vie-magazine-chaz-davis-hero-min

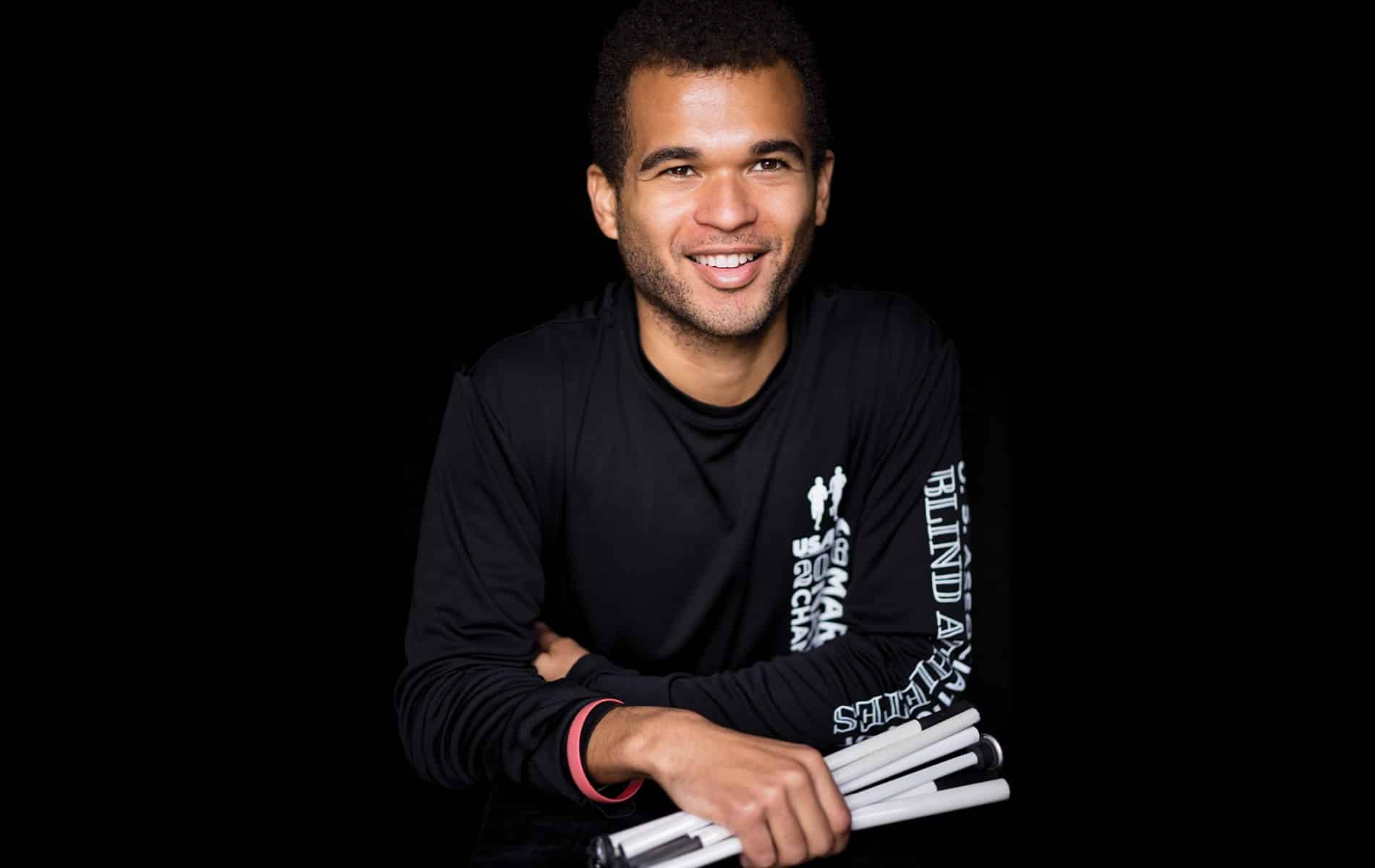

Olympic runner Chaz Davis | Photo © Robert Houser 2020. All rights reserved.

The Heart of an Olympian

Keeping His Dream Alive against All Odds

By Tori Phelps

When elite runner Chaz Davis went blind almost overnight, his new vision included the world’s biggest athletic stage.

It was something he’d done hundreds, if not thousands, of times. Climbing into the driver’s seat on a hot July day, nineteen-year-old Chaz Davis backed out of his driveway and into what should have been a familiar landscape. Except he couldn’t see what he’d always seen. Even seven years later, he vividly recalls pulling back into the driveway with a heavy heart. “That was the last time I drove a car,” he says.

By any measure, Chaz had been living a charmed life. Growing up with a younger brother and both parents in the small town of Grafton, Massachusetts, he was a gifted distance runner who, by his junior year of high school, was divisional state champion in the indoor two-mile event. He and running pal Bryan Quitadamo were roommates at the University of Hartford and teammates on the track and cross-country teams, where Chaz continued to rack up impressive performances.

In March of his freshman year, however, everything changed.

Chaz Davis competes with a guide in the 4×400 meter relay at the 2016 FloTrack Beer Mile World Championships in Austin, Texas. | Photo by Scott Strance, courtesy of Chaz Davis

He was battling a headache in class one morning, assuming a late-night study session was to blame, when he absently rubbed his right eye. Suddenly, he couldn’t see out of his left eye. Still hoping his symptoms were the result of short sleep, Chaz left class and took a nap. However, the vision problems remained after awakening, so he called his mom and soon was scheduled for a battery of tests. The diagnosis: Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), a rare disease that destroys the optic nerve.

He managed to finish his freshman year, squinting and straining to make out the text on his finals with one eye almost completely blind and the other close on its heels. In a shatteringly small time frame, he had gone from better-than-perfect 20/15 vision to legally blind. And it was almost more than he could bear.

In the darkness that blanketed not only his eyes but also his heart, Chaz fell down a rabbit hole of compulsive eating and substance abuse. The highly disciplined athlete gained sixty pounds within a matter of months and welcomed the oblivion that drinking and drugs promised—coping mechanisms Chaz doesn’t endorse but, admirably, refuses to omit from his narrative.

In a shatteringly small time frame, he had gone from better-than-perfect 20/15 vision to legally blind.

The six-month spiral ended someplace he never imagined he’d be again: the finish line. He had agreed to participate in his hometown’s annual five-mile road race, a competition Chaz had won in high school and whose profits that year were dedicated, in part, to LHON-related research. He didn’t set any records that day, yet it’s among the most memorable races of his life. Bryan and a second roommate and friend, Rourk Marlow, served as Chaz’s unofficial guides, and the three finished arm in arm. “It was pretty powerful,” Chaz says. “That was the moment I decided to get back into running.”

He didn’t think it would be easy to resume his running career. And he was right. He fell off the treadmill more times than he cares to remember and, essentially, started from scratch in his physical conditioning. Thankfully, hard work had never bothered Chaz. To ensure his motivation didn’t waver, he set a goal that was ambitious even for a decorated runner like Chaz: qualifying for the Paralympic Games two years away. The grit he needed to return to running shape spilled over into every area of his life; he lost the weight he’d gained, left substance abuse behind, and even competed at the divisional level again. But his performance wasn’t on track for the Paralympics.

Chaz Davis and Michael Wardian representing the Massachusetts Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired at the 2018 Boston Marathon as part of Team with a Vision | Photo courtesy of Chaz Davis

Then he met Roger Busch.

The new head track and cross-country coach at the University of Hartford during Chaz’s senior year, Coach Busch didn’t give the blind runner any breaks when it came to training. Chaz didn’t understand how he was going to run the cross-country terrain, but he trusted the new coach, who ultimately became a transformative part of resurrecting his running career. “The fact that he treated me as he would any other athlete and had a lot of confidence in what I could do gave me confidence,” he says.

Steadfast friends were also key. Knowing Chaz didn’t like asking for help, pals like Bryan and Rourk stepped up without being asked. Rourk ran with Chaz every day for months on end, their strides synching as Chaz blasted past goal after goal. In recounting his memories of that time—like feeling Rourk’s arm thrown out across his chest, as a mother does in a car, every time a car pulled into their path—it’s clear that those runs restored him emotionally as much as physically.

“The fact that he treated me as he would any other athlete and had a lot of confidence in what I could do gave me confidence.”

Chaz was back. Faster, stronger, more focused than ever—and headed to the 2016 Paralympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Despite a paperwork snafu that left him without a guide for the 1,500- and 5,000-meter races, he says competing in Rio was everything he dreamed it would be. Here, he wasn’t “the blind runner.” He was simply a world-class athlete who happened to have a physical disability, just like everyone else around him. As for the races themselves, the thrill of running in front of eighty thousand people is still fresh in his mind. “It was so loud in the stadium that I couldn’t even hear myself breathing,” he laughs.

He hopes to experience that feeling again at the Tokyo Paralympic Games, now rescheduled for 2021. Though he may try to qualify for a couple of track events, Chaz is most focused on the marathon. He competed in his first marathon after the Rio Games—setting the American record for his division—and immediately got hooked on them. Running on a track is pretty much the same whether you’re in Boston or Botswana, he explains, but marathons are tactical affairs that require not only stamina but also an ability to navigate different course profiles.

The 2020 Boston Marathon was supposed to be the qualifying event for Tokyo, but its cancellation in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic has muddied the road to Tokyo. Even so, Chaz continues to train. At his peak, he runs about ninety miles a week, making it difficult to find volunteer guides. The situation became even trickier when COVID-19 quarantines began, understandably prompting many guides to temporarily opt out of the job. Since hitting pause wasn’t an option, Chaz began to train more on his treadmill, finding the motivation he needed in an app called Charge Running. His longtime girlfriend, Kyra, introduced him to the platform, which allows people all over the world to run together virtually. Even lengthy sessions fly by, he says, and the close-knit, supportive community pushes him to keep his goals front and center.

An Olympic flag flutters in celebration of the 2016 Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. | Photo by Lazyllama / Shutterstock

At age twenty-six, Chaz has more on his plate than just running. He earned a master’s degree in social work at the University of Denver last year and now works for the Massachusetts Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired. He had always believed he would go into law enforcement and even completed a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice. But LHON changed his career plans. Not because he couldn’t go into law enforcement; rather, it inspired him to help people in the same way he’d been helped. “When I lost my sight, my case manager gave me perspective about life not being over because I was blind,” he says. “Of course, I had friends and family as an outlet, but my social worker, Jacob, was a really influential person in the beginning.”

It’s been seven years since life changed forever for Chaz. There’s ongoing research into LHON, but he accepts that it’s almost certainly a permanent condition. And that’s okay. Always a glass-half-full kind of guy, he admits it was tough to find the positives in the beginning. Today, it’s easy for him to name the ways in which his life has changed for the better, and, as he’s fought to live life on his terms, he’s found enviable clarity about what’s important to him. “Working with people with disabilities is one of my passions; running is the other one,” he says. “And I want to keep doing both for as long as possible.”

— V —

Follow along with Chaz’s journey on Instagram @blackkidrunning. Learn more or download the Charge Running app at ChargeRunning.com.

Tori Phelps has been a journalist and writer for twenty-five years. A longtime VIE collaborator, Tori is committed to storytelling that honors the subject matter and inspires the reader. She lives, reads, and bakes vegan biscuits with her family in Charleston, South Carolina.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE