vie-magazine-seaside-florida-hero-min

An aerial view of the Seaside School expansion and two-story colonnade (digital rendering over an aerial photograph by Fletcher Isacks) | Rendering courtesy of Thadani Architects + Urbanists

Born to Love Urbanism

By Dhiru A. Thadani

I was born to love urbanism.

I spent the first seventeen years of my life in south Bombay, within the colonial city. I continue to have a love affair with its magnificent assemblage of civic, academic, and cultural institutions, public parks, mid-rise apartment buildings, and tree-lined streets. I was, of course, unaware that my life was not typical. Within the burgeoning populous of the city, very few lived in agreeable urbanism. The rest of the city did not embody the same planning principles employed in my neighborhood.

Over time, I gradually became conscious of another form of civilization—village India. Both the urban and village forms of habitation were formed intensely by a sense of community. The large city I was born in had many communities living in and around it, intermingled with each other.

Regardless of size, both forms of community cohered through the same method of mobility—walking. When I came to America as a teenager, I was shocked to find myself deprived of an autonomous life because I did not own a car. At first, I was able to immerse myself in the community that college life offered, but I longed for the true city. Upon graduation and beginning professional practice, I continued to be a student of urbanism. This study became more focused when I began to teach.

My relationship with Seaside, Florida, began in the early 1980s when Andrés Duany came to the Catholic University of America to lecture. He discussed the idea of making a town, the constituent parts of which included an integrated mix of uses that commonly support daily life—housing, offices, retail, and civic institutions such as schools, churches, a post office, and a community meeting hall—all arranged in a memorable block structure with walkable streets where pedestrians were given priority over cars. He argued that since the 1950s these building uses had been exported to suburban locations, and the current sub-urban land use and zoning laws forbade meaningful assemblage and thus prohibited the true making of place.

In the Seaside plan, the actual areas of each constituent part were based on empirical research conducted by Duany and his partner, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, along with pioneering developer Robert Davis and his partner, Daryl Davis. These four progenitors had driven around the southern United States discovering and exploring small towns that were beautifully conceived and that provided their residents with a sustainable quality of life. Their study tour yielded source material that would be emulated and incorporated into Seaside.

- Digital renderings of the new boardwalk between the Coleman Pavilion obelisk and Bud & Alleys, which is currently under construction with carpentry by Jim Foley | Rendering courtesy of Thadani Architects + Urbanists

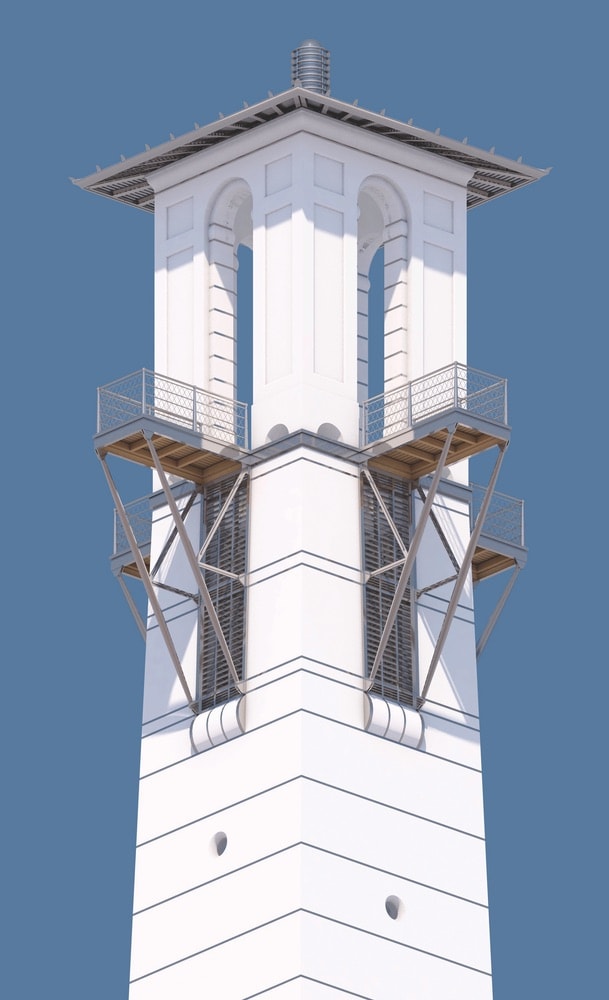

- A detailed rendering of the Seaside Tower by Léon Krier | Rendering courtesy of Léon Krier

- Street artist Gaia painted this mural commemorating architect and professor Vincent Scully on the iconic purple wall at 25 Central Square in January of 2018. | Photo by Jordan Staggs

Dismayed by the suburban landscape proliferating across America, fellow professor Peter Hetzel and I had started to incorporate urban contextual exercises in the beginners’ undergraduate design studios that we directed. We both had come of age in large cities, so the suburbs were somewhat foreign to us; although we had been there, we didn’t understand the attraction. After hearing Duany’s lecture, we became intrigued with the idea of using this yet-to-be-built town of Seaside as the framework for teaching physical and cultural context, climate constraints, and building morphology. Working with the Seaside master plan and the then-embryonic form-based code, we embarked on a five-week design studio project. Although our students focused on the buildings they were designing, the Seaside plan and code were teaching them urbanism. A by-product of this exercise was a scale model of the entire town, with every building represented.

For thirty years, I watched like a surrogate uncle as Seaside grew. Before 2011, my visits had been fleeting. In January of that year, I was selected to be an Escape to Create artist in residence in the town. During that stay, I was heartened by the amicable nature of the place, the welcome I received, and how easily I adapted to becoming a citizen. In contrast, my time living in Washington, D.C., had more to do with visual beauty, choices afforded, and access to cultural institutions. Life there could be described as urban anonymity rather than engaged citizenry.

My bond with Seaside further solidified when I was honored with the Seaside Prize in 2011. Awarded annually by the Seaside Institute, the prize recognizes individuals who have made significant contributions to the quality and character of their communities and are considered thought leaders of contemporary urban development and education. Many of the prize recipients have been my mentors; they have inspired me to research, analyze, and share knowledge as they benevolently shared their philosophies and experiences with me. That group includes the dramatic, passionate, and erudite architectural historian Vincent Scully, who taught at Yale University for over fifty years and at the University of Miami for over twenty years. Scully’s death in November of 2017 inspired Robert Davis and me to commission a mural honoring him in Seaside. It was painted on an unadorned purple wall that faced Scenic Highway 30-A at 25 Central Square. Scully was an early supporter of the New Urbanism movement, he loved Seaside, and he supported the many planning and architectural talents who were responsible for challenging the status quo and making a livable environment based on traditional planning principles.

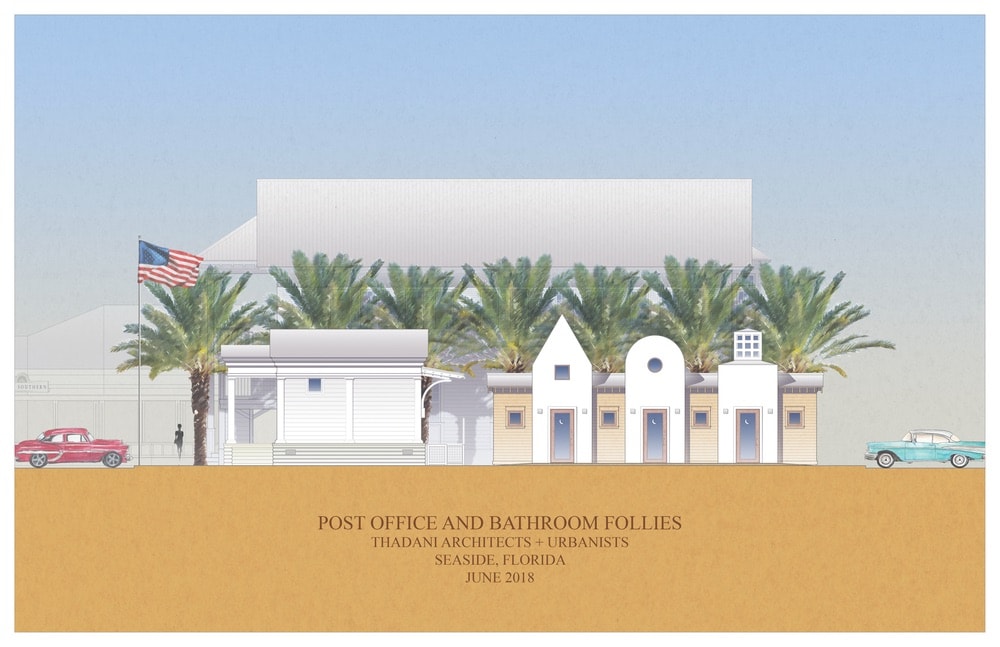

Elevation rendering of the new bathrooms and relocated Post Office building that will be between Sundog Books and The Art of Simple | Rendering courtesy of Thadani Architects + Urbanists

The idea for my book Visions of Seaside was conceived during my artist residency there. I became aware of the numerous projects that had been designed for sites within the town but were never built. I knew of Léon Krier’s prolific drawings for Seaside, but my research unveiled a magnitude of design drawings of extremely high quality. Many architects, urbanists, and builders have been drawn toward Seaside, hoping to build there and share in its success. Indeed, countless design schemes were submitted for the twentieth-anniversary competition held in 2001. Captivated by this discovery, I discussed the idea of a book, at that time to be titled Unbuilt Seaside, with Robert and Andrés. They were more than encouraging, and after the first draft, we agreed to expand the scope to include essays, developmental drawings for the Seaside Plan, and imaginative interventions to complete the town.

Since the publication of Visions of Seaside, Robert and I have continued to explore interventions and to work on projects in Seaside. Master plans are living documents and should not be frozen in time. They should be reviewed every five to ten years as market forces, demographics, and regional context change. The economic success of Seaside and the 30-A corridor could not have been foreseen in the 1980s. It was unimaginable that Seaside would be the cultural center for the region. Today, the public realm of Seaside caters not only to its residents but also to twentyfold that number in daily visitors. Hence, the open spaces of Seaside need to continually be refurbished to accommodate day-to-day living.

Our work at Seaside has primarily focused on the public realm. Along the Gulf Coast, I have designed a new walkway to the beach for the Coleman Obelisk Pavilion, a new beach access walkover for Bud & Alley’s restaurant, and a new public boardwalk between the two. These projects intend to visually and physically connect residents and visitors to the Gulf and the beautiful, fine white sand that graces the beaches.

These projects intend to visually and physically connect residents and visitors to the Gulf and the beautiful, fine white sand that graces the beaches.

The Lyceum has been another focal point for development. In 2012, I was involved in the design of the Academic Village to provide affordable housing for students and scholars. Recent projects include plans for the expansion of the Seaside School to cater to kindergarten through eighth-grade classes. We have completed a two-story arcade that frames the Lyceum lawn, as well as an outdoor amphitheater at the north end. Under construction is Quincy Plaza, a pedestrian table that interrupts Quincy Circle between the Gateway building archway and the Lyceum lawn. The intent is to enhance the pedestrian experience and strengthen the axial relationship between Central Square and the Lyceum.

To realize the long-term goal of building the Seaside Tower designed by Léon Krier, the Seaside Post Office must relocate. The decision to close Seaside Avenue’s connection to the Central Square created a viable site for the post office, which has become one of the town’s most iconic landmarks. Its new location also offered the possibility of building much-needed public bathrooms and bicycle parking in a plaza filled with palm trees.

- Seaside founder and visionary Robert Davis | Photo by Brendan Babineaux

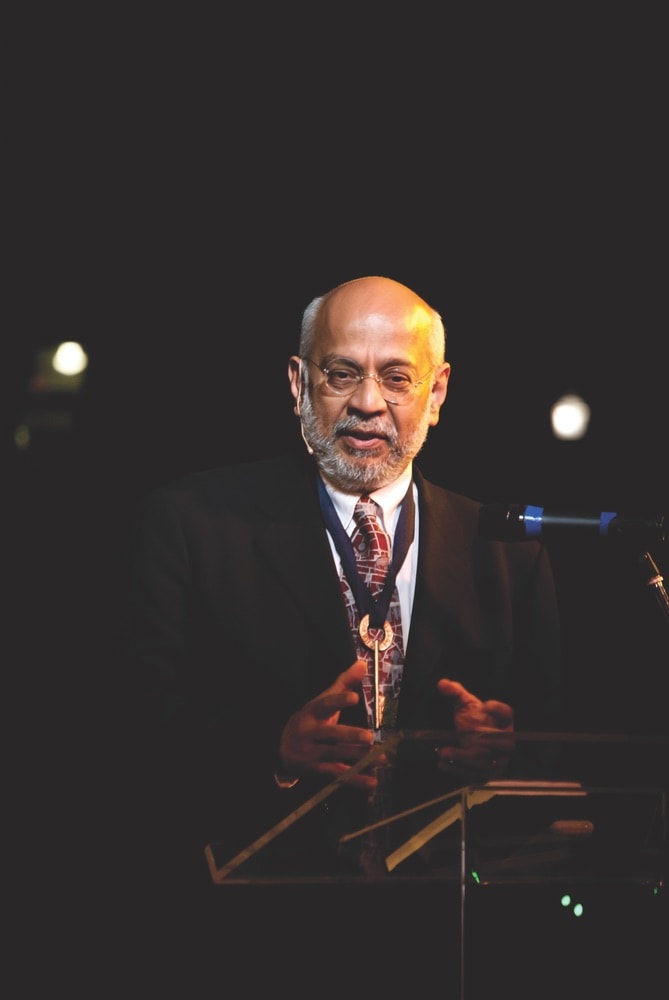

- Architect, visionary, and author Dhiru A. Thadani | Photo by Brendan Babineaux

I believe that the success of Seaside is based on love: Robert’s love for the land and the memories it holds; Daryl’s love for Robert and her willingness to move to a desolate part of Florida and aid him in realizing his dream; Andrés and Lizz’s love for humanity and their search for making a model sustainable community. It shows in the homeowners and the millions of visitors who fell in love with the town the moment they set foot there and in the residents of Walton County who love the place and identify Seaside as home. In a recent luncheon conversation with the world-renowned Danish planner Jan Gehl, we concluded that great places could only be created if clients and designers truly loved people. That sentiment is the essence of Seaside’s success, making beautiful places for all people to enjoy, where they can love and feel loved.

Like any love story, Seaside is not perfect. It is, in fact, messy, funky, and full of missteps, lost opportunities, unintended consequences, and heartbreaks. Still, it attracts an excess of a million visitors each year. Additionally, over a million people have stayed in the town through the rental program and many return each year. Residents and visitors have experienced an environment where all age groups are welcome, where daily needs are within walking distance, and where you can live car-free. The town continues to introduce millions of suburbanites to the joys of urban living, furthering the love of urbanism, architecture, and art and the importance of a public realm.

- This aerial view of the beach access at the Coleman Pavilion obelisk illustrates the wedge shape of the stairs as they descend to the white sand, creating an illusion the sides of the ramp are parallel. Michelangelo used this technique at Capitoline Hill in Rome. | Photo by Fletcher Isacks

- Stacia and Annamieke descending on the new Bud & Alley’s beach walkover | Photo by Jack Gardner

The development of Seaside over the past thirty-five years is closely allied with the three steps of smart change identified by the Russian thinker Peter Palchinsky. First, Robert and Daryl, with Andrés and Lizz’s help, created a new way to develop coastal property, challenging the status quo. Secondly, they tried their idea on a small scale and with minimal debt, so that any failure would be survivable. Finally, being part of all decisions, they intuited a feedback mechanism to inform them of failures, successes, and the reasons for each. They munificently shared their findings with others so the development model could be promulgated.

In this day of high-speed action, intense population growth, threatening climate change, and monotonous mass production, a place such as Seaside stands as evidence that good things take time, that small is beautiful, that democratic freedom can exist within a set of rules, and that beauty and love are essential to uplifting the human spirit.

— V —

Dhiru A. Thadani, AIA, is an architect and urbanist who has been in practice since 1980 and has worked internationally. He has been the principal designer of new towns and cities and urban regeneration, neighborhood revitalization, and infill densification projects. Thadani is the author of The Language of Towns and Cities: A Visual Dictionary and Visions of Seaside: Foundations/Evolution/Imagination/Built and Unbuilt Architecture and the coeditor of The Architecture of Community by Léon Krier.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE