vie-magazine-san-francisco-hero

San Francisco, California, has long been known as an artistic capital in the United States, especially as part of the 1950s and ’60s beatnik and hippie cultures. Today, the growth of the city as a technological hub of the world has forced shifts in the art scene, but the Bay Area remains a mecca for artists, writers, and musicians.

Dirtbag City

Art and Artists of San Francisco

By Lizzie Locker

“It’s hard out here for a pimp,” I croak. My roommate Nikki giggles as she stirs her coffee over the sink. She drags the wet spoon across her paint-splattered hoodie absently, the same way she wipes her paintbrushes. Her eyes are puffy, her blond ringlets wild.

I am usually at our kitchen table at seven in the morning, bent over my laptop or my sewing machine, hammering away at some unimportant project I wish I could call art. Nikki’s hoodie, its front covered in streaks of coordinating blues and grays, is more worthy of the title. We are both getting ready to go to work (not our real work, you understand, just the work that pays us)—me to the couture fabric store where I’m little more than a shopgirl, she to run errands as a personal assistant to a local entrepreneur. I’m worn down from saying the same things all day, climbing ladders, lifting heavy stock, fetching, finding, matching, and measuring for the clueless or the color blind. When all that is done, I’ll come home, light a joint, turn on Netflix, and allow myself to dissolve. That is the kind of “artist” I am.

Nikki, though, is not. When she is done with work, she will go to her studio in the shipyard to paint. She will build frames, stretch canvases, and splatter and splash paint until the wee hours of the morning. She does her real work in the quiet of the night while I am fast asleep with the television leaking canned laughter and blue light. “Gotta get your forty hours in somewhere,” she says to me all the time. Most people don’t get the joke—that her forty-hour workweek only counts hours painting, not PA-ing.

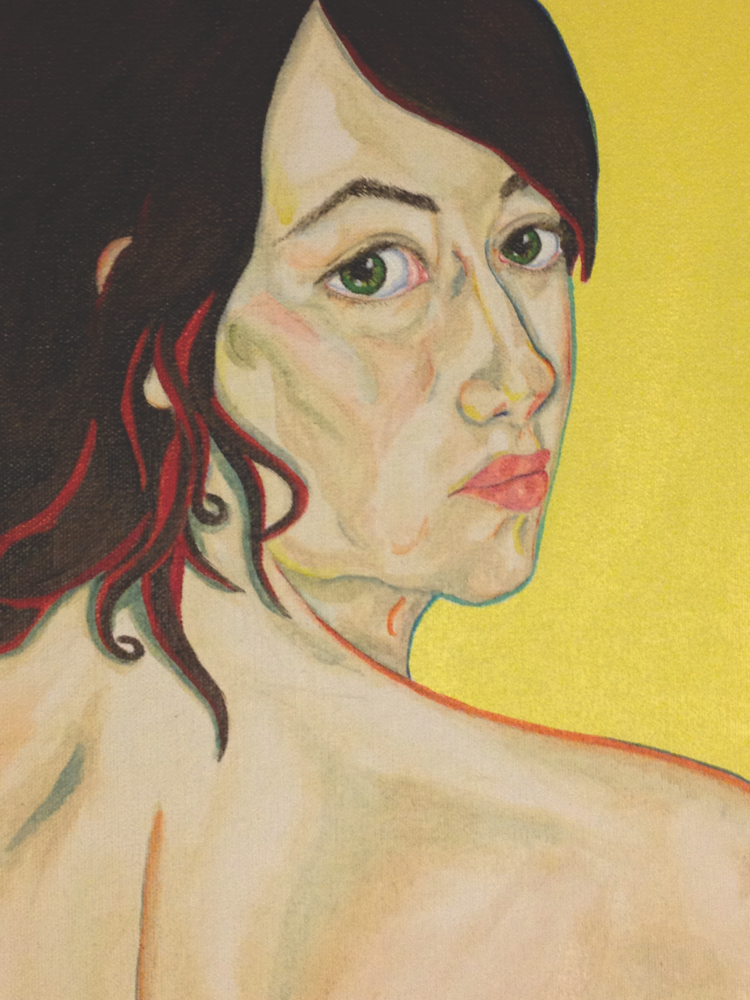

Nikki Vismara is a graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and has a master’s degree from the University of Lyon in France. She has a studio at Hunters Point and currently serves on ArtSpan’s Open Studios committee. NikkiVismara.com

Nikki Vismara, my roommate, is the real artist. She’s the one you’ll remember in a century, the great painter and party princess. When I tell you, I tell you truly, she is a hustler supreme and queen of the scene, from the loud and crowded hip-hop underground of Oakland to the wine-and-cheese rooftop soirees of LA. She’s the type of unforgettable, undeniable force you won’t forget: “that girl with the hair.”

I tell Nikki she looks tired, and that maybe she should go back to bed and go to work an hour or two later since she has that luxury.

“Motivate, don’t marinate!” she chirps, shrugging her sharp shoulders, grinning her bitter grin.

We’ve been flocking to San Francisco forever—the weirdos, the freaks, the wicked, and the wild. We came with the Gold Rush and never stopped. When what you do or what you are becomes illegal, you come to the Sanctuary City, where it seems like no one is illegal and nothing is not allowed. San Francisco is where outlaws come to find shelter, where refugees and immigrants come to find a home, where long-haired children come to get high and enlightened, where those with leather-clad longings find the key to their release, where the weird come to be left alone—and where everyone else comes to strike gold.

I came for lots of sad and desperate reasons, but all you need to know is that I came to get a master’s degree at the University of San Francisco. I came to be a writer, an academic, an artiste of the champagne variety.

I hoped.

While many artists struggle to stay afloat and navigate the changing environment in San Francisco, the city remains a tourist destination chock-full of museums, galleries, public art displays, and other cultural centers.

I arrived in the city with my cat under my arm and one good dress, with no job, no place to live, and no friends. I landed in a one-room apartment with a shared bathroom (for which I paid $1,300 per month) in San Francisco’s infamous inner-city human litter box, the Tenderloin. I survived on cheap wine and cheaper Korean fried chicken from the shoebox-sized restaurant next door, and I spent my nights drinking overpriced Bud Light at Diva’s, the transgender dive bar across the street where no one bothered me in my back corner booth.

Those early, grungy days still reek in my mind—waking up to acidic, merlot-purple vomit in my sink and not remembering how it got there; playing a wry game of “Human or Dog?” with myself whenever I passed glistening feces drying in the hot summer streets; dodging needles in the gutters; breathing in the cloudy stench of mold in the basement of my apartment building, where unwashed folk occasionally snuck in and camped behind the washing machines.

At the same time as all that, I led a second, much sweeter life. In my MFA classes I was the social butterfly who got everyone out to the bar after class, the bright and excited voice that charmed my professors. I got a job at Britex Fabrics, where I received a box of chocolates and a handwritten thank-you note from the designer who was working simultaneously on Steve Jobs and the original Broadway production of Finding Neverland. I pretended to be a brilliant academic and a truly exciting talent as a design consultant to the stars—while living in a single room and sleeping on the floor.

All this is to say that the San Francisco’s art scene is as dual-natured—or deceitfully natured, perhaps—as your humble narrator, if not more so.

There are, of course, perks to being an artist in the city—lots of them.

Carrie Sheppard is a painter and writer with a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MFA in creative writing from the University of San Francisco. She lives in San Francisco where she is currently at work on her first novel. Carrie is on Twitter @C_Sheppard007.

Carrie Sheppard is a writer and talented painter from the cohort that followed mine at USF. She submitted her thesis, a novel, in December, and recently she’s been able to devote a bit more time to painting. Her current series is full of literary inspiration. My favorite is a portrait of a stag dressed in drag with pearls and spectacles, inspired by Jane Austen’s style and snark.

Carrie lived in New York City for several years before moving to San Francisco, and as we stroll down Larkin Street after Sunday brunch, she tells me that in many ways, “It’s better here than in New York. You can have more actual space here. And you can approach people.”

As an example of this, she cites a bit of departmental gossip: another member of her cohort met novelist Marlon James in the bookshop where he worked and considered asking James to join him for a drink after his shift. He didn’t, and regrets it, because as Carrie says, “James might have actually gone with him, because here, he would probably have had time. You don’t have that in New York—and New Yorkers just won’t approach those kinds of people.”

Nikki agrees. “It doesn’t always feel like a big city here,” she says. “Things are accessible here; there are a lot of niche markets, niche scenes. We all know everyone.”

San Francisco has always been where outlaws came to find shelter, where the weird came to be left alone,where everyone else came to strike gold.

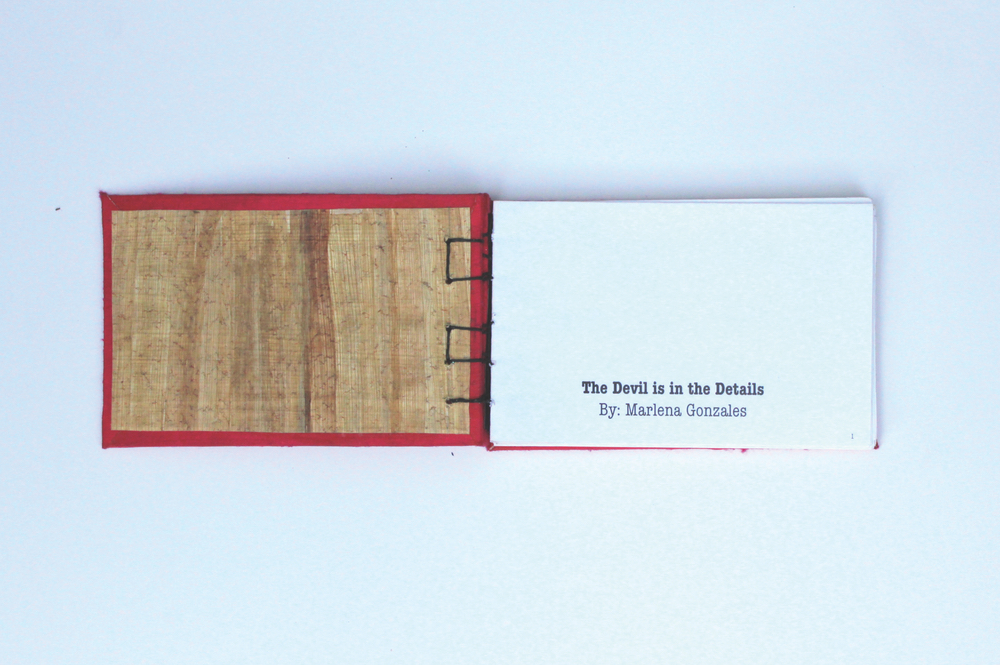

Marlena Gonzales is a fresh-faced, bubbly furniture designer with a passion for community involvement and development. She graduated from California College of the Arts a few years ago and now works as a prototype creator for a toy company. She also writes and illustrates craft tutorials for DIYers and hopes to be a design educator in the future. Marlena’s art is meant to be shared with others; that’s why living in San Francisco is important to her as an artist. “Overall, I love the diversity of the community I live in,” she says, “and I feel so happy to be a part of it. I’m learning so much living here.”

Ask any artist in the city what their greatest struggle is and they’ll all agree on one thing: housing. You’ve heard my story of high rent and low standards, and too many others have similar tales, but there are far worse ones.

Marlena Gonzales was born in Austin, Texas, and received her BFA in furniture design from California College of the Arts. She currently works as a toy and packaging prototype creator for University Games. MarlenaGonzales.com

You may be familiar with Ghost Ship, a warehouse in Oakland, just across the bay, which was poorly converted into an artist collective and dwelling. Last December, thirty-six people died tragically in a fire that broke out during a concert at Ghost Ship. In the aftermath, authorities discovered numerous safety code violations, such as a lack of smoke detectors, sprinklers, and emergency exits. Permits for the concert were never filed. Blame was assigned first to the victims themselves (“They should know better than to try and live in those spaces!”), then to the building owner, and even to the local building inspectors.

The root of the problem is much deeper. With water all around us, we cannot sprawl outward like most cities, and rent is so high that decades-old institutions such as Jeffrey’s Toys, Xanadu Gallery, the Gold Dust Lounge, and the Stud have all been pushed into new spaces, new ownership, or out of business entirely. These were successful businesses for many, many years, with money and reputations to protect them. But if retail royalty such as Macy’s can’t even justify paying the rent on its Union Square location (as rumor has it), is it any wonder that we desperate dirtbags find ourselves living in such inhospitable spaces?

But artists are everywhere in this city and art has been reduced to a side hustle. If it’s not making you money, it’s regarded as a hobby that’s not really to be taken seriously.

My friend Lydia—it isn’t her real name, but for her protection, I’ll call her that—lives in a precarious situation. A burlesque dancer of immense talents, she has struggled for nearly a decade to find permanent housing in the Bay Area. After a nightmare series of sublets and letdowns, she finally found an ideal space that she could afford, another warehouse converted into a live-and-work space for artists. After the Ghost Ship tragedy, building code crackdowns sent Lydia and her fellow denizens scrambling. Though the owner of their building was okay with tenants living in the space, Lydia and her fellow artists were worried about what the inspector might discover. A single violation could evict them all from their hard-won homes, so they made their living spaces to look like studios or rehearsal spaces and vacated the premises for a while. “We can’t be seen leaving the building in the morning,” Lydia told me when she asked to crash with me for a night. “It’s just a big risk.”

It’s a catch-22 situation; to protect people, we must keep them from living in dangerous situations, but if we prevent them from living in one dangerous situation, they might be forced into one that’s even worse.

Housing isn’t the only problem; the art scene itself is homogenizing. To appeal to the mainstream appetites of San Francisco tech workers and tourists, the avant-garde scene that the city became infamous for in the 1980s and ’90s is slipping away.

Eric Mueller, an essayist who reads his work aloud in a voice that’s as rough and sweet as whiskey and honey, is attuned to the social dynamics of the shift in the city’s art scene. Eric is the Ilana to my Abbi, the Jack to my Karen; we spend as many of our Sundays as possible on the grass in Dolores Park, drunk on warm five-dollar champagne and whining about our writerly woes as we watch all the pretty boys strip to their underwear in the warm sun.

You have to make a lot of sacrifices with a business. What are you willing to do that others won’t do?

When he moved here from New England, Eric says, “I was immediately surrounded by other writers, people who were curious to know what I was writing about. Everything about the landscape of this city stimulates my mind in ways I cannot articulate. But artists are everywhere in this city, and art has been reduced to a side hustle. If it’s not making you money, it’s regarded as a hobby that’s not really to be taken seriously. When I tell people I write, it is often returned in some form with, ‘Oh, a creative writer.’ Creative can sometimes feel pejorative.”

Eric doesn’t lie. A burning memory comes to mind of a man I thought I loved, who told me that there were two types of people in the world: makers and consumers. He, an entrepreneur, was a maker, and I, an artist, was a consumer. “You don’t contribute anything to the world,” he said to me. “Nothing of value, anyway.”

We artists have all had people we thought we loved tell us that our world-shaking and world-building was stupid or useless or evil. Or something. That’s why we came here. And yet, even here . . .

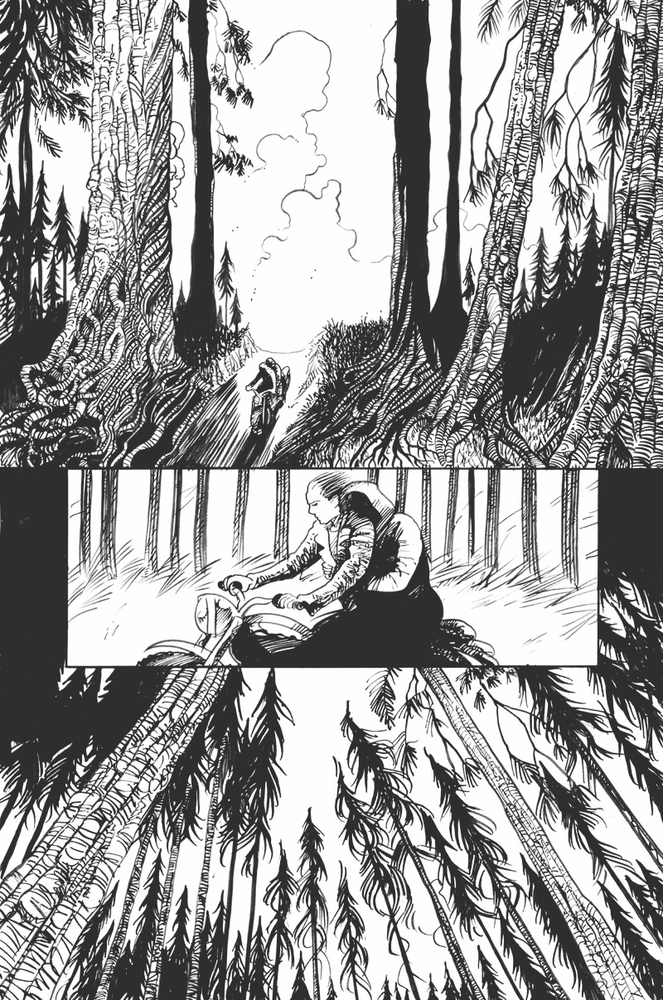

Jon Macy is a queer cartoonist who has contributed to queer anthologies such as No Straight Lines, QU33R, and The Shirley Jackson Project. He edited Alphabet: The LGBTQAIU Creators from Prism Comics, which benefited the Queer Press Grant. John lives in feisty Oakland, California. JonMacy.com

Jon Macy is a longtime fixture in San Francisco. A writer, editor, and illustrator, he’s the deviant brain behind the award-winning gay erotic graphic novel Teleny and Camille, as well as numerous anthologies. His latest collaborative project, a coloring book showcasing queer heroes such as Grace Jones and Edward Gorey, has garnered much local excitement.

“It was a good run while we had it,” he says cheerfully, belying his deep distaste for the current state of affairs in the city’s art world. “Nothing was too extreme or experimental for San Francisco. We prided ourselves on our excess. Gender, sexuality, and body politics have always been the main focus of art in SF. But politics apparently only affect the poor—” Jon can’t help smirking innocently, “—so our new art scene is careful not to offend.”

Careful not to offend the money, he means—the young techies making bank and spending it on the artisanal rather than the artistic—on craft cocktails with twenty-dollar price tags or niche fitness and diet routines. Millennial attitudes, in general, shift away from their parents’ idea of acquiring things and toward acquiring experiences. In a way, it makes sense; the physical objects associated with the arts—such as books, sculptures, and paintings—are not in demand, but skydiving selfies and snowboarding lessons are. Even on salaries that make a $3,000 monthly rent check seem trivial, according to Nikki, “Techies don’t buy art.” At least, the young majority of the workforce doesn’t. She says, “Tech workers who are maturing, who’ve been doing it ten years—they’re starting to collect.” She shrugs. “Even without tech, there’s a lot of money in SF.”

Nikki would know. She’s at the point in her career as a painter where I can see the balance tipping; she’s moments away from being the star of the hour in national, if not international, circles. She’s got an off-site exhibition coming up with Oakland’s SLATE Contemporary, and she’s working on a show with Philip Bewley of DZINE Gallery. I’ve seen Nikki’s work undergo a shift in the last year from colorful, impressionist-infused realism to dramatic, dreamlike abstract works. Meanwhile, her goals have also changed. She’s curating a sort of luxury brand, working with high-end interior designers and consultants to create custom works that decorate multimillion-dollar homes—“big paintings to match big sofas in big houses,” as she puts it.

Nikki’s a finely tuned machine of ambition, education, charm, and talent. But she’s also got a firmer grip on the professional demands of her work than many dreamers and artists do. “I think of myself more as an entrepreneur owning my own business,” she says. “You have to make a lot of sacrifices with a business. What are you willing to do that others won’t do?”

This question troubles me only because I’m not sure I know how to answer it.

It’s been a while since the miserable days that began my life in San Francisco. I live in a house in Bayview now, the last stop before the city limits cut us off from the rest of the peninsula. My bedroom is larger than my Tenderloin apartment, and I pay less for it. I’m designing and writing, and slowly I’m finding a voice people are willing to listen to. Like Nikki and I are always saying, it’s hard out here for a pimp. But it gets easier.

What You Know, You Know (demand me nothing) by Nikki Vismara, acrylic on canvas

A long-haired older man of my acquaintance says that San Francisco has always been a harlot, selling herself to the highest bidder. He says she belonged to the prospectors during the Gold Rush, then to the nobs of Nob Hill, the military during the World Wars, the gay community during the 1980s, and so on. Now she belongs to Big Tech—to Google, Facebook, and Twitter.

San Francisco is a different city now from what it was when I moved here not even four years ago. I suppose that’s part of a good prostitute’s charm, isn’t it? Her ability to transform to meet her client’s desires. Her duality is her bread and butter—to be both there with her client and perhaps somewhere else, too—to be someone’s fantasy yet still entirely herself.

This city I love so well isn’t just dual; she’s polar opposites drawn tightly into one being. She is a beautiful, coked-out queen of the corner hookers whose gender is more fluid than her body and can be anything you want her to be, but only if she agrees. On Monday, she whispers in my ear that she loves me, will take care of me, will make me a star. On Tuesday, she stabs me in the back and tries to kick me out to Oakland or Daly City or wherever she banishes those who have lost her favor. And her mood swings, her meanness, and the Sisyphean struggle of staying with her, of surviving her, only make me love her all the more.

I just sit down at my kitchen table and hammer away until she loves me back again, somehow.

—V—

Lizzie Locker is a writer, instructor, and costume designer in San Francisco. She received

her MFA in writing from the University of San Francisco, where she was also awarded

a teaching fellowship. Lizzie is currently at work on her first novel.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE