vie-magazine-alaqua-hero-min

Hood with a recent rescue of adorable six-week-old puppies at the Alaqua Animal Refuge

Big Dreams Require Big Vision

Saving Animals One Day at a Time

By Wayne Pacelle | Photography by Romona Robbins

Laurie Hood has never been an armchair advocate for animals. She’s more of an arm twister.

Growing up in the central Louisiana town of Alexandria—at the midpoint of a diagonal line between New Orleans and Shreveport in the northwest—Laurie’s first foray into advocacy came in the second grade.

“Boys were shooting songbirds with BB guns,” Hood tells me. “I was upset about these poor birds and I wanted to do something about it.” Channeling the centuries-old moral adage that the boy throws stones at the frog in fun, but the creature dies in earnest, the indignant seven-year-old told her mother—whom Laurie credits with instilling “a sense of empathy in me early on”—that someone had to do something.

Armed with her petitions demanding that the boys stop their mischief, Hood went house to house urging the adults in her neighborhood to rein in the kids. Even in Louisiana, where the license plates are emblazoned with the motto “Sportsman’s Paradise” and hunting and fishing are common field sports, shooting songbirds has long been out-of-bounds.

Hood goes barefoot chic on the refuge in a cotton dress from local boutique Kiki Risa, a supporting business.

“Pretty much everybody signed,” Hood recalls, with the residents motivated perhaps as much by their affinity for animals as their admiration for the indomitable little blonde with her twist on petitioning city hall. In the end, the town fathers and mothers told the boys to shoot at inanimate targets only and to leave the white-breasted nuthatches, Carolina wrens, and any other songbirds alone.

Animals always had a central place in Hood’s life; she and her mom took in strays, making their home something of a makeshift refuge. But like most animal lovers, she wasn’t part of an organized movement, especially because her area had few groups with a presence or profile.

She moved to Northwest Florida during her senior year of high school, but then bounced back and forth between the two states, attending Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge for her undergraduate degree. After a few marketing jobs, she settled in the Florida Panhandle town of Destin to build a family with her husband, Taylor (they have two sons, Crockett and Garner). It would take some years before helping animals on a significant scale became all-consuming, and with no major group to join and lead, Hood realized she’d have to build it herself.

Laurie and Taylor Hood with their two sons, Crockett and Garner, along with their dogs, Kylie and Moonpie, and cat, Red.

Alaqua Animal Refuge Is Born

Typically, animal welfare groups are born of crisis. Some horrible event or festering condition is so jarring and awful that it inspires leaders to act and work to turn the situation around. That’s the creation story of Alaqua Animal Refuge.

Hood’s epiphany came in 2007 when she and a friend found their way to a rural shelter in Washington County, Florida. Fans of adoption, they went to the only operating shelter they could find, a private facility that contracted with neighboring Walton County and other county animal control agencies to hold stray and surrendered dogs and cats. It was a converted chicken coop, absent any comforts or flourishes, chaotic with the sounds of relentless barking, the air filled with the unpleasant odors of ammonia and other animal waste, and scared animals crowded into rudimentary cages.

- Hood bottle-feeding piglet Nugget, a newcomer to Alaqua and the runt of the litter

- Amanda together with her piglets in an Alaqua Animal Refuge barn

- JR and Little Feather spend time together in the pasture.

To Hood’s astonishment, one dog had an arrow protruding from his head. Other dogs had fallen ill and went untreated. There were no volunteers and only a handful of poorly paid personnel. The facility did not advertise that it was open to the public, and by the looks of it, according to Hood, the operators didn’t seem like they were planning on having visitors at all. The facility held the animals for a few days, consistent with state law, and then euthanized them, typically with a heart stick (a lethal intracardiac injection that is widely considered inhumane). Only a handful of animals who went in made it out alive, with the kill rate exceeding 95 percent.

And this was the best—essentially the only—“humane” organization in the entire region, “except for a small group of dedicated women who did spay-and-neuter work,” Hood says.

Hood and her friend asked about the adoption fee for a mother dog and her eight puppies. It would be $900 for the entire family, perhaps without any medical services such as sterilization or vaccination. The fee, however, would be waived if she came on behalf of an animal welfare charity.

Hood told them she’d be back the next day and asked them not to kill any of the animals in the interim. That night she went online, created the Alaqua Animal Refuge, and presented the paperwork to the shelter staff the next day. She left the facility with not only the nine dogs but also thirty other animals. She and Taylor lived on ten acres, but they had no animal sheltering capacity. “We put the animals in the barn, and I made cages,” she says. According to Hood, Taylor was as agreeable as anyone could be to having their home turned into an animal shelter. It would be the start of his journey. (At the time, he was the general manager of a highly successful automobile dealership that has been a high-profile family business for decades, and last year, he gave that up after twenty-five years to become director of operations at Alaqua, where he oversees animal care.)

Hood frolics with her favorite white cockatoo, Ivory.

Born overnight, Alaqua not only grew in the months and years ahead but also stirred the conscience of people throughout Northwest Florida. Today, a small staff and four hundred volunteers take care of packs, herds, and orphans, and thousands visit the refuge every year. Since its inception, Alaqua has adopted out more than fifteen thousand animals, but even that number vastly understates the impact and says nothing about its range of education and advocacy programs.

While the work has been tangible and constitutes a remarkable upgrade in animal welfare for the region, Hood reminds me that she and her team are still overwhelmed. The sprawling, beautiful, well-tended grounds, which I first visited in 2016, are always at capacity. Even with the drumbeat of outreach and education that Alaqua conducts for the community about spay-and-neuter and responsible pet care, “We get as many as a hundred surrender requests a day,” Hood says. She is frustrated that Alaqua is only able to take three or four animals a day. That means that in a county of fifty thousand, and a region of perhaps two hundred thousand people, she’s getting requests to surrender three thousand animals a month, or thirty-six thousand a year—a figure perhaps larger than the combined intake totals for the three or four biggest shelters in New York, a city of eight million people.

The Future of Animal Welfare

These days, she’s focused on developing one of the boldest undertakings in animal welfare anywhere, and Northwest Florida is the backdrop and the beneficiary. According to Walton County Sheriff Michael Adkinson, a key partner with Hood on animal issues, she possesses the best qualities in leadership, engaging pet lovers and conservationists, philanthropists and architects, politicians and prosecutors, and just about anybody else whose forearm she can gently twist. “Laurie has that rare combination of passion and vision,” said the lawman, who is also president of the Florida Sheriffs Association. “Few people possess both qualities. She’s an outlier in the best sense of the word.”

Thanks to a land donation from the late businessman and conservationist M.C. Davis and his wife, Stella, plus cash gifts of $500,000 from the Dugas Family Foundation (the family that started Dollar General) and $1 million from Raven and Ryan Jumonville, Hood’s got a one-hundred-acre stage to build on in Freeport, Florida, adjacent to the E.O. Wilson Biophilia Center. She calculates that the first phase of the “small town” she’s building will cost $15 million—about fifteen times her current annual budget. The scale of work she’s imagining is breathtaking.

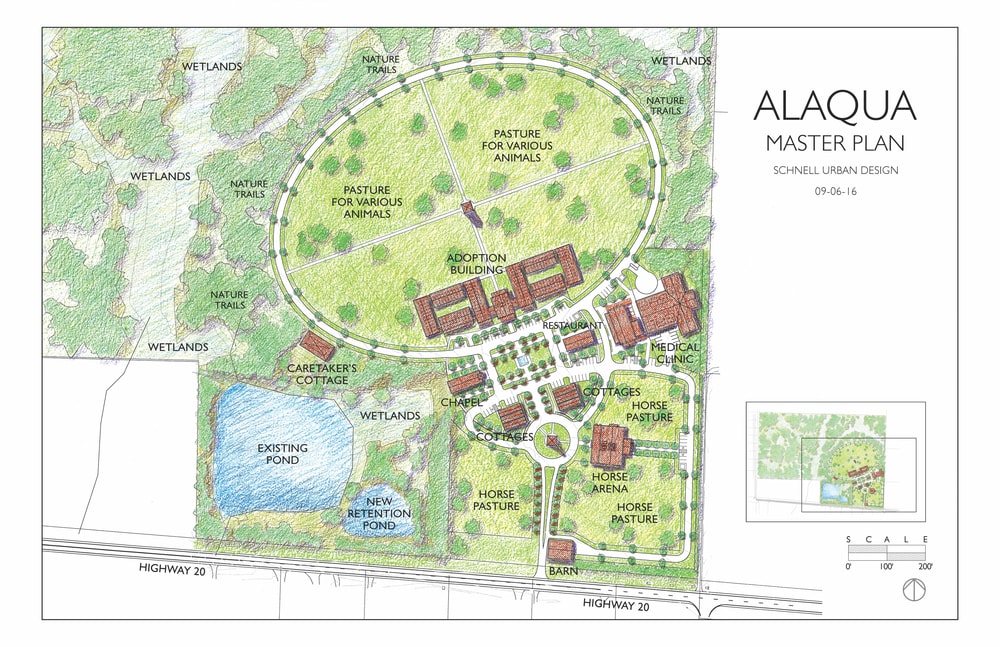

The master plan of the future Alaqua Animal Refuge complex

Rendering courtesy of Schnell Urban Design

The proposed complex includes dog and cat shelters, pastures for large domesticated mammals, a fenced forty-acre habitat for wildlife deemed unreleasable, a covered horse-riding arena, a veterinary hospital, and a forensics lab to aid in anticruelty investigations. She’s also building a bird sanctuary (to deal with the unfinished business of her childhood activism). The new facility will also have an education center—even a chapel and a healing center for people experiencing grief after losing a pet. At the complex, veterans and kids with autism will have the opportunity to interact with animals and heal. She also imagines it as a place where people will celebrate weddings and other meaningful life experiences in the presence of animals, getting a firsthand view of what the human heart can achieve when it’s open to the needs and suffering of other creatures.

And she’s doing this in the mostly rural South, where animal problems are acute and the investments in animal welfare through the decades have been sparing at best. In her area, there’s barely any capacity to solve animal homelessness, to aid wildlife injuries and rehabilitation, or to tackle cruelty investigations. The good news is that the people of Northwest Florida seem more than ready to join Hood’s crusade. So far, I haven’t run into anyone who doesn’t think she’ll make it happen.

Indeed, even if she must go door-to-door in the towns of Northwest Florida to succeed, she’s more than capable of putting a petition in hand and hitting the street.

Changing the Law for Good

Hood is also doing animal cruelty investigations in an area where arrests for animal abuses were unheard of. That work is so robust that Nat Geo Wild, the cable network, had more than enough material to complete a series on Hood and Walton County animal control officers called Animal PD. The show first aired in April 2018, and episodes are available for streaming on Fox’s website.

Nothing was more painful to Hood than her first cruelty case in 2010, involving a miniature horse named Champ. Walton County officials delivered what was left of Champ to Alaqua; he was a miniature horse who should have weighed three hundred pounds but came in at a ghost-like fifty pounds. “I still don’t understand how he survived,” Hood reminds me. “I slept in the barn with him for ten days,” providing companionship, food, and water, and just trying to show him that all humans aren’t evil.

Local prosecutors brought charges against Champ’s former owner, but two successive judges balked at conducting a formal proceeding despite overwhelming evidence that the horse had been starved. The decision not to proceed by the judges meant that Champ could be taken from Alaqua and go back to the owner. That was too much for Hood, and she went public with the details of the case. News of the aborted legal proceeding went viral, and people from all over the world wrote to authorities and expressed their outrage. Florida State Attorney William “Bill” Eddins came in on high and invoked a little-used procedure to trump the decision of the judges. In the end, the state won a conviction, albeit without jail time. Alaqua never relinquished custody of Champ, and he’s lived there in peace and security for eight years now, seeing the best of humanity every day.

Hood in action on an episode of Nat Geo Wild’s Animal PD

Photo courtesy of National Geographic

Hood hasn’t been content to see prosecutions alone; she’s also determined to fortify the law so that future prosecutions will have more force. When she and Walton County officials rescued 117 animals in a neglect case, the anticruelty statute allowed prosecutors to bring only a single charge against the defendant. Hood found the law deficient and went to Tallahassee to bring this to the attention of Matt Gaetz, a Republican state representative and devoted animal welfare advocate. With an assist in the other chamber from Gaetz’s father, Don, who was then the state Senate President, the group worked to upgrade the law to allow prosecutors to bring multiple counts of cruelty where warranted.

In the years since, Hood has made a habit of working with the Gaetz clan (Vicky Gaetz, the matriarch of the family, is also deeply devoted to animal welfare). Hood and the Gaetz family worked together to pass legislation to ban bestiality after Hood and Walton County law enforcement came across a dog who was the victim of sexual violence and for which they had little legal recourse. “Laurie is the animal welfare guru of Northwest Florida,” Matt Gaetz tells me. “There is little she cannot do for the creatures who share our planet. From fund-raising to caring for infant life to helping me change laws to punish abusers, Laurie is ‘all in’ for animals.” The outspoken and quick-witted Gaetz is now a US representative and continues his partnership with Hood in Congress, where he’s backing legislation to create a federal anticruelty statute and a federal ban on bestiality. One bestiality website, where people interested in having sex with animals gather online, has more than a million registered users.

- Hood in action on an episode of Nat Geo Wild’s Animal PD Photo courtesy of National Geographic

- Laurie Hood and Breezy Adkinson

- Hood with veterinarian Dr. Amy Williams and a few of the staff and volunteers that make up the invaluable team at Alaqua Animal Refuge

While Hood helps animals in crisis, she recognizes that she can’t rescue her way out of the problems animals endure and must also work to change public policy. That’s why she’s also worked so closely with Kate MacFall, state director of the Humane Society of the United States, and others to stop the trophy hunting of black bears in Florida, and she’s now engaged in an effort to ban greyhound racing. Don Gaetz, now retired from the Senate, recently served on the state’s Constitution Revision Commission; the bipartisan group referred a racing ban to the statewide ballot for a vote this November. Florida is the hub of the withering but still stubbornly defiant industry—twelve of the eighteen remaining tracks in the United States are in Florida—so voters could finish off a good portion of the industry by enacting the constitutional amendment this fall. A Florida greyhound dies on the track every three days, and Hood plans to campaign across the Panhandle to put a stop to needless risks to dogs for a sport that attracts few spectators these days. It’s an animal industry, she says, that has outlived its usefulness in a world where other forms of entertainment command much more interest from citizens drawn to games of chance.

“Laurie has a servant’s heart,” Sheriff Adkinson says. “She has raised the capacity of this region to do good,” and he’s proud to be a key player in a public-private partnership to end euthanasia of healthy animals in Northwest Florida and to demand that people adhere to the rule of law.

Thanks in large part to Hood and her refuge, attitudes toward animals and conditions for them are changing for the better in Northwest Florida. The region is experiencing a demographic and economic high tide. There are thousands of wealthy seasonal residents who’ve purchased luxurious Gulf-front homes and a far larger stream of visitors trekking there to enjoy the views, the beaches, and the year-round warmth. Together they are buoying the job market and the success of the region.

Hood says Alaqua already attracts a bevy of tourists, and that the new complex will rival the museums, zoos, shopping plazas, and other essential stops for visitors who will then return to their communities and tell the story of the extraordinary complex for animals in the Florida Panhandle. Among the wave of visitors will be animal advocates with their own aspirations to do good, some perhaps wondering how they might replicate what’s been created at Alaqua. Hood assures me she’s ready to share her vision with all takers.

— V —

Visit Alaqua.org to learn more and find out how you can help today.

Wayne Pacelle, formerly the president and CEO of the Humane Society of the United States, is the author of two New York Times bestsellers, The Bond and The Humane Economy.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE