vie-magazine-wilderness-destinations-botswana-hero-min

Roaming with the Big Cats

Adventure in Botswana’s Wild Frontier

By Xenia Taliotis | Photography courtesy of Wilderness

“Lioness at ten o’clock.” Vasco, projects manager for Wilderness, Botswana, was in the back of our jeep, seemingly with his eyes closed. I had binoculars over my glasses, eyes wide open, but even with all that, I saw nothing but swaying grass.

But then something flicked. I focused my binoculars and saw the swishing tail of my first free lion. Her lithe, golden form rose and moved languidly toward us. Soon she was by our vehicle, her bourbon eyes measuring us. Realizing we were neither food nor foe, she sauntered off, her unhurried movements belying the fifty-plus miles per hour she can run when hunting.

A little later, we saw her in full-throttled predator mode, staking out a cheetah devouring a kill and then pounding across the plain in an audacious snatch and grab to seize the carcass for her cubs.

The cheetah, the weakest cat, has only one defense—speed. Tense-tight, she watched the stalking lion, assessing the diminishing distance between them while tearing at the flesh voraciously, timing precisely when she would have to surrender her meal and sprint for her life. Grabbing one last chunk, she sprang just as the lioness made her move.

I was at Chitabe, one of three camps run by leading conservation operator Wilderness that I would visit during my stay in Botswana, in Southern Africa. I had chosen Botswana because it is one of the best safari destinations in the world, with a genuine commitment to wildlife preservation and some of the most stringent anti-poaching laws in Africa.

And I’d gone with Wilderness because it has been working in Botswana for more than forty years and has several camps there, each in a different location to give access to diverse ecosystems, with options to view animals from land, water, and the air, as well as at night. Its impressive eco-credentials include solar-powered camps, eco-friendly detergents and toiletries, reverse-osmosis water filtration, and an excellent record of supporting local communities. Finally, I’d heard great things about how knowledgeable its rangers were.

Chitabe covers 22,000 hectares of wilderness in the heart of the UNESCO-listed Okavango Delta—an alluvial fan of lagoons, channels, and islands that, at six thousand square miles, is the world’s largest inland wetland area. It draws the hunters—lions, cheetahs, leopards, crocodiles, hyenas, jackals, and wild dogs; the hunted—impalas, lechwe, giraffes, zebra, and baboons; and much else in between, including elephants, buffalo, hippos, vultures, fish eagles, kingfishers, and rollers.

I’d arrived from the UK the night before that first drive. I had gone straight to my tent—a luxurious thatch-capped villa decorated in the colors of the Kalahari and Okavango and floating on an expansive timber deck. I needed sleep, but as one sense—sight—shut down, another—hearing—ramped up. Hours before I saw any wildlife, I heard it. Throughout the night, animals sang, trumpeted, roared, scampered, chased, caught, fled, flew, created life, and ended it.

Soon after I finally fell asleep, I was woken by a guide bringing me tea and asking me to be ready in ten minutes to be escorted to reception. The walk wasn’t long, but it might have brought me closer to the wildlife than was advisable. “We share our camps with the animals,” said Vasco. “This is their land, and we must respect that. Elephants and baboons are often outside the rooms, so we accompany guests to and from their villas at night.”

Game drives started early, and it was cold. Despite multiple layers, I dove into the poncho and blankets provided, tucking a hot water bottle into them. We set off before the pink and gold of a rising sun began to color the sky, our senses sharpened by anticipation and the earthy aroma of wild sage.

As dawn melded into day, indistinct shapes took form. There were jackals standing on gargantuan termite mounds and giraffes gracefully picking their way through the grasslands, their long necks and legs a miracle of form and function. Studies by Dr. Julian Fennessy, co-founder of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, show the species is experiencing a silent extinction. In the 1700s, Africa had about a million giraffes. Now there are just 117,000.

Impalas and red lechwe were all around, zebras grazed up ahead, and ostriches and roadrunners raced comically past.

“This is their land, and we must respect that.”

For all I saw, Tank, our guide, saw—and showed us—more. Intuition, experience, and an affinity with nature seemed to have given him superhuman hearing and vision. He cut the engine and pointed to a leopard draped over a baobab tree branch. After eating, the creature seemed like he wouldn’t move for days, but Tank said he’d spring if an opportunity came his way. That appeared soon enough when an impala danced toward death. Twenty more steps, and it would be dead meat. Thankfully, it turned and bolted.

We drove on. Tank leaned out of the jeep and showed us the tracks of one of the most endangered creatures on earth—the painted or wild dog. We followed the tracks and found a pack of about fifteen. I was moved to tears by them, by their coats of burnished gold, fall red, black, white, and brown, enormous round ears, and complex social relationships. Fiercely loyal to their pack and led by an alpha female, they communicate by touch, actions, and vocalizations and make important decisions by voting—yes, you read that right; they vote—by sneezing.

A century ago, five hundred thousand painted dogs roamed across Africa. Now estimates put the total population at 6,600. Needing to build up their numbers, individual groups go on puppy raids, abducting the young of another.

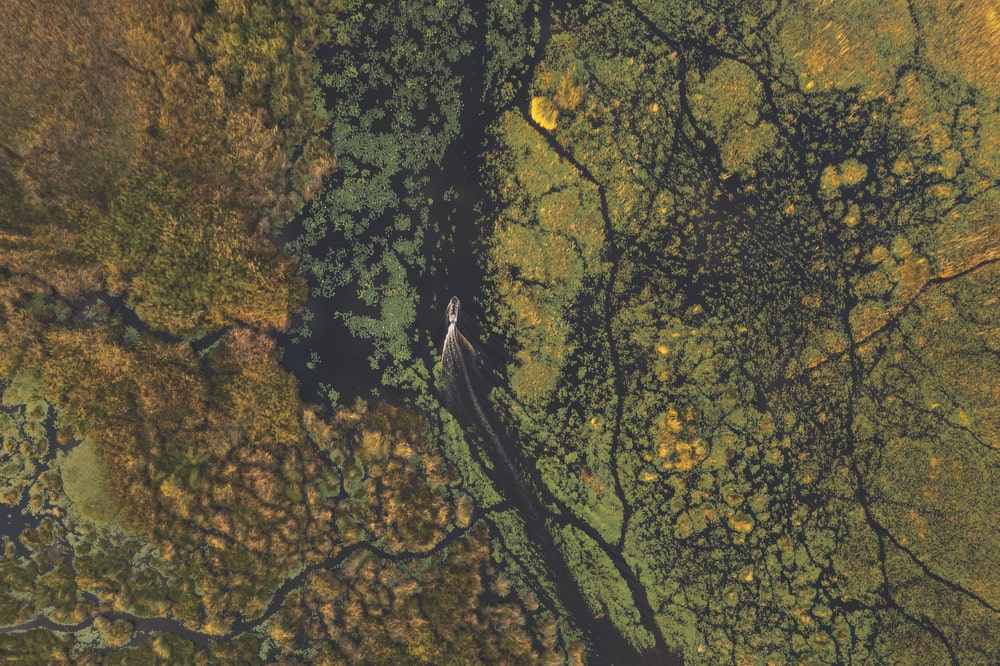

The next day, we left Chitabe for Vumbura Plains. Our flight took us across the water channels that feed the delta’s flood plains, mopane-forested islands, and marshlands. Seen from above, they appeared like arteries, keeping one of the world’s most important habitats alive.

When we arrived, my room—a beautifully designed indoor-outdoor space with wooden floors and an unobstructed view of the savanna—was unavailable, not because it hadn’t been prepared but because an elephant was having a snack by the door. I bided my time in the restaurant, enjoying a meal as rich in flavor as the landscape was in color, with plant-based options that satiated even meat lovers. As I ate, an elephant stopped so close to me that I could count every fold in his skin.

Later, we took a night drive to explore some of Vumbura’s 60,700-hectare wilderness. The two lion brothers who had taken over the territory from another pride walked silently past us, intent on finding prey. What a thrill it was to be utterly ignored by them.

The next morning, we drove through water channels to find elephants walking trunk to tail along the water’s edge. Occasionally, they would siphon gallons of water into their trunks to spray into their mouths or to give themselves a cooling shower.

We then swapped our vehicle for mokoro canoes to enjoy the beauty of the delta from the water. Emerald green reed frogs clung to blades of grass, malachite kingfishers flashed past in a flurry of sapphire blue and orange, and dragonflies darted all around.

A short flight took us to our final camp, DumaTau, a 111,300-hectare private concession in the Linyanti Wildlife Reserve overlooking the Osprey Lagoon, which had so much wildlife that I could have had a safari from my room. But I took a river cruise, which brought me within feet of a hippo raising its head out of the water, showing me a yawn that seemed to reveal eternity. We spent only a short time in her company before we followed the call of a troop of baboons. Their behavior was as familiar as our own. “Did you know they’re so terrified of snakes they faint at the sight of one?” asked our guide. No, but I do know several people who would do the same.

— V —

Visit WildernessDestinations.com to learn more or book your next safari adventure.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE