vie-magazine-alzheimers-hero

In a World of Questions

Love Is the Answer

By John Thorndike | Illustrations by Suva Ang-Mendoza

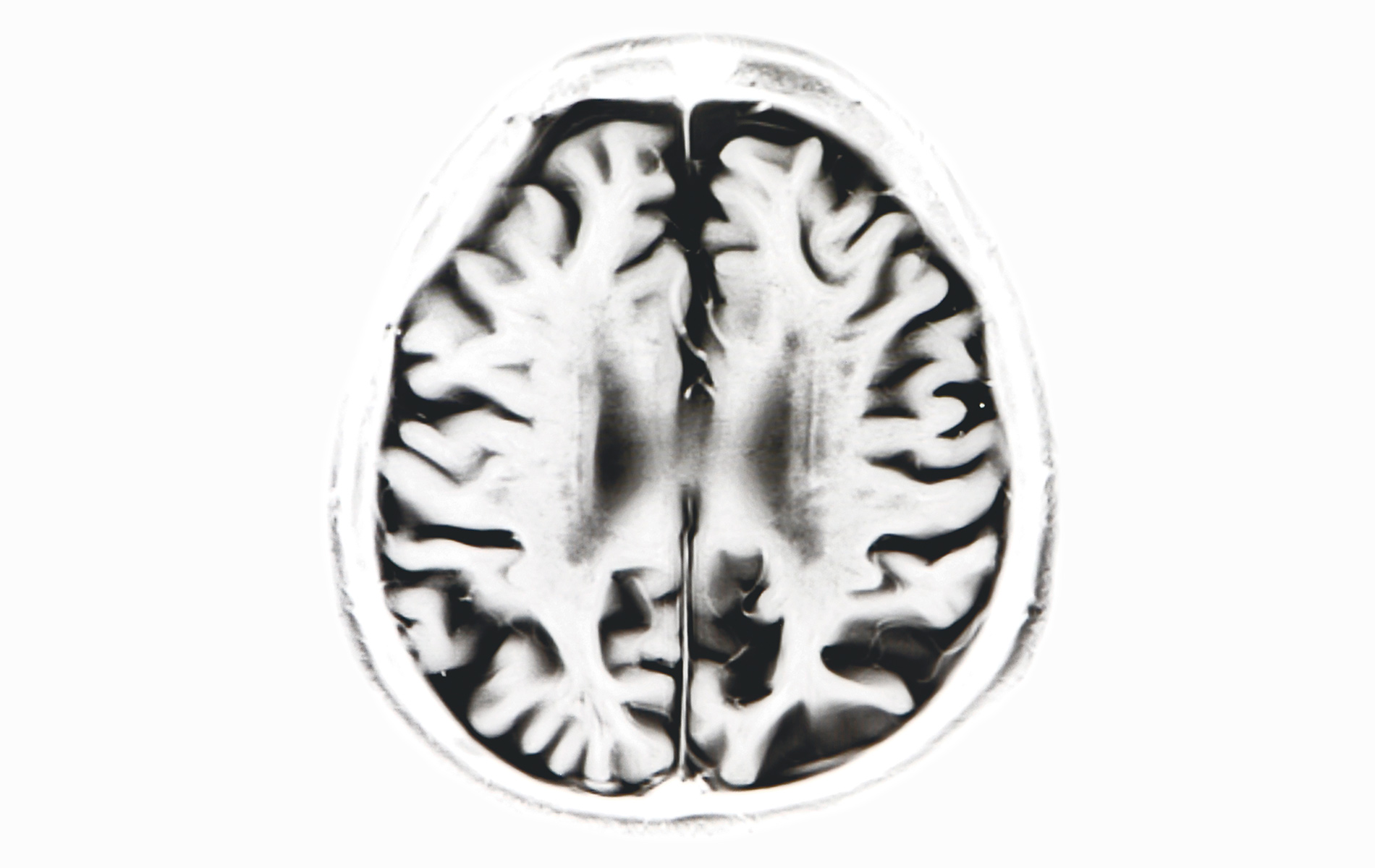

In early 2005, as my father’s dementia grew worse, it seemed unlikely that he would live out his days at home. All talk was to the contrary. A neuropsychologist, after diagnosing “advanced second-stage dementia, most likely caused by Alzheimer’s,” urged me to investigate the memory care units at local nursing homes. There, he explained, was where an Alzheimer’s patient would almost certainly wind up, once his family could no longer take care of him.

The psychologist was an expert with a PhD. His specialty was dementia; he ran a memory center on Cape Cod, and clearly, he was familiar with both the progression of the disease and the difficulties of caring for such patients. “He’ll have good days and bad,” he said of my father, “but in the end, if he lives long enough, he’ll forget everything.” Well before that, he would have to be moved to an institutional home.

Both my brothers believed the same thing. The time was coming, they felt—and soon—when care for our father would be more than we could handle.

I wasn’t sure. At the time of his diagnosis, Dad couldn’t remember the day of the week, could only name one recent US president, and couldn’t spell “world” backwards. But he could still shower and use the bathroom by himself, and he could still carry on a logical but limited conversation. For now, at least, I wasn’t going to move him into a nursing home. I knew this because only months before he’d made it clear to me that he wanted nothing to do with such places.

In the fall, I’d taken him to visit one of his oldest friends, Oliver Jensen, who was slowly forgetting everything, in a Connecticut nursing home. On the day we arrived, Oliver was alternately cheerful and confused. His room was large and bright, but there was almost nothing in it. There were no books, not even the books he had written himself while working with my father at the magazine they started, American Heritage. Oliver was belted into a wheelchair and could not go outside on his own. He knew my father, and perhaps, he knew me, and he seemed glad to see us. But periodically, in the midst of our conversation, his head would drop onto his chest, and he he’d go to sleep. Waking a few minutes later, he would repeat his initial greeting: “So, where have you two come from today?”

If this unnerved my father, I couldn’t see it. Nor did he respond when some woman down the hall started screaming. For fifteen minutes, she screamed and went silent, screamed and went silent. Oliver didn’t seem to notice either, but to me, it sounded like bedlam. Someone was in physical or emotional pain, and could nothing be done about it?

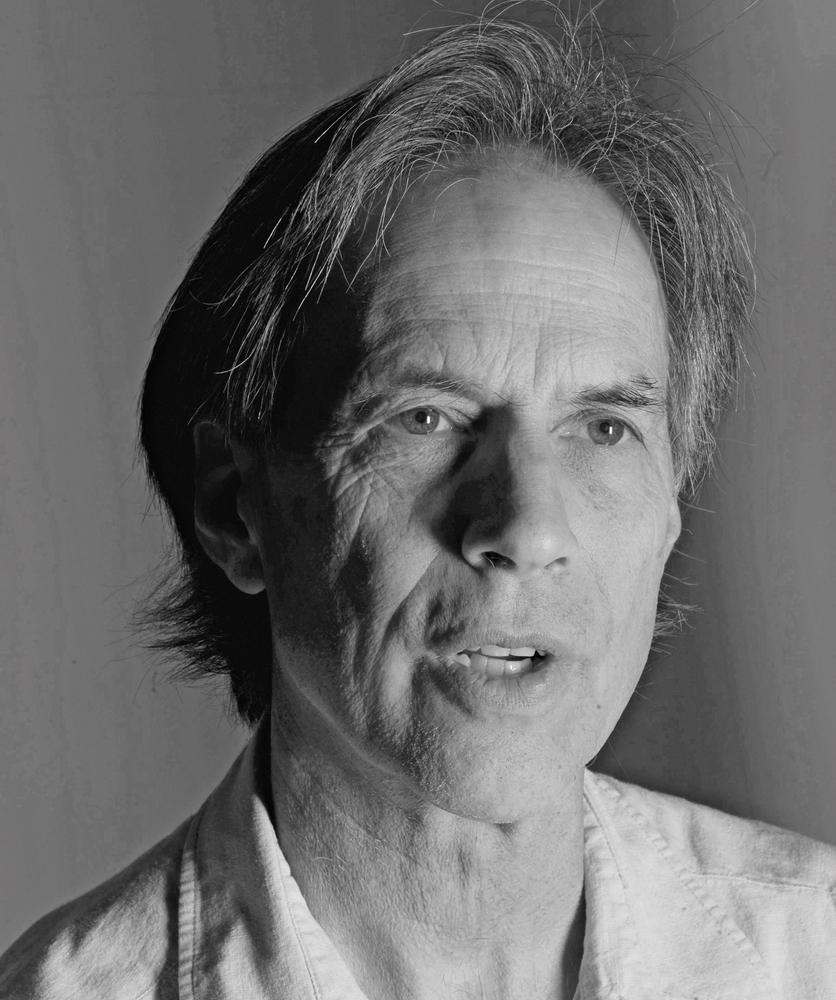

Author John Thorndike and his father, Joseph J. Thorndike

After ninety minutes, my dad and I took our leave, passing the double row of wheelchaired patients inside the building’s front door. Almost all of them were old, some looked ancient, and many stared as if into a void. Once outside, my father hobbled across the parking lot to our car, looking more bent than when we arrived. For ten minutes, as I drove, he slumped in his seat against the car door. Then he gathered himself, sat up straight and said, “Don’t ever put me in a place like that.”

And my father needed me—my father who had done so much for me my whole life and almost never asked anything in return—just that one stark plea: “Don’t ever put me in a place like that.”

According to the AARP, 90 percent of US seniors want to spend their last years at home. It’s what I’ll want, I’m sure, and it’s definitely what my father wanted. The previous summer, after watching the first signs of his confusion, both my brothers offered him a place to live. But he didn’t want to move to Vermont or Virginia; he wanted to stay in his own house. That was why, following a troubled Christmas, I left my own home in Ohio and moved in with him on Cape Cod.

Neither of my brothers could have made such a move. One had a busy law practice, the other a teaching job and a two-year-old daughter, and both were married to women who also had jobs. I was single. I’d spent the last few years building houses and was now renting out eight of them, but I knew I could find a friend or agent to take care them. I was available, and my father needed me—my father who had done so much for me my whole life and almost never asked anything in return—just that one stark plea: “Don’t ever put me in a place like that.”

Though barely aware of it at the time, I had another motivation. Thirty years earlier, I had not looked after my mother when she had been desperate, and she had died alone, at the age of fifty-seven, on the floor of her New York apartment. There were reasons for my negligence: I had a two-year-old son, my wife was descending into schizophrenia, and I was living half in the United States and half in Central America. Family life is complex, with money, time, and emotional inclination all playing a role when it comes to looking after our parents. However, from my father, I’d had a direct request.

I remember the low-level panic that gripped me on my first nights at his house, as I lay on one of my grandparents’ horsehair mattresses. “I’ve been here two days,” I thought; “I’ve been here three days.” Instead, it felt like weeks or months. Here, time would stretch out without my friends, without volleyball, tennis, and dancing. This year I would plant no garden, and travel nowhere. I’d known all this was coming, but it was still a shock.

At the same time, looking after my father was easy, at least at the start. For over thirty years, he’d taken care of himself, and he didn’t like to think I’d moved in because he was failing. Between us, for months, we sustained a small falsehood about my stay, pretending that I was only there for a visit. I cooked for him; I took care of his meds; I took him to his doctor, dentist, and podiatrist appointments, and at night, we watched the news or sometimes a movie, until television no longer made sense to him.

I became aware, over those first months, of how many things helped make the job easier for me:

The fact that he was ninety-one. What, I thought, if he’d been twenty years younger? I had a friend whose father was in his early seventies and thought his wife was a woman he’d hired to clean his house and cook his meals. The care for someone that age, newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, could easily go on for a decade or more. No, my father was already old, which put a probable cap on how long I would have to look after him.

Support from my brothers, especially the one who was a lawyer. He took care of all legal and financial matters, which relieved me of a huge burden.

Money. My brothers had agreed to pay me, out of my dad’s account, $1,000 a week. This was more than I’d ever earned in my life, and whenever some resentment surfaced about my seven-days-a-week schedule, this paycheck soon calmed me. We’re supposed to care for our loved ones because it’s the right thing to do, but I was always aware of how much that salary helped. I was also aware of how most caregivers do not get paid, or paid enough, for all they do.

Dementia can thoroughly change a patient. My dad grew confused, but he was rarely angry or resentful.

Recognition. Though I pretended otherwise, I liked telling my friends back in Ohio or people I met on the Cape that I’d given up my own life to look after my father. The truly enlightened caregiver might never consider what other people think. Who among us is so pure? There were plenty of small lost moments when I was buoyed by the approval of others.

My father’s gentle nature. Dementia can thoroughly change a patient, and after talking to hundreds of caregivers over the last ten years, it seems to me the luck of the draw as to which patient will prove calm and polite and which will start insulting or even thrashing those close to him. My dad grew confused, but he was rarely angry or resentful.

Can you see what an easy time I had of it compared to how it might have been and compared to how it is for many caregivers? I’ve been humbled, over and over, by how many have spent five, ten, or fifteen years caring for someone with severe dementia or some other debilitating condition such as Parkinson’s, MS, Lou Gehrig’s disease, cerebral palsy, and others. Millions of people sacrifice, every day, to keep family members out of facilities they don’t want to be in.

Was it worth it? It was for me, though I could not have guessed the rewards beforehand. It was much like child-raising, a job that sometimes threatened to crush me when my son was young, but that later seemed the vital center of my life. (I was lucky not to be one of the “sandwich generation,” taking care of both children and parents at the same time.) Without my father’s decline, I might never have grown so close to him.

I might never have learned to touch him. From my teenage years on, our only touch had been handshakes. Dad came from a restrained New England family, and as I grew up I adopted the same reserve. In the sixties and seventies, as the world loosened up, my brothers and I had begun to hug Dad briefly when we greeted each other or parted. I’m sure that, if it had been up to him, we would have kept it to handshakes—but now, as his dementia and other infirmities grew worse, I helped him dress and undress, helped him in and out of the shower, and helped him onto and off the toilet. I shaved him, I cut his hair, and eventually, I had to clean his bottom. Like all of us, I had feared that job, but when the time came, how simple it was. My brother, no more adaptable than I, learned how to do it overnight, after he took over Dad’s care for ten days, close to the end of his life.

If my father had spent his last days in a home, how much I’d have missed.

I would probably never have pored through all of his letters, papers, and clippings. He had saved close to ten thousand letters, many of them sent to him, others the carbon copies of letters he’d written and mailed. I read, or at least glanced at, every one of them and learned much about his past as well as a little about my mother.

Before Dad’s nouns fell away, we talked. He told me stories about his years at Life magazine, about the nights he’d spent at Anzio with shells passing overhead like freight trains, about our ancestor who was hanged as a wizard during the Salem trials.

I was able to see that even when deprived of language and memory, even when he couldn’t focus or respond, he was still my father. The vital elements were woven through him: his gestures, his expressions, the occasional and miraculous eruption of a full sentence, or two, or three in a row! This was not some random old man. This was my father, and while at the end he might not have known me, I always knew him.

[double_column_left]

Author John Thorndike

[/double_column_right]I was able to see that even when deprived of language and memory, even when he couldn’t focus or respond, he was still my father.

In the evenings, through the long middle stretch of his dementia, I read to him. I read Lieutenant Hornblower and The Wind in the Willows and The Story of Babar, each book simpler than the one before. These restful sessions were the highlight of my day, just as they had been with my son when he was growing up.

Very little of this would have happened if my father had been living in a home. Over the years, I’ve been in plenty of nursing homes and rehab centers. I was in one last week, visiting a friend who’s recuperating from cancer surgery. The nurses and attendants in these places might be doing their best but, to be blunt, it’s not enough. Their touch cannot carry the same affection. They don’t have the time to sit down and read or talk to their patients. They don’t know their histories. There is never enough staff, and they’re hopelessly busy. What you hear on most wings is television, with the sound of a half dozen sets reverberating up and down the hall.

Halfway through my year on Cape Cod, I called Dotty, a woman who had worked for Oliver Jensen and who still visited him almost daily. She told me how short-handed they were at his nursing home, how they never took him outside, and how they didn’t brush his teeth. She told me she had gone in one morning at eleven and found him lying in his own diarrhea, and how thirty minutes passed before she could get some reluctant help. “Everyone’s in a hurry,” she said. “The feeding room is the worst. I hate to go in there. They purée the food and spoon it in too fast. There’s always somebody coughing or choking.”

Her conclusion about such homes: “I pray to God I won’t have to go into one of those places.”

I am never going to judge those who wind up putting a parent or spouse in a home. Some cases are simply too difficult, and some caregivers too exhausted. Or even simpler, they don’t want to go on immolating their lives on the altar of doing the right thing. Each person has his own story, her own situation, his own abilities. Home care is not for every caregiver nor every patient. I only want to say that it’s often more feasible than we imagine.

Above all, I don’t advocate for doing the job by yourself. Indeed, from both relatives and professionals, the most common piece of advice you’ll hear is, “You can’t do it alone.” This is especially true as a patient becomes less mobile, can’t make it to the toilet, can’t walk at all. But you don’t have to do it alone. Visiting nurses, physical therapists, counselors, and attendants can help. And since the advent and spread of hospice, even dying at home has become a reasonable choice. That’s what I wanted for my dad, and what he wanted for himself. And we were not alone in this: for while 60 percent of us still die in acute care hospitals and 20 percent in nursing homes, 80 percent of Americans now say they would prefer to die at home.

Because I was living with him, my dad died in my arms. This was partly by chance, of course, for any morning I might have gone downstairs and found him lying cold in bed. But, as usually happens, I knew his death was coming. The hospice nurse and aides all knew, for we’d watched his decline over the most recent weeks. For three days, he’d neither eaten nor drunk. Propped up in his hospital bed, he had barely moved in the last twenty-four hours. Still, I didn’t spend every minute with him, and it was somewhat by chance that I went into his room when I did and stood beside him. I put a hand on his chest to feel his heartbeat, and two minutes later, I still had it pressed to him when his heart stopped beating.

I put a hand on his chest to feel his heartbeat, and two minutes later, I still had it pressed to him when his heart stopped beating.

I was glad not to share the end of his life with people who hardly knew him. I was glad, too, that we were not in a home or hospital where I’d have felt constrained. Instead, with just the two of us in his house, I climbed onto his bed and took him in my arms. I embraced him in death as I never could in life—a thought that soon pitched me into the deepest sobbing, loud and shameless.

Dad died around nine in the evening, and I held back from calling hospice until the next morning. I called my brothers, I called my son, and I called a few others, but I wanted more time with my father before the men in black coats came, before they transferred him into a zippered bag and removed his body.

Over and over during that year, my family helped me. Hospice helped me. The local Alzheimer’s Association, the senior center, a woman who came every day so I could get two hours at the local library—many people helped me. I did not do it alone. But to this day, I am hugely grateful that I did not put my father in a place like that. He wanted to live in his own house and die in his own house, and that was the right choice for both of us.

— V —

John Thorndike grew up in New England, graduated from Harvard, received an MA from Columbia, and then spent two years in the Peace Corps in El Salvador, as well as time in Chile and Guatemala. In 1972, he returned to the United States with his son and settled in southern Ohio. For ten years, his day job was farming. Then, it was construction. He is the author of two novels, Anna Delaney’s Child and The Potato Baron, as well as a pair of memoirs: Another Way Home, about raising his son after his wife developed schizophrenia, and The Last of His Mind: A Year in the Shadow of Alzheimer’s.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE