vie-magazine-july-2019-suzanne-pollak-column-jonathan-green-studios-hero-min

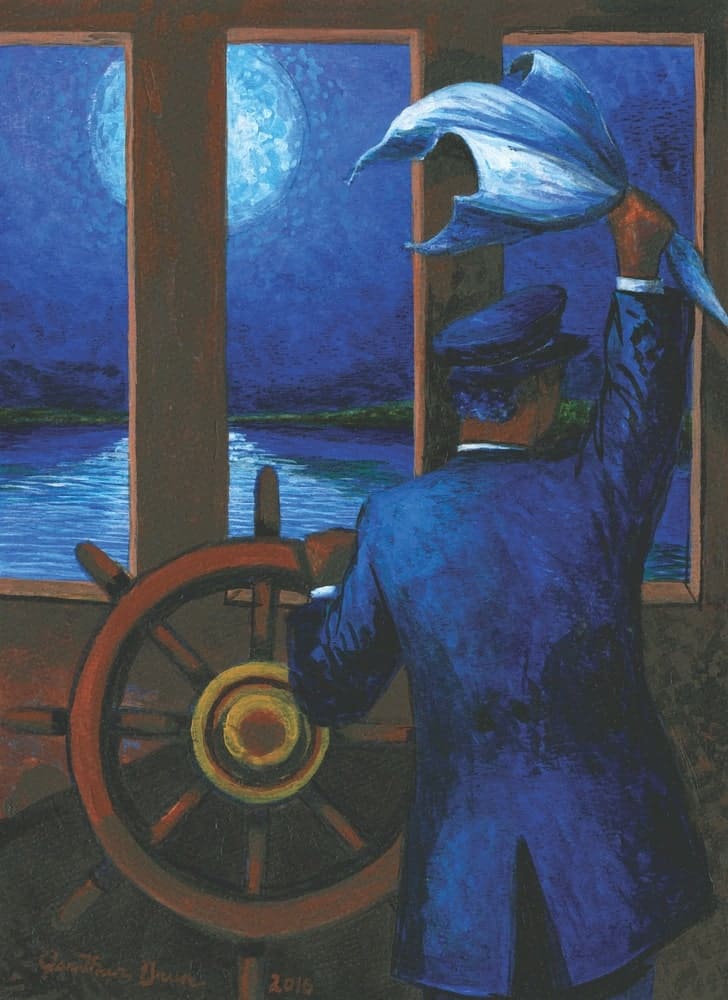

Distant Thoughts | Oil on canvas, 36 × 48 in., © Jonathan Green, 2002

An Authentic Voice

By Suzanne Pollak | Artwork by Jonathan Green

What makes very young people able to turn their passions into a living, marrying their gifts with the discipline to create their life’s work? How can they know so early, possessing the confidence and necessary focus to keep them on their path? I dreamed of being a painter but derailed in college, distracted by thoughts like If I am not Picasso, is it worth it? If my work is not going to hang in the Met, what does that say about me? If I am not ‘in,’ then can I still keep going forward and not give a damn what anybody thinks?

Jonathan Green knew in his very being the irrelevant nonsense of those distractions, which don’t mean a thing at the beginning of a career—or maybe ever. That’s why I love him. He actively chose to master one field (actually three: painting, fashion design, and the social graces) instead of being a jack-of-all-trades.

Just out of high school, Green escaped the tiny town of Beaufort, South Carolina, and headed for the Art Institute of Chicago, probably an unheard-of trajectory nearly fifty years ago for a gay African American man from a small, newly desegregated Southern city. Maybe those very issues made him fiercely determined to be the most prominent personality he could be. He spent four and a half years focusing on drawing and painting at the Art Institute. Immediately upon graduating he deemed himself a professional artist, and a brief conversation with master Jacob Lawrence taught him the best way to do that in three words: “Tell your story.” Green was smart enough to listen, take the challenge, and implement what he’d learned. He used his paintings to tell stories about his region, culture, and history, all in astonishingly original texture, color, and atmosphere. His paintings seem to sing.

In terms of inspiration, Green’s process has nothing to do with external factors. He is not copying anything, nor is he looking at photographs. He never pays attention to the art world, museums, galleries, or what anybody (with or without money) thinks. He is creating from his mind. His subjects are based on memories of growing up and observed details—in particular, things he wants to pull out of present reality and situate in his own creative bubble. If he is working on a painting of a woman, he might see someone walking down King Street in Charleston with the right silhouette, the perfect shape, and take in the details of the way her dress moves or how she relates to the scenery around her.

- Strolling by a Sluice Gate | Acrylic on archival mat board, 11 × 14 in., © Jonathan Green, 2013

Green’s subject source is family: their environment and history and, more broadly, the role and contributions of African American people in his low-country landscape. The community around Beaufort allows him to encompass the world. This subject matter is inexhaustible; it’s everything imaginable, representing all kinds of people. But the foundation of these universal themes is his home in the South Carolina Sea Islands.

Green arranges all of his work in a series of ten to thirty pieces, like chapters in a book telling a single story. He starts with a series of thoughts and ideas, then moves into drawings, then to watercolors. By the time he starts the canvases, he has already put in two-thirds of the thinking, the doing, the discipline. He is meticulous. When he is halfway into a series, he is already thinking of the next one and might spend six months researching in advance. He never waits on the muse. (He says he doesn’t even know what that is.) Green believes in the importance of strong energies and thoughts about what he is going to do next before he finishes a series. There is no downtime or waiting for something to happen next. He simply knows.

Green’s subject source is family: their environment and history and, more broadly, the role and contributions of African American people in his low-country landscape.

One series focused on his grandfather’s moonshine business. Green experienced making moonshine with this dominant male figure, but as a boy, he was more focused on taking in the scene—the birds, the clouds, the incredible colors at that hour in the morning when the sun begins to rise. The subject matter just happened to be his granddad making moonshine. His figures set up the mood, and his joyful, brilliant, bright shades of sky, water, foliage, and sand reverberate around them.

Green is currently working on a canoe series. He wants to talk about the creativity, spirituality, and economics of canoes by telling the history of enslaved people leaving the shores of West Africa in little boats that could not handle the waves. Other paintings in the series will depict imprisoned Africans around the Caribbean and their European captors cutting down any large trees so that they could not be made into dugout canoes for escape. Green feels if he doesn’t paint the story, then no one will retain the knowledge since so few people are reading these histories today.

- Robert Smalls | Acrylic on Arches archival paper, 14.25 × 10.75 in., © Jonathan Green, 2015

- South Carolina–based artist Jonathan Green

Monastic to the core, Green gets up early at four o’clock. He and his partner, Richard, socialize for an hour, drinking their tea and coffee and organizing their day. Richard is Green’s gatekeeper and makes sure that he doesn’t have to get involved with external things that take away from his art. Green pulls himself together personally for the next hour, and painting starts at six o’clock. From there, the concept of time is not part of Green’s world until his stomach sends the hunger signal. He and Richard break for a two-hour lunch, their main meal, and then it’s back to work. The only thing of any importance is completion; but even that is not important because Green believes if you are working on something every day, time is irrelevant, and the work will get done. His focus, energy, and vision are all about what he is doing and the subject matter on which he’s working; they’re not about anything or anybody else.

Green’s quiet elegance, strong sense of self, style, composure, and general ease are lovely. But make no mistake—he doesn’t care what you think about him. He is his own person with his own unique language. He interprets history, culture, community, and people in a way that is joyful, moving, and luminous. Few artists speak so authentically.

— V —

To learn more, go to JonathanGreenStudios.com or visit his gallery at 164 Market Street in Charleston, South Carolina.

Suzanne Pollak, a mentor and lecturer in the fields of home, hearth, and hospitality, is the founder and dean of the Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits. She is the coauthor of Entertaining for Dummies, The Pat Conroy Cookbook, and The Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits: A Handbook of Etiquette with Recipes. Born into a diplomatic family, Pollak was raised in Africa, where her parents hosted multiple parties every week. Her South Carolina homes have been featured in the Wall Street Journal “Mansion” section and Town & Country magazine.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE