vie-magazine-national-braille-press-hero-min

The National Braille Press, headquartered in Boston, empowers the blind and visually impaired with programs, materials, and technology supporting braille literacy and learning through touch.

With a Human Touch

National Braille Press Keeps Braille Literacy Near at Hand

By Nicholas S. Racheotes | Photography courtesy of National Braille Press

Another September has come to the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston. There, in a historic building, situated within earshot of Symphony Hall and Northeastern University, a special group of people has gathered. Bankers, lawyers, educators, public relations specialists, retired corporate leaders, and other experts in their fields have all volunteered around a single purpose. They are committed to keeping persons with no or limited vision informed, enriched, and entertained through braille and other tactile products.

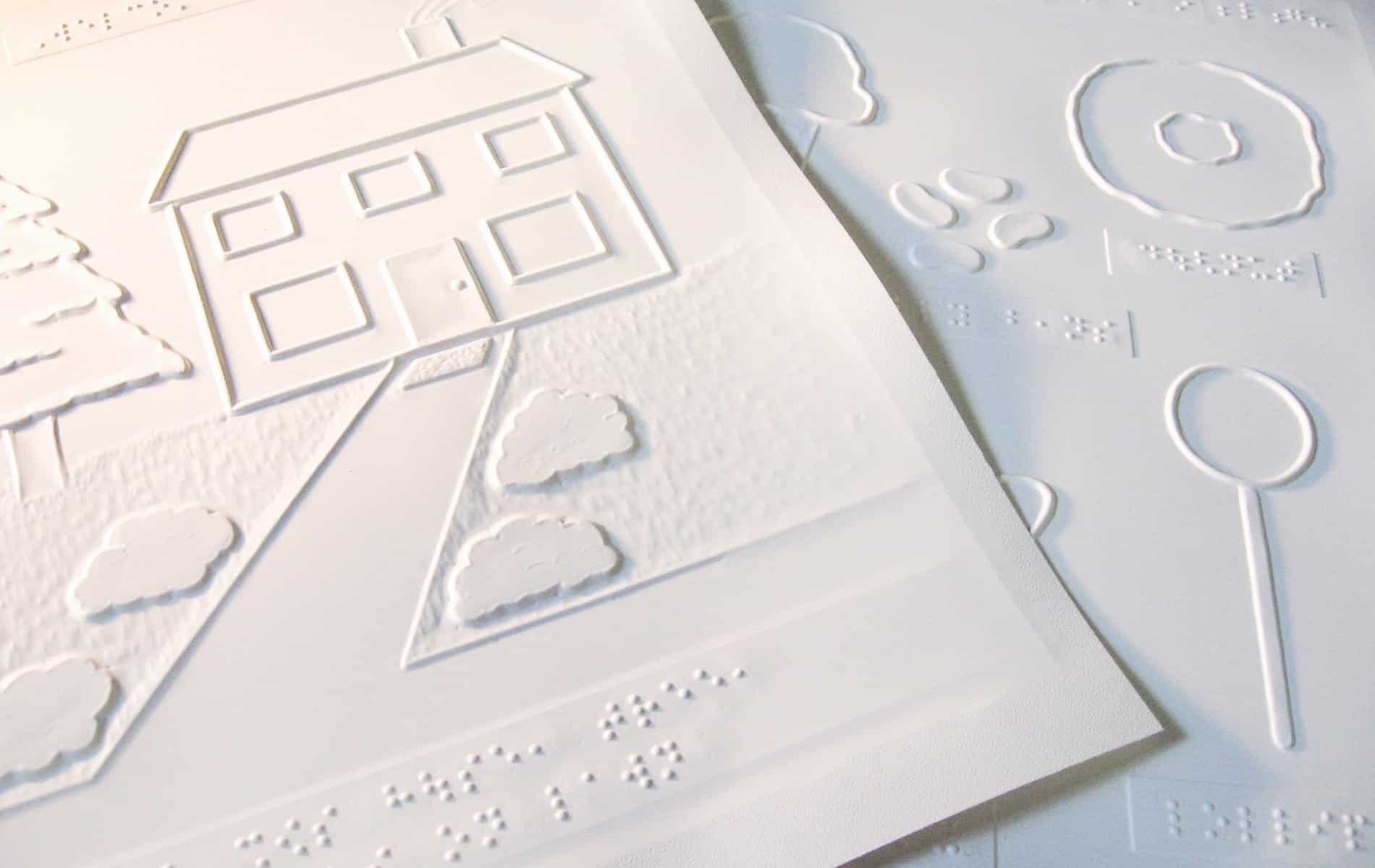

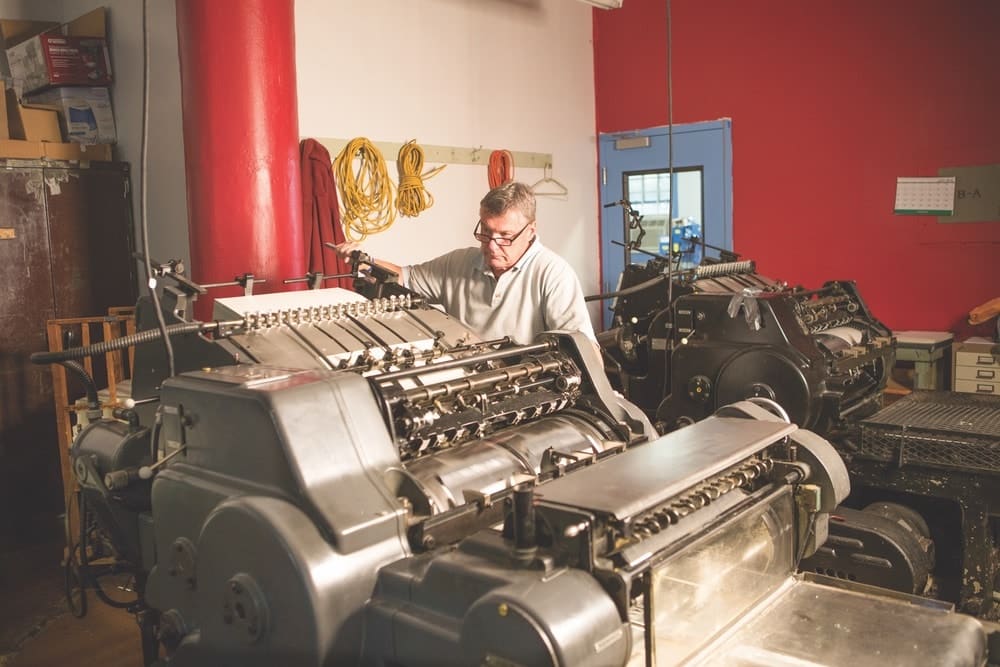

As print and braille documents are passed around the table, one can hear the heartbeat of the organization churning out pages in four-four time. It is the big embosser that makes NBP (National Braille Press) one of the few manufacturing enterprises remaining in the city. The press has occupied several facilities before arriving at this site, which formerly housed a piano factory. It is somehow fitting that the address is Eighty-Eight Saint Stephen Street.

Those deliberating as trustees during this late afternoon are in a tradition stretching back more than nine decades. It began with Francis B. Ierardi, the Italian immigrant whose goal in founding the National Braille Press was that blind people be able to read the newspaper. He realized this dream in the Weekly News with the assistance of Christian Herter and Richard E. Danielson, the publishers of Independent Weekly. They supplied carbon copies of the Week in Review to be transcribed into braille. Owing to its quality and the scarcity of such materials, issues of the Weekly News and its women’s journal, Our Special, were passed from hand to hand across America and internationally. In appreciation, Helen Keller wrote, “I am particularly glad to have the foreign news and the economic and political notes.” She continued on behalf of a truly underrepresented audience, the deaf-blind: “Above all I am happy that these two periodicals are finding their way to an increasing number of the deaf-blind. They mean more to us who are doubly handicapped than to others who only lack sight. Their enlivening pages restore to us as it were the aspects, colors, and voices of the light-filled world. They bear us over sea and land wherever we will, and we are free. Gone is the crushing weight of immobility and tedium! Our spirits rise light and glad in the thought that we can still think, read, write, and sometimes fill our hungry hands with useful work.” These sentiments prove timeless despite the profound change.

- The National Braille Press, headquartered in Boston, empowers the blind and visually impaired with programs, materials, and technology supporting braille literacy and learning through touch.

- The National Braille Press, headquartered in Boston, empowers the blind and visually impaired with programs, materials, and technology supporting braille literacy and learning through touch.

At this point, we can pose heavy philosophical questions: Is reading the same as being read to? Is hearing text, even in a familiar voice or the most sophisticated artificial vocalizer, the same as processing text through the internal voice with which we have all been born? No matter where you might stand on these and related questions, at a minimum braille affords a choice, an agency, and the possibility that a person with no or severely limited vision can read to others rather than always being read to.

Meanwhile, before the trustees begin putting final touches on plans for the annual gala, their chairperson is sharing a letter. The mother of a blind child is writing with gratitude and surprise after receiving a free ReadBooks! bag containing print/braille books, a braille primer for parents, braille alphabet cards, bookmarks, and other braille literacy tactiles. Living in a world of words where one’s hands are one’s eyes requires lifelong learning for parents and children alike.

Gone is the crushing weight of immobility and tedium! Our spirits rise light and glad in the thought that we can still think, read, write, and sometimes fill our hungry hands with useful work.”

As mom watches, her toddler is exploring a “bumpy book,” the same as the commonly circulated board books, but with braille labels so that the habit of touching text can be instilled. Later, there will be popular picture books using a multisensory approach—songs, tactile play, picture descriptions, body movement, engaged listening—all designed to promote active reading. And what of the blind parent or grandparent—should they be denied the treasured experience of bedtime story reading to a sighted child? Not at all! Because among the many reasons for so meticulously preparing for the annual fund-raising gala, A Million Laughs for Literacy, is what its proceeds fund—the Children’s Braille Book Club, which offers popular children’s books in a print/braille format for the same price as the print edition.

“Off to school” means standardized tests, math, geography, science books, and the French we took. As the trustees listen, the staff is making a series of presentations—on tactile graphics, tests produced, and maps acquired—all intended to maximize independent learning and minimize the demand for sighted assistance. After that, with the completion of formal education, other realities confront the blind at home, on the job, and in public. Am I really going to ask an overworked server to read me the menu when I’m dining alone? Am I always going to require directions when my industrial campus could be mapped? Am I going to eat a varied and healthy diet of my own creation, learn to use my iPhone, master the demands of a talking computer, enjoy the intimacy of reading good poetry to myself, compete in a poetry contest for braille readers of all ages, enjoy the playbill at a drama, and follow the text in a Mahler symphony? Can I send a valentine to a blind friend, perform on the job at the required level, and enjoy the leisure pursuit of good reading?

The National Braille Press, headquartered in Boston, empowers the blind and visually impaired with programs, materials, and technology supporting braille literacy and learning through touch.

The trustees of National Braille Press have formally adjourned after strategizing around answers to all such questions, but they’re taking time to trade stories of the past summer, to talk about local charitable foundations and the friends and associates who will be contributing handsomely to fund-raising at the gala, and to congratulate staff on their innovative thinking that keeps braille far from joining the ranks of dead languages. Outside the boardroom, the traffic is crawling in both directions on Huntington Avenue and Storrow Drive, but the pace of keeping braille relevant is relentless within these walls and beyond.

— V —

Material from the website of National Braille Press was used in preparing this article. Visit NBP.org to learn more. Thanks go to President Brian A. MacDonald and the staff of the press for their assistance and work on behalf of its clientele.

Nick Racheotes is a product of Boston public schools, Brandeis University, and Boston College, from which he holds a PhD in history. Since he retired from teaching at Framingham State University, Nick and his wife, Pat, divide their time between Boston, Cape Cod, and the rest of the Western world.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE