunt for artistic inspiration, Daiberl was surprised to find it in Sid, a maintenance worker at WaterColor Resort and Inn in Northwest Florida. When the two shook hands, Daiberl was overwhelmed by the sheer size and power of the man’s grip and immediately began wondering about the physical labor that had shaped it. “I realized it was a recording of this guy’s life up to now,” he says.

Sid was a bit taken aback when Daiberl asked to photograph his hand, but he agreed to be an artistic muse. That led to pictures of other WaterColor workers’ hands, and soon Daiberl was asking strangers if he could snap a quick photo—not always an easy sell. “People get freaked out when you want to photograph their hands,” Daiberl says. “They think I’m either a pervert or from the FBI.”

He’s neither, of course. He’s an artist, and perhaps an unexpected one at that. German-born Daiberl, who earned an MBA after moving to the United States in his twenties, was on the fast track to success as a management consultant in Manhattan. Then came 9/11. He decided to trade the chaos of the city for the more laid-back lifestyle of Florida, first opening a successful interior design firm and then opting to concentrate on his growing love of art.

His urge to create manifested when his life seemed to be falling apart. Soon to be divorced, Daiberl was out for a walk and stumbled upon a copse of burnt trees. He was gripped by a desire to make something out of the blackened wood, in a very real way putting his own world back together by salvaging something left for dead. His materials were admittedly dark in the beginning—ammunition and syringes, for example—but he eventually moved into beautiful sculptural work, including the illuminated spheres for which he’s best known.

Until the Hands and Lives project, that is.

At forty-three, Daiberl has started thinking about his own life—where it’s going, where it’s been—which inspires similar questions about the people he meets. He wants to know their stories, which, for him, starts with their hands. And boy, has he heard some stories. There was the woman who wore a ring made from the melted gold of both her deceased parents’ wedding rings. There was the man who, due to an accident on a riding lawn mower at age seventeen, was missing three fingers on one hand. Once so ashamed that he bandaged his hand before going out in public, he bravely allowed Daiberl to photograph that hand, which Daiberl described as “beautiful, like a flower.”

And then there was the handsome, vital nineteen-year-old who died in a car accident four months after Daiberl photographed his hand. As Daiberl made prints of those photos for the young man’s grieving mother, he realized Hands and Lives offered another, unexpected dimension. “I have these records,” he says with awe, “and while the subjects will all be gone one day, the pictures will still be here.”

He hopes the collection ultimately will include famous people he admires—mostly musicians such as Robert Smith, Tom Waits, and Icelandic singer Jónsi. He stresses, however, that you don’t have to be famous to make it into the Hands and Lives project. All you have to be is willing.

Daiberl feels indebted to the people who’ve already lent him their hands—many of whom become emotional when revealing stories about the jewelry they’re wearing or what their hands have been through. “It’s a very personal thing,” he explains. “Imagine all the things people do with their hands: pat their kids’ heads, eat with them, make love with them. It’s an honor to capture that with a picture.”

He’s made the collection public at HandsandLives.com and will give art lovers a chance to view five-by-four-foot versions of the photos at a gallery show this fall in either New Orleans or New York City. He also intends to create a book featuring some of the photos and the accompanying stories about the people behind the hands. Daiberl is in no rush to complete the book, however, saying he wants it to be done right rather than done quickly.

Besides, he has more pictures to take.

“Someone once said it takes ten thousand hours to master a skill,” Daiberl says. “Maybe it will take me ten thousand hands to capture the full story of humanity and, with that, to understand life.”

— V —

For more information about Hands and Lives or to become part of the project, visit HandsAndLives.com.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE