vie-magazine-jim-shirley-beard-event-hero-min

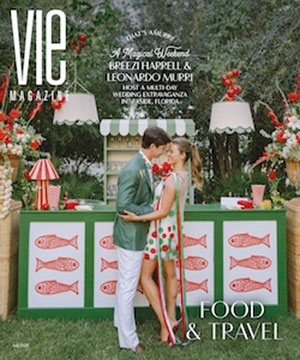

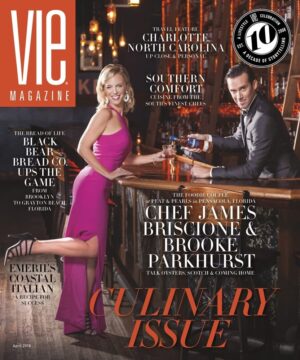

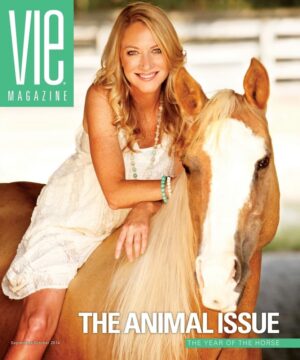

Chef Jim Shirley of Great Southern Café in Seaside, Florida, plates a delicious meal at the James Beard House in New York City on January 24, 2018.

Coastal Food with New Urban Soul

By Boyce Upholt | Photos by Kreg Holt Photography

They might not know it, but many people around the world have become familiar with classic Florida Panhandle architecture. That’s because the town of Seaside is now a global icon of good design and has many faithful imitators. Classic Florida beachside construction has influenced the standard look of New Urbanism.

The food of the region, though, is less well known. Sure, everyone eats seafood stews and fresh oysters—but fish throats? Or swamp cabbage? Even some locals overlook these classic Panhandle delicacies. Then again, before developer Robert Davis conceived of Seaside, its now-famous home styles seemed to be fading too.

Chef Jim Shirley’s recent splash in New York City could help change the reputation of these forgotten foods. On January 24, Shirley and staff from his Seaside-area restaurants prepared a five-course “Taste of Seaside” dinner at the James Beard House. The facility is owned by the James Beard Foundation, one of the premier culinary organizations in the world. An invitation to cook there—or perform, as the foundation puts it—is considered recognition of excellence. (This was Shirley’s fifth time cooking at the house, though his first as the sole headliner.) For his performance, Shirley aimed to show off the depth of Gulf Coast cuisine—and its endless possibilities.

- Dishes served at the Taste of Seaside event included a Great Southern favorite, fried green tomatoes, with a twist—kimchi to top them off.

Shirley’s playfulness as a chef is revealed in his trademark shrimp-and-grits recipe, which he served at the dinner. He stumbled upon the recipe while visiting his daughter in Italy; unable to purchase grits or bacon, he went with the local equivalents—polenta cakes and pancetta. Another hit in New York was his cioppino, a fish stew. “Blue crabs and local tomatoes—that makes an incredible broth,” Shirley says.

An invitation to cook there—or perform, as the foundation puts it—is considered recognition of excellence.

From “Ol’ Florida mullet,” as Shirley calls the familiar Panhandle fish, the chef conjured a smoky dip that was served atop house-made crackers. The dish reveals the importance of knowing your ingredients: because mullet is a bottom-feeder, it often tastes muddy. “From most places, it tastes terrible,” Shirley explains. “But you can go through the state and see where they have those clean white sands.” Those sands produce a much cleaner tasting fish. “Good smoked mullet dip is just a Gulf classic,” Shirley says.

Grouper throats perhaps best represent the more esoteric Gulf food traditions. Long eaten by fishermen, this is a delicacy unknown by even locals who have a slightly more distant relationship to the sea. Shirley compares the throats to the dark meat of a chicken, more richly flavored than the rest of the fish. He served them in a gougère (a high-class cheese-puff pastry, in other words) topped with local pickles.

Shirley knows he opened the eyes of attendees at the James Beard event. “I’m pretty sure they had not seen kimchi made of swamp cabbage,” he says, using the colloquial name for sabal palms. The hearts of new sabal fronds have a cabbage-like texture.

The son of a Navy pilot, Shirley was born in Pensacola, Florida, where he was exposed to the cultural gumbo that marks Gulf Coast food history: local Native American roots and influences from the Spanish and French empires, as well as from African chefs. The Navy influence also meant Shirley grew up eating food from across the Pacific Rim.

When he opened his first restaurant, Madison’s Diner, in Pensacola in 1995, Shirley struggled to buy local produce from farmers. “I couldn’t get them to grow anything besides squash and zucchini,” he says, “even if I gave them the seeds.”

Chefs Andrew Dahl, Tim Plowick, and Sandor Zombori of Great Southern Café and Michael Mix and Ben Steeno of The Bay joined Shirley to prepare the meal at the James Beard House.

Over time, through mutual connections, Shirley struck up a good relationship and shared a vision with Robert Davis, the founder and developer of Seaside. The town was more amenable to his explorations, given its emphasis on building sustainable, locally rooted communities. In 2006, the chef opened his first restaurant in the area, the Great Southern Café. Since then, Shirley has opened three more restaurants in and around Seaside.

Shirley says it was a bit of a scramble to prepare for the James Beard event, which was not confirmed until November. But, hoping for such an opportunity, he had planned ahead by canning and preserving local produce. In late January, his local Seaside purveyors packed coolers and wrapped them in tape—pieces of the Panhandle were heading north to the big city. One can imagine that, as the world comes to know these coastal food traditions, it won’t be the last such journey.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE