VIE_Magazine_MAY22_article_Suzanne_Pollak_HERO-min

El Jaleo (1882) by John Singer Sargent | Courtesy of Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

A Woman in Her Own Right

By Suzanne Pollak | Photography courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

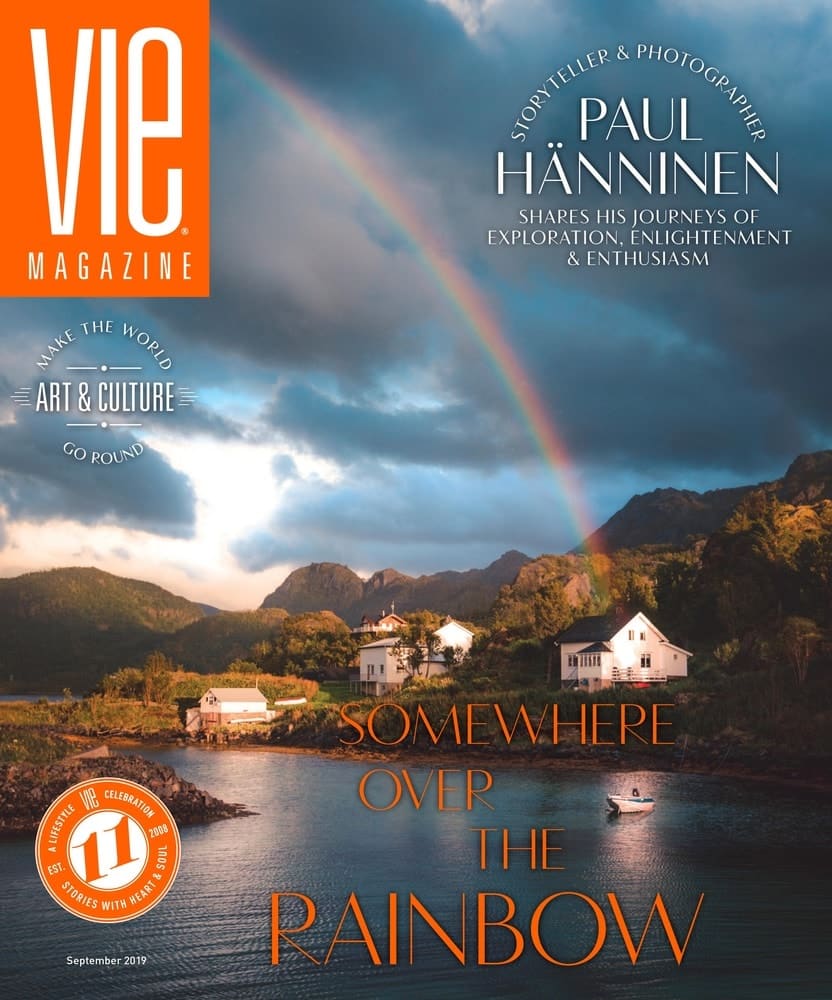

What could be better for the soul on a stormy day than to be inside the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum? Nothing could have prepared me for the out-of-this-world experience in that moody, misty palace on a morning when snow was falling so heavily that even the toughest Bostonians worried (the museum itself opened an hour late). Inside, it was unexpectedly lush with subtropical flowering plants, nasturtium vines hanging twenty feet from fifteenth-century balconies, light streaming in from the skylight four stories above, and snow sliding sideways against the window panes.

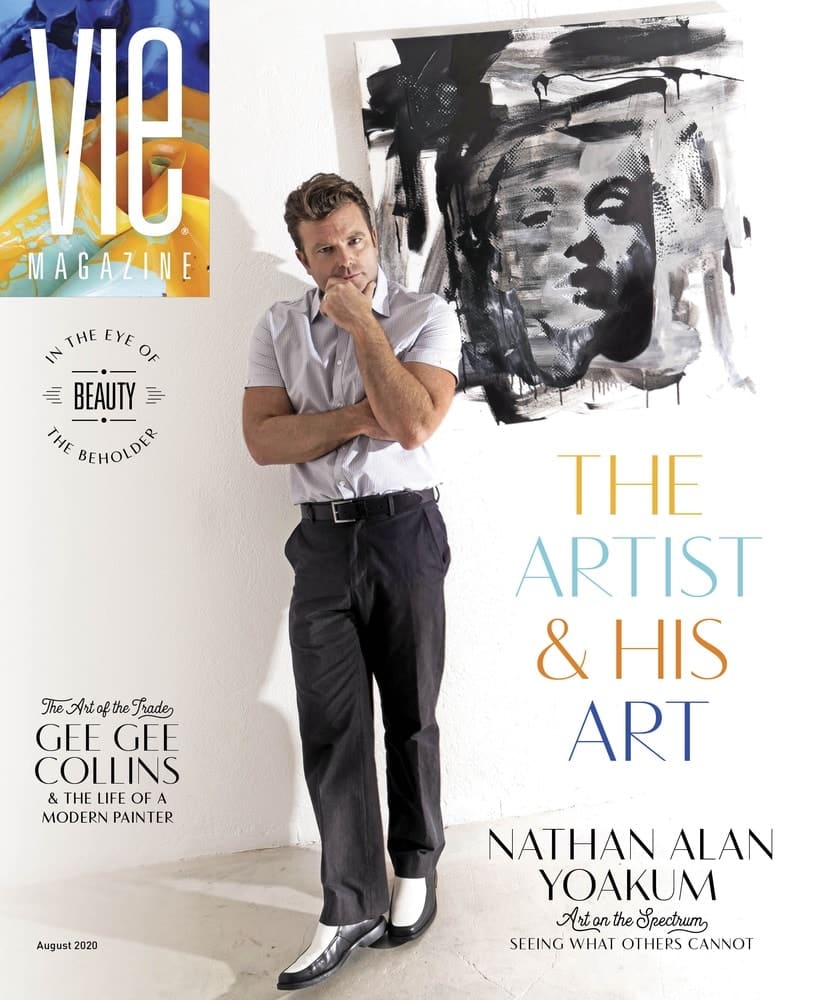

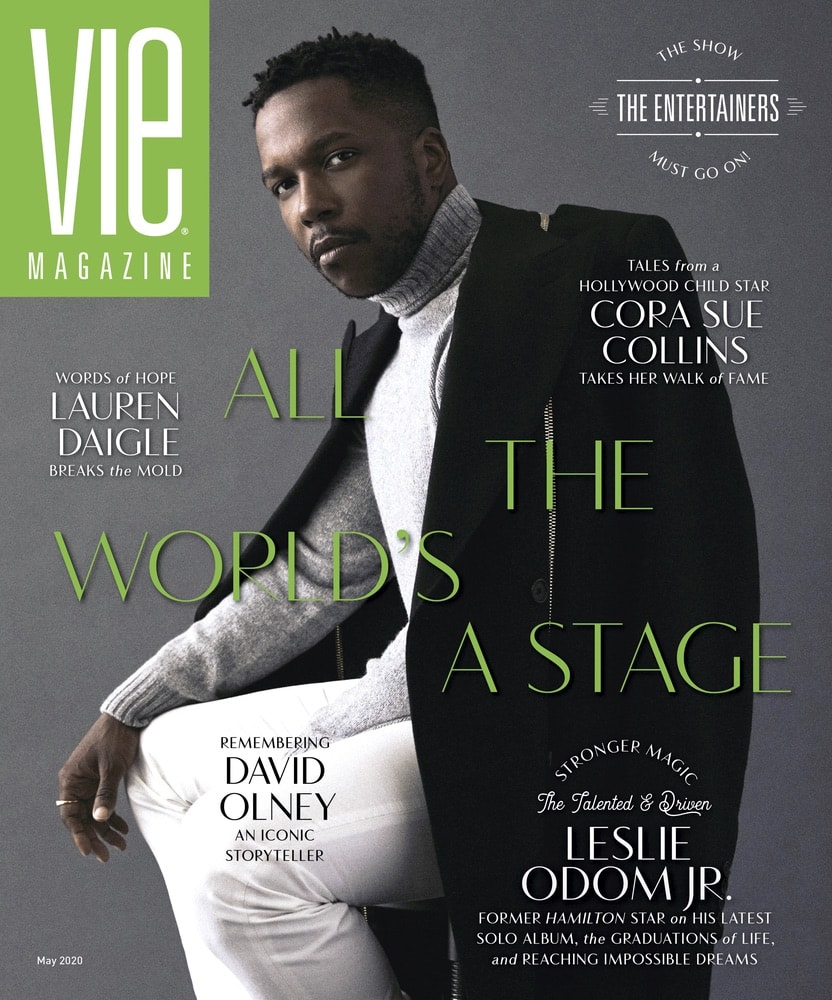

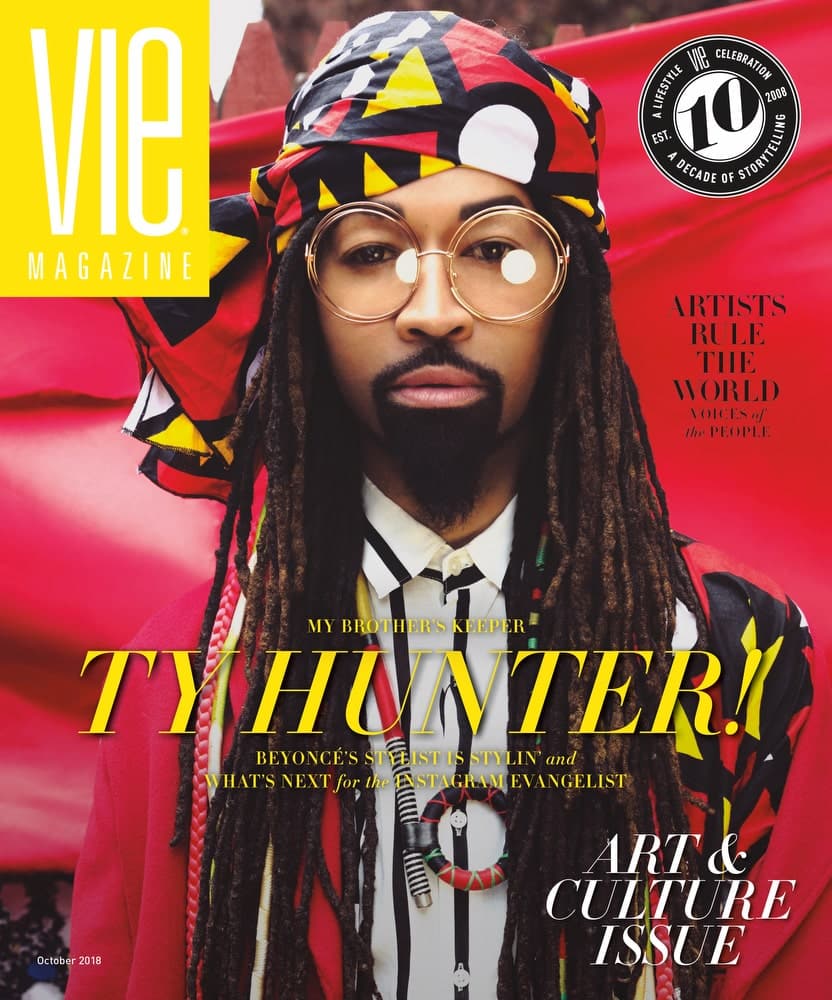

Isabella Stewart Gardner—“Bella” to her friends and family—put together a collection of art and furnishings so varied in a house so unique, it could bear the tagline “The Coolest Museum in the World.” She lived her life as an artist—not behind an easel in a studio but through experiences—lying in the Egyptian sand to understand the mysteries of the Sphinx, riding elephants and buffalo carts through the jungle to Angkor Wat, and being fascinated by Himalayan women who married multiple men. She had her Paris-made carriages gallop through Boston, arranged boxing matches for her lady friends to watch, and decorated herself with diamonds, pearls, and décolletage, back and front. She craved attention and lived exactly as she pleased. Bella would be considered fierce even today—a piece of work and an art project all in one.

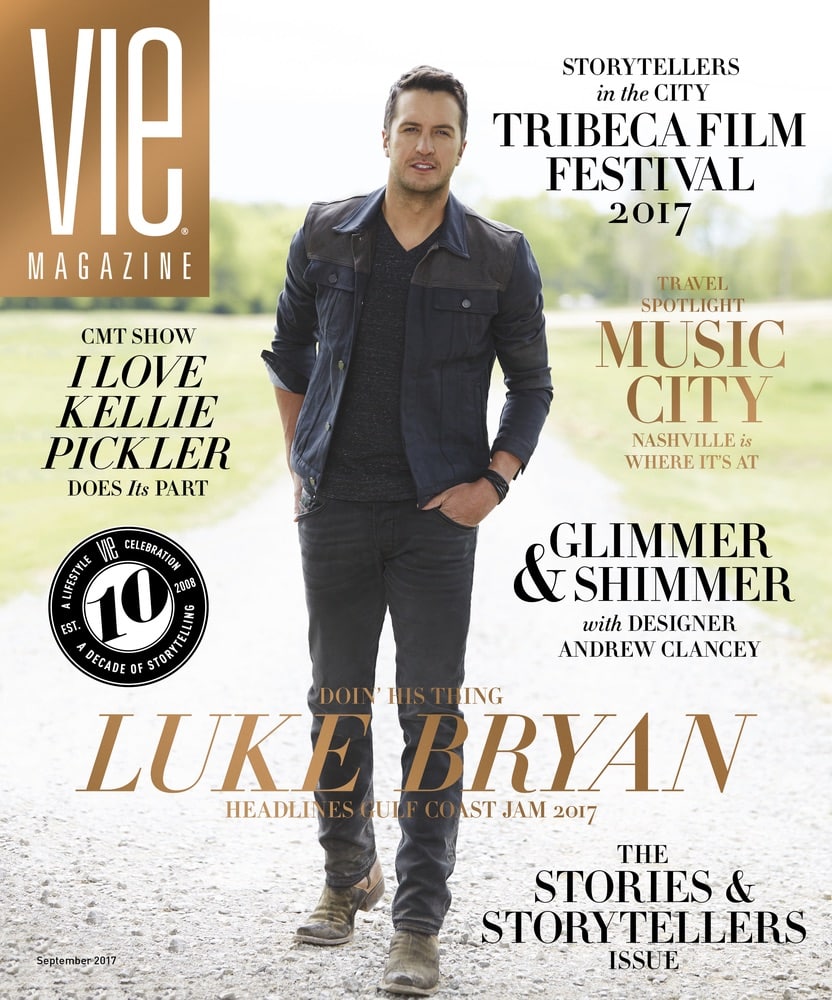

A portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner by her friend John Singer Sargent

Her passions became her mission. She brought a new world to Boston, whose citizens she viewed as opinionated and haughty when they did not accept her. In turn, she enjoyed annoying, irritating, and outraging Puritan Bostonians. But to this place and its people, she also brought an imaginable gift—the beauty of another world and time in a magical setting, a living, breathing museum at her former residence.

Everything here is a work of art, inside and out: from the architecture, lighting, and atmosphere to Bella’s collection of paintings, prints, drawings, furniture, sculptures, tapestries, church vestments, ceramic and glass objects, rare books, musical scores, autographs, African arrows, Japanese lanterns, a Tibetan prayer wheel, and walking sticks. All are priceless works of art, and how they relate to each other is another one.

A house museum differs from other museums. House museums are intimate spaces and offer a special way of viewing their creators’ obsessions. Most pieces are unlabeled in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and low lighting makes the large, showy rooms still feel like a home. The art objects feel like they have always been there. Even works by the old masters feel like a natural part of the place instead of standalone pieces to admire.

to this place and its people, she also brought an imaginable gift—the beauty of another world and time in a magical setting, a living, breathing museum

An Anders Zorn portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice

The fourth floor was Bella’s house, though she used the whole place as her fiefdom known as Fenway Court. She loved sitting on the marble bench in the courtyard surveying her sculptures and blooming scented plants, watching the light change throughout the day and seasons. She kept the Gothic Room private, for friends only. A controversial portrait of Bella by John Singer Sargent, one of her well-known houseguests, hung there. He came to live in Fenway Park in the spring of 1903, writing later that his “thoughts have taken permanent abode at Fenway Court.”

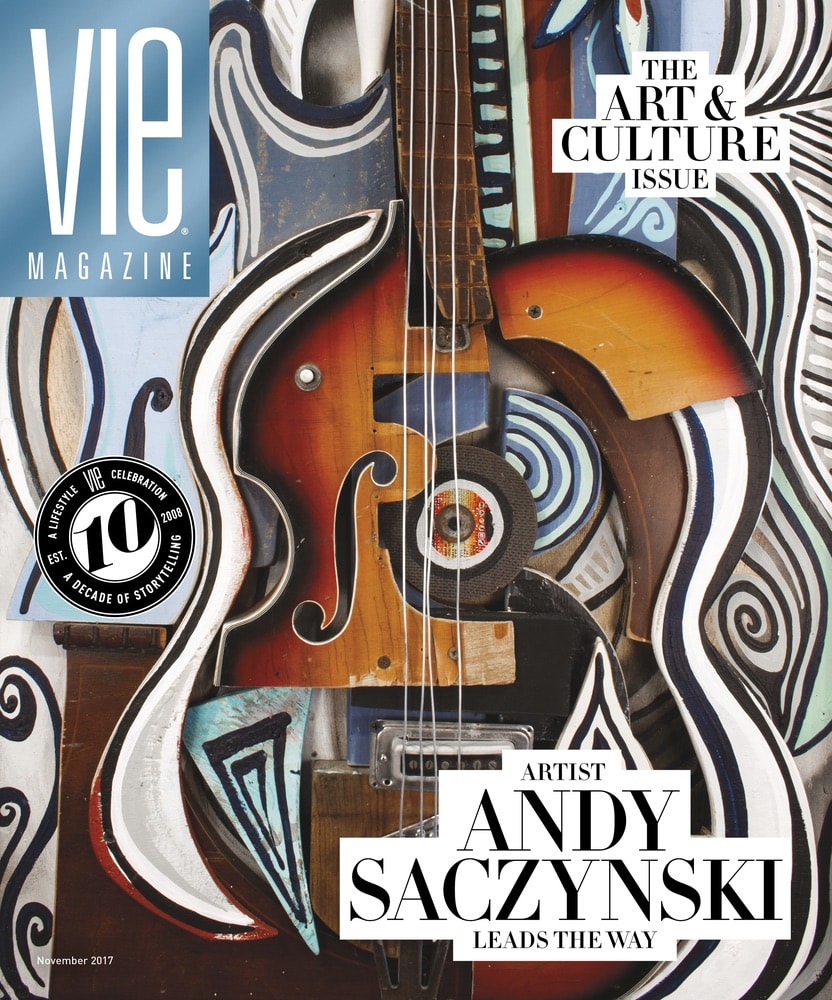

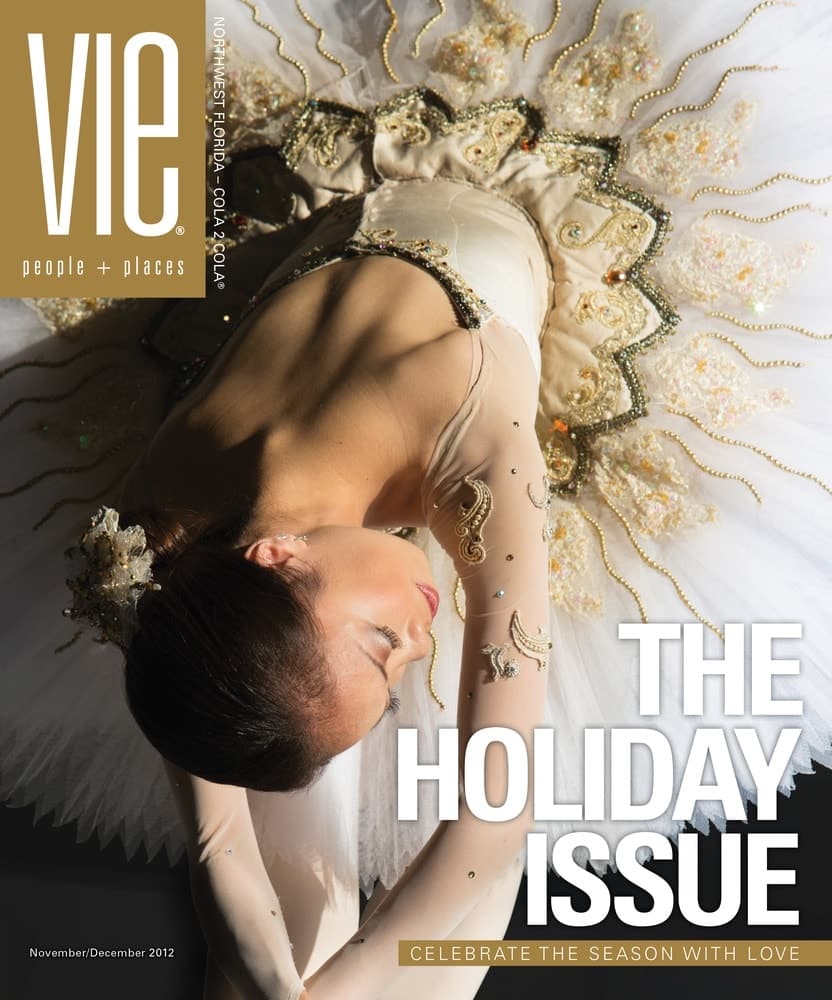

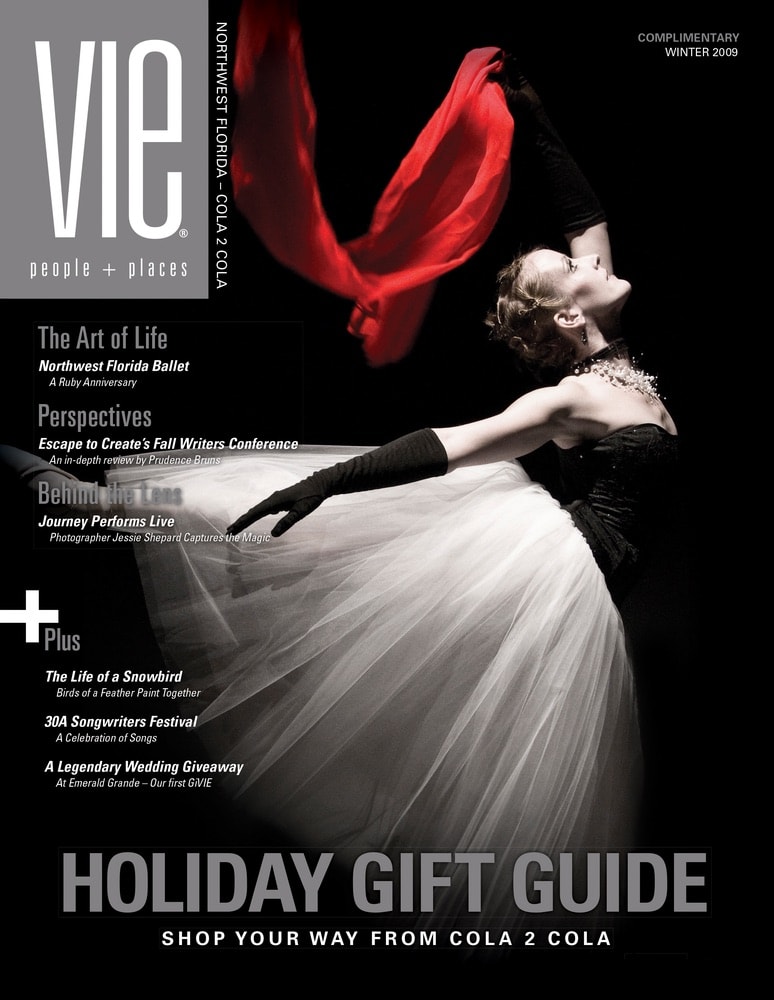

Bella gave dinners in the Spanish cloister. At one of them, she invited her cousin Thomas Jefferson Coolidge with one purpose. She wanted him to see his enormous Sargent painting El Jaleo hung above the fireplace set in a Moorish arch frame and lit from below. On loan to her for decades, she tried to buy the painting from him, but he refused. So, she sat him across from the painting, and he agreed he could not take it away, so spectacular was Sargent’s masterpiece in that setting.

Concerts and performances were organized under her direction. Trumpets blared from windows high above the courtyard. Other times, Gregorian chants rang from balconies on high, enchanting listeners below. In 1903, Bella threw the house museum’s opening gala on New Year’s night. Guests who once ostracized her were silenced with admiration—and maybe envy. The courtyard was lit by candles and in full bloom. The Boston Symphony played Mozart, Bach, and Schubert. William James wrote to Bella that her party was “quite in line of a gospel miracle.”

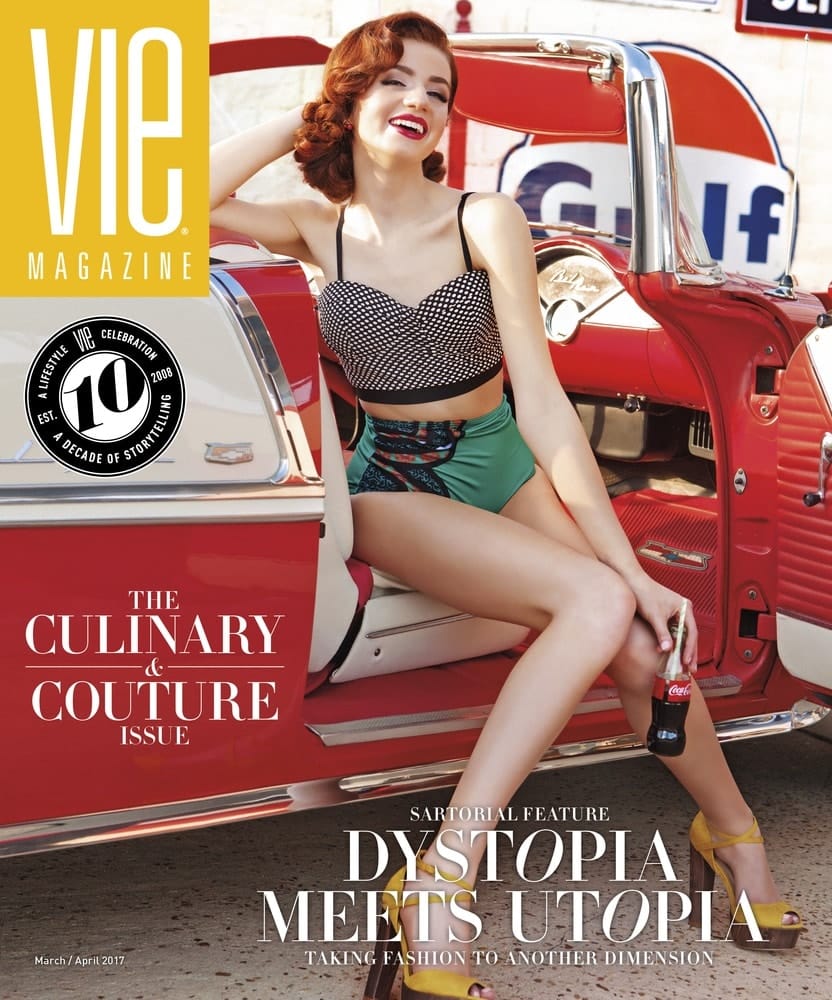

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston

Bella received her large inheritance from her father in 1891. When her husband died in 1898, she also received two trusts worth two million dollars each. She used the money to build herself, her city, and, ultimately, the world a fifteenth-century Venetian palace in the middle of a cold New England city. She would fill it with a king’s ransom worth of treasure—a palace created by a woman, all for herself. Many among us have surely wished to live in such a place, but would we have the confidence and courage to build one? Could we win battles with the architect, feud with building inspectors, know which dealers to work with in the cutthroat art world, or outbid and outfox J. P. Morgan and other art collecting robber barons? Would we be so picky and bossy that more than 120 years later, each object still sits or hangs where we placed it?

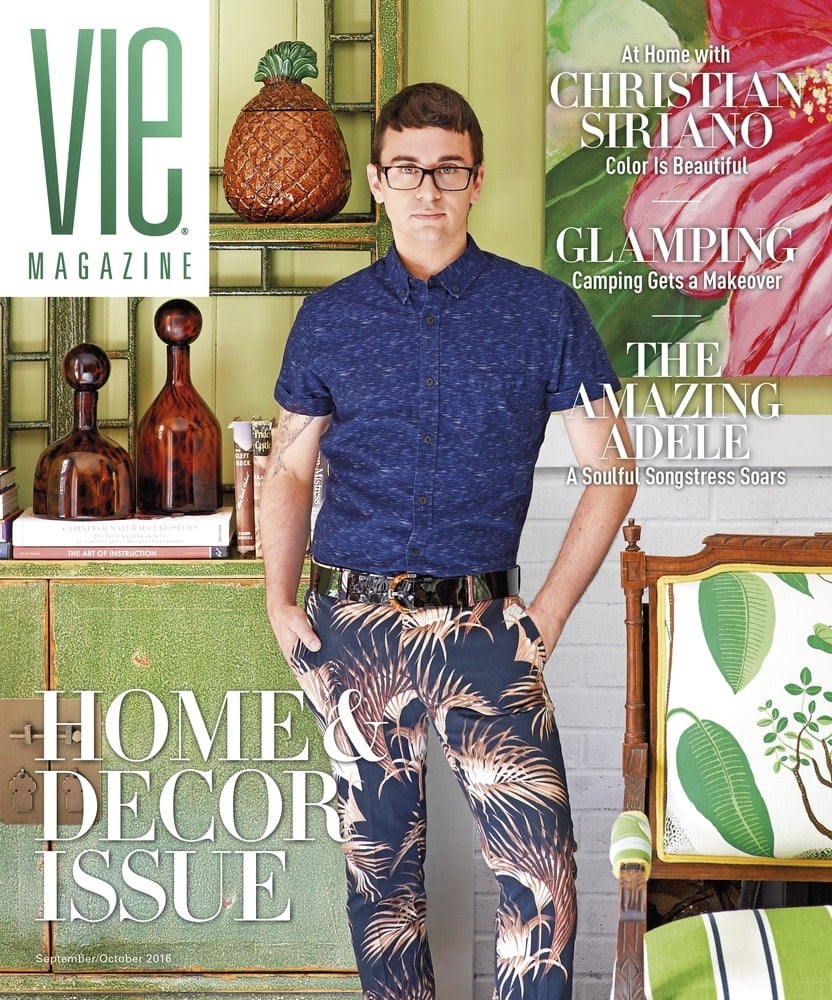

Isabella Gardner is considered one of the greatest art collectors and museum builders in America

This woman was a trailblazer. Bella made her first blockbuster purchase (without the aid of an art advisor) in 1892 when she bought Johannes Vermeer’s The Concert (c. 1664) at auction. She was the first American to own a Botticelli and the first to bring a Matisse to an American collection. There were no limits to her learning or collecting. Whatever moved her, she bought: Titian, Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Raphael, Botticelli, Manet, Degas, Whistler, and Sargent, of course. She trusted her gut. Her collecting partner, Bernard Berenson, once sold her a Rembrandt that she was not crazy about but, on his urging, bought anyway. A hundred years later, her instincts proved impeccable—it was discovered to be a fake.

Even today, this sui generis woman would be a renegade. Anyone who knows what moves them and dives in, learns more, and makes it their lifelong passion and pursuit can move mountains. Isabella Stewart Gardner is considered one of America’s greatest art collectors and museum builders. Her gift opens up a new world and invites us to see things in a different way.

— V —

Learn more or plan a visit to the museum at GardnerMuseum.org.

Suzanne Pollak, a mentor and lecturer in the fields of home, hearth, and hospitality, is the founder and dean of the Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits. She is the coauthor of Entertaining for Dummies, The Pat Conroy Cookbook, and The Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits: A Handbook of Etiquette with Recipes. Born into a diplomatic family, Pollak was raised in Africa, where her parents hosted multiple parties every week. Her South Carolina homes have been featured in the Wall Street Journal Mansion section and Town & Country magazine. Visit CharlestonAcademy.com or contact her at Suzanne@CharlestonAcademy.com to learn more.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE