vie-magazine-namibia-boat-safari-hero-min

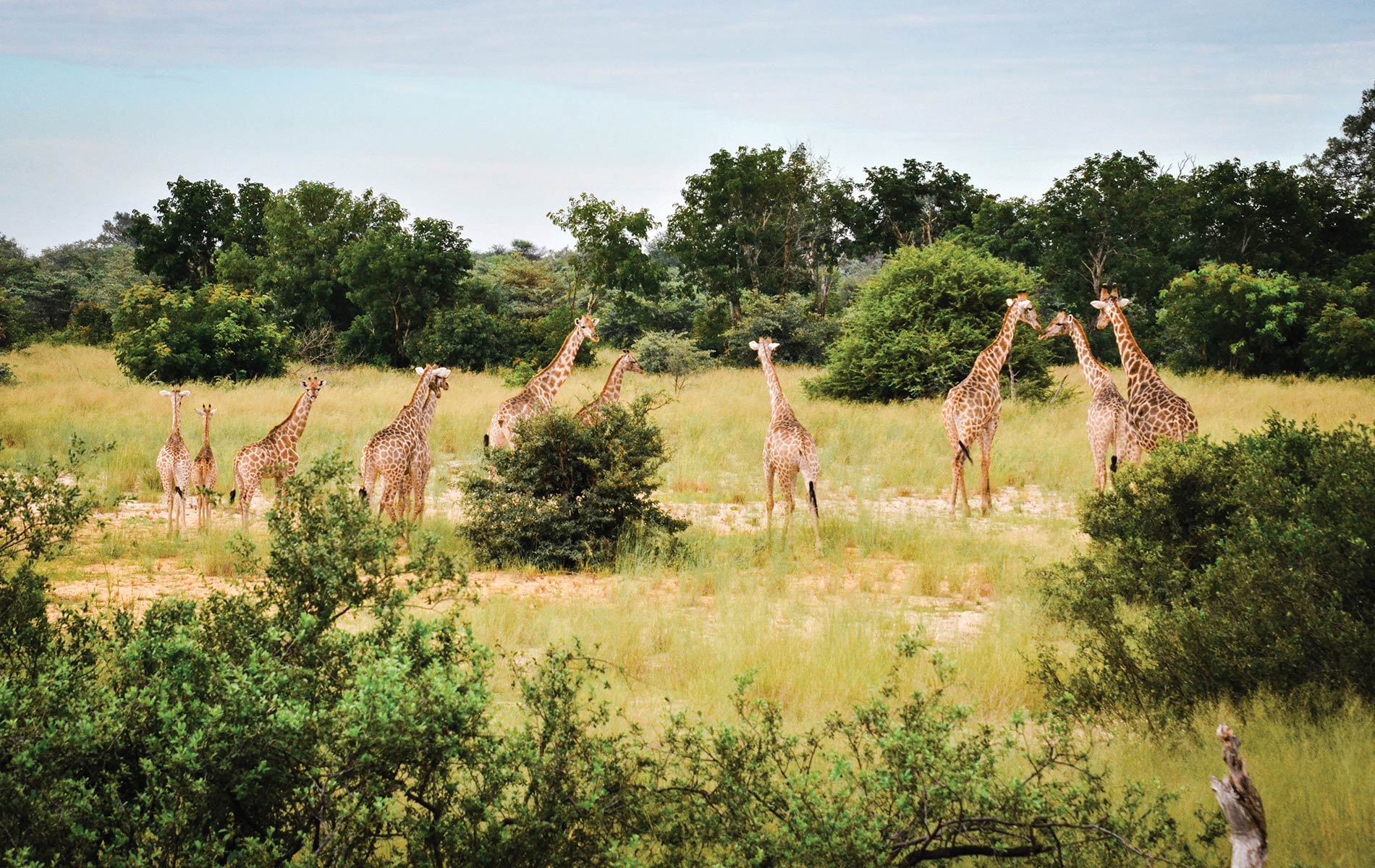

A tower of giraffes heads for their meal of choice—acacia trees—in Namibia’s Zambezi region.

Safari by Boat

Touring Namibia’s Zambezi Region

Story and photography by Kevin Revolinski

The Zambezi River flowed seven paces from the foot of my bed. I could have thrown a rock and hit Zambia from the back deck of my spacious cabin. The water moving past me would eventually tumble over the mighty Victoria Falls, a day trip from here. I had ten days in Namibia touring the Zambezi Region, formerly the Caprivi Strip, the narrow 280-mile-long protrusion of territory that extends from Namibia’s northeastern corner where it borders Angola, Zambia, and Botswana. Dubbed the Four Rivers Route, the safari starred the Zambezi, Okavango, Kwando, and Chobe Rivers and explored the lush lands in between, home to elephants, zebras, giraffes, hippos, and crocodiles, plus the occasional lion and over four hundred species of birds.

Children walking home from school along the highway waved at our passing safari jeep as our driver and guide, Rusten, delivered us from the regional airport to a boat to reach Zambezi Mubala Lodge. With a welcome drink in hand, I listened to my options: boat excursions in search of crocodiles, fishing for the long-fighting and fast-running tigerfish, and hikes into the grassy area around us to spy exotic bird species.

Namibia slips under the radar a bit. It’s the quiet neighbor to Botswana and South Africa, and only finally gained its independence in 1990. Once a German colony, Namibia’s roadways are direct and well maintained, making this nation, roughly double the size of California, the perfect African destination for independent travelers. Known best perhaps for its Skeleton Coast along the Atlantic—a land of dunes, shipwrecks, and surprising desert animals—and Etosha, a national park comparable to the classic African safari destinations of Kruger or the Masai Mara, Namibia has protected nearly 38 percent of its land. Much of what falls outside those boundaries is nevertheless natural and sweeps to the horizon. The human population is just over two million.

- Boat tours on the Four Rivers Route along the Zambezi, Okavango, Kwando, and Chobe Rivers are ideal for safari-goers to see wild animals such as hippos, hornbills, zebras, and much more.

- Boat tours on the Four Rivers Route along the Zambezi, Okavango, Kwando, and Chobe Rivers are ideal for safari-goers to see wild animals such as hippos, hornbills, zebras, and much more.

My next stop was Camp Kwando, named for the river running past the property. The most rustic of my stays, the resort offered cabins with screened windows open to the night sounds of insects, frogs, waterbirds, and even a distant lion’s roar. A loud, guttural grunting, deep from a cavernous throat, awakened me in the middle of the night. I was fight-or-flight awake and knew it could only be one thing: a hippo. Assuring myself that hippos can’t climb deck poles, I grabbed my phone to try to capture its call on audio. I stood at my screen door, the world around me as black as oil but the heavens showing a riot of stars. I listened to the river slipping through the reeds along the bank. And again I heard a single exclamatory grunt and then the low grunting pattern like the evil laugh of a villain—Jabba the Hutt comes to mind—so loud that I nearly dropped the phone; the hippo wallowed right under the edge of the deck. I listened to it roll a bit in the water, the rippling along its invisible hulk, and after a lengthy silence, I knew it had moved on.

A loud, guttural grunting, deep from a cavernous throat, awakened me in the middle of the night. I was fight-or-flight awake and knew it could only be one thing: a hippo.

The next day, on an aluminum boat with an outboard motor, a guide ferried a group upstream to find a bloat of thirty hippos along a bend in the river. They stood on the river bottom, all of them staring, only their eyes and those amusing, tiny, cuplike ears above the waterline. Our guide slipped the boat into a grassy area along the bank no more than twenty-five feet away. Another hippo rose up out of the river, mouth wide to show some jagged teeth. This was the deadliest mammal mouth in Africa. Lions? Less than a hundred people per year fall to the king of the jungle. Hippos—territorial, sharp-toothed, and weighing in at 3,300 pounds—kill more than five hundred annually.

We lingered long, the light shifting as pink clouds reflected on the water, and then turned back for the lodge, stopping halfway back when we came across two male elephants. Their tusks clattered and trunks tangled as they threw their weight against each other in a challenge for supremacy.

While many of my excursions occurred on the water, land-based game drives didn’t disappoint either. In Mudumu National Park, we spotted elephants, hippos, and impalas, and the Mahango Game Reserve impressed with its giraffes, crocodiles, baboons, wildebeests, ostriches, and abundant herds of antelope and zebras.

- A herd of impalas stands at attention.

- Boat tours on the Four Rivers Route along the Zambezi, Okavango, Kwando, and Chobe Rivers are ideal for safari-goers to see wild animals such as hippos, hornbills, zebras, and much more.

- The flora on the Four Rivers Route is just as magnificent as the fauna.

- A glorious sunset on the Okavango River.

Days later and another river over, I checked into Divava Okavango Resort and Spa. Dining on the deck overlooking the Okavango River, I could hear the cascading Popa Falls nearby, and upriver in the distance, a cluster of gray rocks in the water moved and revealed themselves as hippos. Expansive thatch-roofed rooms high along the riverbank offered outdoor showers and tubs looking out to the water.

That afternoon, I joined a visit to a village just outside the lodge. Our guide, a resident, walked the group through daily life there. The villagers gathered under a tree and began singing and drumming, forming a dance circle. This dance was not a shuffle or a measured step, but the leaping and stomping of letting loose, smiles on their faces, taking turns. This wasn’t a hotel floor show. They finished, and we thanked them, wandering deeper into the village with our guide. As soon as we were out of sight, they started singing again off in the distance, for themselves, for the love of it. This was the second of two village excursions, and by this point the number of locals I’d met far outnumbered the travelers I’d encountered that week. Back at the lodge, I struck up a conversation with a German couple who had been coming to Africa for years, specifically to Namibia for the last six. I noted the scarcity of tourists, and the woman nodded with satisfaction. “Botswana is too expensive now. And so many people.”

Only the joyous welcome of singing and dancing from the entire staff could follow that display, and after dinner I retired to my cabin, the melodies still ringing in my ears. This is Africa.

My final two nights were back on the Okavango at Hakusembe River Lodge. The previous day’s sundowner cruise had put me nearly an arm’s length from a variety of bird species perched and posing for the camera: giant kingfishers, African darters, two species of herons. We toasted the sunset, sipped champagne, and then returned to the beach, where the entire staff of the resort greeted us in song and drumbeats next to a fire. That final day had been rainy on and off, the sky seemed low and leaden, and the chill was enough for me to need a windbreaker. A visible sunset seemed unlikely, but I decided to go the full mile and book one last sundowner cruise. We encountered more birds, paused to hop off the bow onto the Angola side of the river just to say we did it, and had another round of champagne.

A male African darter perches on a branch near the river.

The boat turned to head back, and then magic happened. A golden crack opened up on the sullen horizon, and marmalade warmth began to spread from the west. The smooth water mimicked it until the light had scattered overhead and at our feet, and the whole world appeared as if through a rosy filter. Then the sky to the east took up the color as well, and sunset simply went over the top and lit up part of a rainbow behind us. Even craning my neck around I couldn’t take it all in, and my camera never stood a chance. When all the golden glow had faded through pink and then to purple, we returned to shore. Only the joyous welcome of singing and dancing from the entire staff could follow that display, and after dinner I retired to my cabin, the melodies still ringing in my ears. This is Africa.

— V —

Blue Crane Safaris offers this multiriver trip, coordinating all transportation, bush plane fly-ins, and guides while booking lodging with Gondwana Collection along the way. Visit BlueCraneSafaris.com and Gondwana-Collection.com to learn more.

Kevin Revolinski is the author of several books, including The Yogurt Man Cometh: Tales of an American Teacher in Turkey. He also writes online at TheMadTraveler.com.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE