vie-magazine-art-deco-tulsa-architecture-hero-min

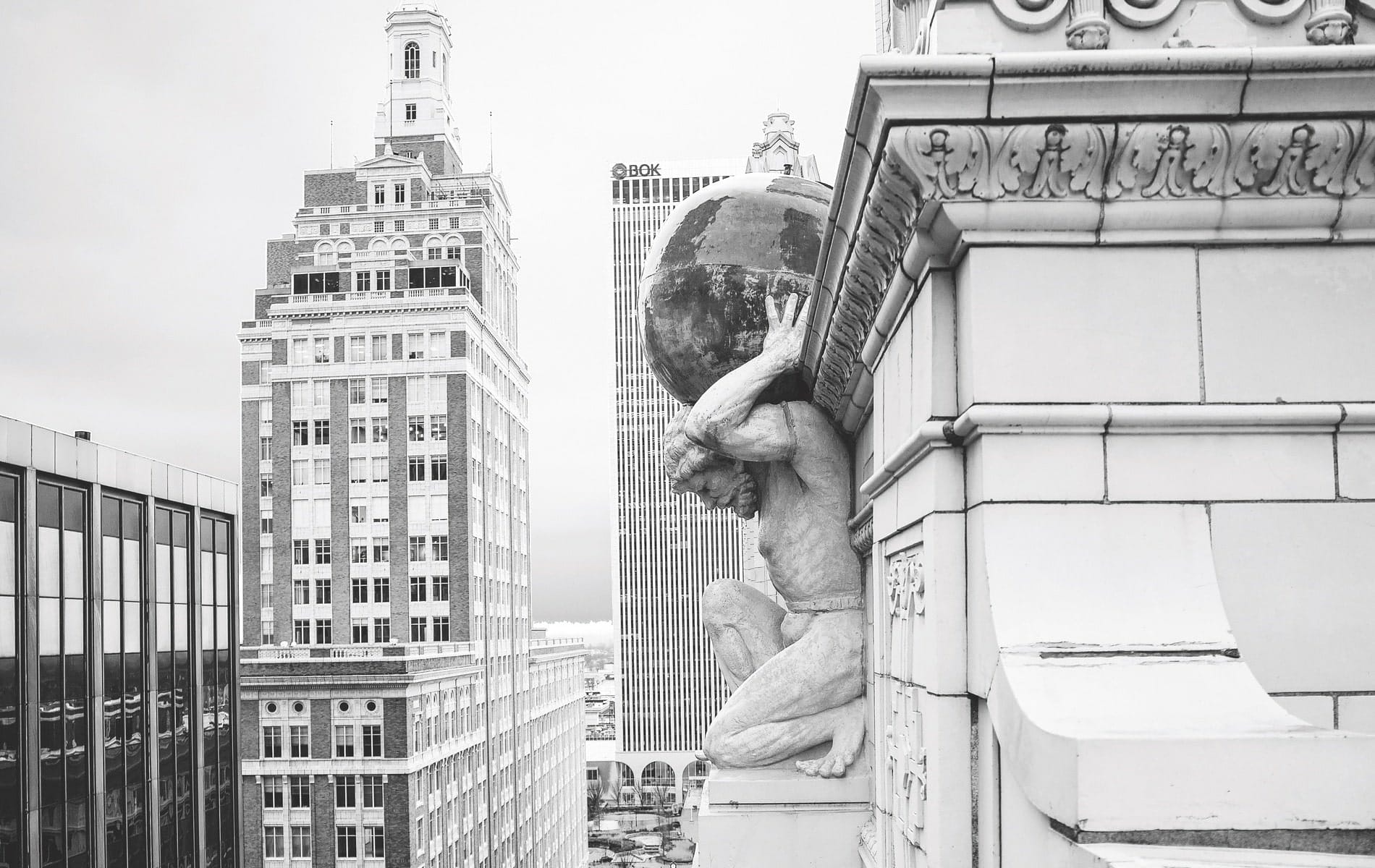

The Greek Titan Atlas is depicted holding up the earth on the top of Tulsa’s Atlas Life Building, built on Boston Avenue in 1922.

From Oil to Art Deco

Tulsa’s Architectural Legacy

Story and photography by Steve Larese

Atlas strained under the weight of a turquoise and gold globe as I leaned over the edge of the twelve-story building bearing his name, the Atlas Life Building. A kaleidoscope of tiny umbrellas dotted Boston Avenue below, and reflections from red and green traffic lights streaked across its rain-wet pavement like melting crayons. The street scene could have been in any number of big cities, but on this particular drizzly afternoon, I was exploring the surprising forest of architecture in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

From my perch, I saw the French neoclassical 320 South Boston Building (finished in 1929) across the street, which rises twenty-two stories with its temple-like cupola. The massive BOK Tower (completed in 1976) at the end of South Boston Avenue is a fifty-two-story, half-scale replica of the World Trade Center by architect Minoru Yamasaki, who designed the original. To my right, a trapezoid of green copper-top crowns the thirty-six-story Gothic-style Mid-Continent Tower (begun in 1918), and to my left, a pyramid of green and sienna tiles tops the twenty-four-story Gothic Revival/art deco Philtower Building (1928).

The Atlas Life Building is capped by the terra-cotta Titan chosen to convey strength and support. The eponymous insurance company opened it in 1922. There is a Greek myth in which Atlas refuses Perseus shelter because he fears Perseus will steal his golden apples. In retribution, Perseus turns Atlas into stone. This struck me as ironic because, since 2010, the building bearing his name has been a very hospitable Courtyard by Marriott hotel in the heart of Tulsa’s downtown Deco District.

Many people are surprised to learn that this prairie city of 413,000 people has some of the most diverse architecture in the nation. Turn-of-the-last-century art deco and midcentury modern masterpieces mingle with new award-winning structures such as the swirling BOK Center (2008), which draws upon Native American and art deco design elements. Frank Lloyd Wright designed a house here, named Westhope, for his cousin who was the publisher of the Tulsa Tribune (Wright’s only skyscraper, Price Tower, is in nearby Bartlesville). The aforementioned BOK Tower has taken on even more significance since the loss of the World Trade Center. Tulsa’s skyline on the Arkansas River is a vibrant showcase of architectural design and has been for the past one hundred years. But why?

“Oil,” Ted Reeds enthusiastically tells me on a tour of Tulsa’s downtown gems. Reeds is an accomplished architect who helped found the Tulsa Foundation for Architecture in 1995 as a response to Tulsa’s older buildings being forgotten, neglected, or razed. “We had wealth bubbling up, and we had input at the same time from people who really looked at a city as something to support and to make for everyone. We were incredibly fortunate.”

- Intricate ceiling details inside the Philtower Building, which was completed in 1928

- A tunnel below the street connects Tulsa’s Philtower and Philcade Buildings. The tunnel was built for security purposes by oil baron Waite Phillips at the height of his career.

The 1905 discovery of the immense Glenn Pool oil field outside of Tulsa would earn Tulsa the sobriquet the Oil Capital of the World. Wildcatters flowed into Tulsa. One of those hoping to strike it rich was twenty-three-year-old Waite Phillips. He left coal mining in Iowa for the oil fields of Oklahoma to join his brothers, Frank and L. E., who had named their new company Phillips Petroleum. Waite would branch off and become a multimillionaire overnight with his oil production and supply company. With his wealth, he built many of Tulsa’s most iconic buildings, spending millions on growing Tulsa’s stature to compete with New York and Chicago. He would later gift many of his properties to the Boy Scouts of America and the city of Tulsa, stating, “The only things we keep permanently are those we give away.”

The Tulsa Foundation of Architecture leads tours of historic properties throughout downtown, and I followed Reeds into the zigzag art deco Philcade Building where he excitedly pointed out Egyptian-style columns and other deco stylings. Lavish gold-leaf geometric designs on the arched ceilings of the lobby drip with crystal chandeliers that spread their warm light across terra-cotta trim decorated with flora and fauna. The lobby’s Sainte Genevieve marble (selected by Phillips as his wife’s name was Genevieve) was imported from Missouri.

“What makes Tulsa stand out architecturally is the quality of its diversity,” Reeds says. “Whether it’s art deco or midcentury modern or Sullivanesque classic, each one of these buildings stands tall here. Because of that, we have a legacy that we need to live up to. Ugly architecture is just not acceptable in Tulsa.”

Many people are surprised to learn that this prairie city of 413,000 people has some of the most diverse architecture in the nation.

When oil prices slumped in the 1980s, many of the city’s classic buildings were all but abandoned. In some cases, it was only the prohibitive cost of demolition that saved them. The 1925 Sullivanesque Mayo Hotel, which welcomed guests such as Charlie Chaplin and John F. Kennedy, narrowly escaped that fate and has reopened again as a luxury hotel. The Tulsa Club, an art deco masterpiece that was nearly rotting away, has been refurbished to the glory of its 1920s heyday and reopened to guests in May 2019.

“We forgot our legacy in the 1980s and ’90s, but that happened throughout the country,” Reeds says. “No one cared about the ‘old stuff.’ Fortunately, we’re making up for that.”

The next hour was a whirlwind of walking through busy buildings that were once empty and run-down. The 1917 Exchange National Bank, nicknamed the Oil Bank and today officially the Bank of Oklahoma, impresses with its ornate Beaux-Arts design. The Boston Avenue United Methodist Church, completed in 1929 with its soaring details, is considered to be one of the best examples of art deco architecture in the United States. Reeds’s stories of the men and women like the Phillipses who built Tulsa’s skyline, knowing that it would long outlast them, filled my head. I jotted down the names of Bruce Goff, Leon Senter, Edward Delk, George Winkler, and other renowned architects for further study.

Original zigzag art deco details on an elevator inside 624 South Boston Avenue—the Oklahoma Natural Gas Company Building, built in 1928—which now houses an event venue

“Buildings are nothing without people,” Reeds says to me at the end of the tour. “They can be the most beautiful buildings in the world, but they’re soulless without people.”

Office workers went about their workday as I craned my neck to take in the stone-relief-rosette ceiling of the Gothic Revival Philtower. Phillips had these huge rosettes carved in Italy and reassembled in Tulsa by the craftsmen who made them. We took the stairs to the basement level, where Reeds unlocked a vault-like door and flipped a switch to reveal an arched green tunnel. It felt like I was in a forgotten bunker. “I like to save this for last,” he says.The Philtower and the Philcade are connected by a semisecret eighty-foot tunnel that travels below Fifth Street. Phillips brought in miners to dig that tunnel.

The Philtower and the Philcade are connected by a semisecret eighty-foot tunnel that travels below Fifth Street. Phillips brought in miners to dig that tunnel. In 1927, he had a seventy-two-room Italian Renaissance mansion, Villa Philbrook, built on twenty-three acres south of downtown. It was the scene of quiet family strolls through the acres of manicured gardens and glamorous parties complete with a glass dance floor underlit with color-changing lights. Threats of kidnapping often marred the idyllic lifestyles of wealthy businessmen in this era. After the Lindbergh baby was kidnapped in 1932 and other high-profile threats, Phillips decided to move his family to the more secure, 4,255-square-foot fourteenth-floor penthouse of his Philcade. He surprised the city of Tulsa by donating Philbrook and its grounds to be used as a public art museum in 1939 before moving to California in 1942, where he died in 1964. He also donated the family ranch in New Mexico, Philmont, to the Boy Scouts of America. We walked through the tunnel underneath Boston Avenue and came out in the Philcade, tracing the route Phillips probably took hundreds of times.

The Philtower and the Philcade are connected by a semisecret eighty-foot tunnel that travels below Fifth Street. Phillips brought in miners to dig that tunnel.

There’s enough significant architecture in Tulsa’s downtown to warrant a full day of exploring, but there’s much more to see in the city’s other districts. Businesswoman Teresa Knox has purchased the Church Studio, built in 1915 as an Episcopal church and acquired in 1972 by Leon Russell as a recording studio. Russell’s friends, including George Harrison, Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, JJ Cale, Willie Nelson, Eric Clapton, and Bonnie Raitt, all passed through its doors. Tom Petty signed his first recording contract here with his band Mudcrutch in 1974. Knox has been painstakingly remodeling the studio back to its 1970s roots, including sourcing analog recording equipment from that era. The National Register of Historic Places added the Church Studio in 2017, and Knox plans to open it to the public in March 2020.

“We’ll have a gallery, an event space, and a theater in the basement for music-related films and intimate performances for the general public, as well as the recording space for artists,” she says. “First and foremost, I’m a Leon Russell fan, and second, I love historic preservation. I’m just really proud of Tulsa and want to share our history.”

Knox has also refurbished Harwelden Mansion, the 1923 English Tudor/collegiate Gothic home of oilman Earl Harwell. She returned the fifteen-thousand-square-foot mansion on three acres to its 1920s elegant styling and opened it as an event space and boutique hotel in May 2019.

- The marble interior of the Gothic Revival–style Mid-Continent Tower in Tulsa is just as stunning as when the building first opened in 1918.

- Modern decor and top-notch amenities meld seamlessly with the Tulsa Club’s historic architectural details. | Photo courtesy of Tulsa Club

The oil that built Tulsa’s architectural masterpieces in the 1920s and ’30s also fueled the cars that made Route 66 an American icon. Tulsa has one of the best-preserved stretches of the Mother Road left in the nation, and Eleventh Street again glows with neon and a renewed sense of spirit. It’s seen the opening of the eclectic Mother Road Market with such merchants as Decopolis, which sells Tulsa-related art deco items, and Buck Atom’s Cosmic Curios on 66. Its towering space cowboy statue installed in May 2019 is already a must-stop photo op for Route 66 lovers.

And Tulsa’s new philanthropists, such as George Kaiser and the George Kaiser Family Foundation, have made it possible for the city to build new public spaces, including Guthrie Green and Gathering Place. These free spaces are filled with live music, playgrounds, trails, and open space. Through its Tulsa Remote program, the foundation recently offered $10,000 to work-from-home tech-industry professionals who would relocate to Tulsa for at least a year, thereby diversifying Tulsa’s economy further. The response was overwhelming; applications flooded in from all over the country and the world.

Local museums, such as the Woody Guthrie Center that examines the life and times of the Oklahoma writer of “This Land Is Your Land,” are so impressive that Bob Dylan has chosen Tulsa as the recipient of his archives. OKPOP, a museum dedicated to Oklahoma’s contributions to popular culture—from Will Rogers and Route 66 to Saturday Night Live’s Bill Hader and musicians such as the Flaming Lips and Vince Gill—is scheduled to open in 2020. It lies across from the historic Cain’s Ballroom, where everyone from Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys to the Sex Pistols played.

Stunning art deco details abound in the lobby of the Tulsa Club, a 1925 building that was empty for many years. The former social club was renovated and reopened as a hotel in May 2019. | Photo courtesy of Tulsa Club

Taking Reeds’s parting advice after our tour, I headed out to find the once-threatened art deco Tulsa Fire Alarm Building. It’s adorned with a terra-cotta frieze that includes dragons turning into fire hoses and firemen heroically holding axes. Designed by Frederick Kershner and built in 1931, its Mayan temple–inspired theme is just another almost-forgotten architectural gem awaiting rediscovery in Tulsa.

— V —

For more information about Tulsa’s architecture, visit the Tulsa Foundation for Architecture at TulsaArchitecture.org and the Tulsa Preservation Commission at TulsaPreservationCommission.org.

VIE contributor Steve Larese explored many of these historic buildings when they were empty and in disrepair. He’s thrilled to see them restored to their former architectural glory.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE