vie-magazine-modern-architecture-robert-davis-seaside

Seaside in 1997 before the completion of Central Square shopping district. Photo by Steven Brooke

High Design – Form Follows Function

By Susan Vallee

Robert Davis, town founder of Seaside—the architectural gem that sparked the New Urbanism planning movement—likes to say that he was “marinated in modernism.” He became a developer almost by accident. Robert had recently graduated from Harvard Business School, and he and his friends were lamenting the lack of affordable housing when an idea was sparked; they would buy relatively less expensive land zoned as infill, build a small, compact project, and each person would take two units. Robert found a great parcel of land in Coconut Grove, Florida, and bought it, but somewhere along the way he lost his business partners. “No problem,” he thought. He would undertake the project by himself in his spare time. He now laughs at the idea. “I, of course, was not realizing that with a smaller project you had to do everything yourself, whereas, with a large project, you can contract the work out.”

But he finished it, dubbed the project “Serendipity,” and, after selling units, began to look for his next project. “Apogee” would also be located in Coconut Grove, but for this one Robert was inspired to take a few additional risks.

“The houses were more interesting and radical,” he said. “They were the international modern aesthetic with lots of light and space. They were the ultimate bachelor pads.” Robert and his then-girlfriend (now wife), Daryl, moved into one of the units. At the time, Daryl was completing her master’s degree in psychology and community counseling at the University of Miami and working in the field of child psychology.

Designed by Machado and Silvetti Associates, the Machado-Silvetti Building combines Robert’s vision of traditional architecture. Circa 1997. Photo by Steven Brooke

While coordinating a photo shoot of Apogee for House Beautiful, Robert and Daryl were introduced to a young couple, Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, who worked at the renowned firm Arquitectonica. A quick friendship was made and long conversations about how architecture and planning impact people’s lives began.

“Robert was always interested in high design,” Elizabeth said. “We (Andrés and I) were designing houses and small commercial buildings, but no urban design. That was the recession of the 1970s. We were spending our time with Robert, not being paid, because we were very interested.”

Andrés has been quoted as saying, “One day, I went to a lecture by Léon Krier, the man who designed the English model town of Poundbury for the Prince of Wales. Krier gave a powerful talk about traditional urbanism, and, after a couple of weeks of real agony and crisis, I realized I couldn’t go on designing these fashionable, tall buildings that were fascinating visually but didn’t produce any healthy urban effect. They wouldn’t affect society in a positive way. The prospect of, instead, creating traditional communities where our plans could actually make someone’s daily life better really excited me. Krier introduced me to the idea of looking at people first and to the power that physical design can have on changing the social life of a community. And so, in a year or so, my wife and I left the firm and went off to do something very different.”

“We learned a lot from that Cracker house,” Robert said. “It followed the modernist mantra of ‘form follows function’ in every way. And, you know, we didn’t mind that it wasn’t air-conditioned.”

Robert’s experience with designing and building Serendipity and Apogee, the tours of small Italian towns with Daryl, and the delightful simplicity of the Cracker cottage they called home, all led him to wonder whether they couldn’t do something really interesting with a parcel of land in the Florida Panhandle. He had spent summers vacationing in nearby Sunnyside Beach as a youth, his family renting simple little beachfront cottages with screened-in porches. He wondered whether one could successfully combine traditional and modern architecture and create a town in which people were excited to live.

Photo Courtesy of The Seaside Institute. Town sign in early 1980s. Seaside’s population fluctuates with the seasons— locals used to count the dogs, too.

Andrés and Elizabeth began planning Seaside, drawing on Léon for his expertise and insight (it was Léon’s idea to create sand footpaths throughout the town). Then Robert approached Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti of Machado and Silvetti Associates and Steven Holl to design two buildings in downtown Seaside (dubbed the Machado and Holl Buildings).

“The Machado was much more successful in the effort,” Robert explained. Now home to retail and office space with condos above, the blue and gray buildings are ubiquitous to Seaside.

Commissioning these architects at such an early stage in Seaside’s development exemplifies Robert and Daryl’s faith in the project and their appreciation of fine architecture. Years later, Time magazine would declare Steven Holl “America’s best architect,” while Machado and Silvetti Associates would be recognized by the American Academy of Arts and Letters for 20 years of “boldly conceived work.”

As the town began to take shape and the first homes were built, Robert and Daryl tried everything from hosting a produce market to weekend parties on the beach—anything to entice people to spend a few minutes learning about what Seaside planned to become. Daryl began taking drafting classes at a nearby community college so she could help with the planning and design efforts and evolved her produce market into a (more popular) clothing bazaar.

As more people began to learn of Seaside and as the town grew, Andrés and Elizabeth began spreading the message of the “New Urbanism” through the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU), which the couple helped to cofound in 1993. Dubbed one of the most important architectural movements in the past fifty years by the New York Times, the CNU boasts more than 3,000 members and urges members to address community, environmental, health, economic, and design issues through urban design and planning.

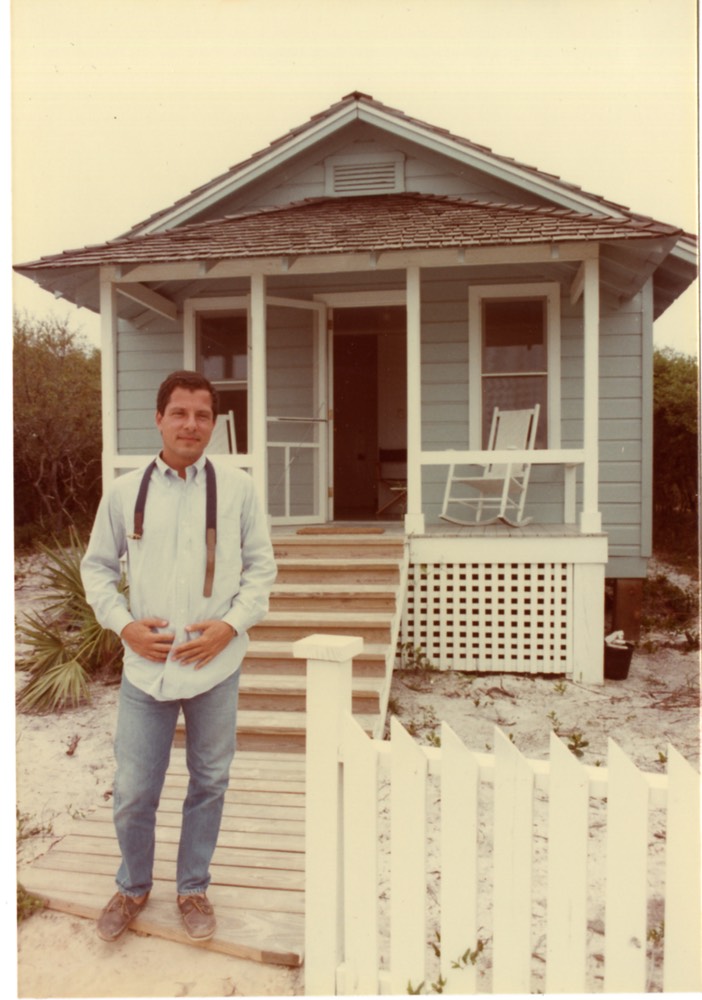

Photo courtesy of The Seaside Institute. Architect Andres Duany in front of the town’s then planning hub, early 1980s.

It is a philosophy that pits fans of modern planning against the New Urbanism model of planning. Robert said he differentiates between modern architecture and modern planning in his discussions, but admits that traveling scholars and past Seaside Prize recipients might not.

“Léon Krier is really an anti-modernist,” he said, yet the two recently embarked on a tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work in Chicago.

“Wright and Le Corbusier (a pioneer of modern architecture) built some of the most beautiful buildings that have ever been built,” Robert said. “Where they really were dead wrong was the planning ideology. They hated the city. Corbusier wanted to tear down Paris and replace it with large buildings and a grand boulevard. Wright conceived of Broadacre City, where you had one-acre lots and you had to drive to them.”

Seaside urges developers and builders to utilize New Urbanism planning concepts in their designs through the nonprofit educational arm of Seaside, The Seaside Institute. Each year, The Institute invites traveling scholars, architects, and artists to the town and awards the coveted Seaside Prize to those encouraging and practicing New Urbanism concepts. If you look closely in Seaside, you’ll find touches of modern architecture in Ruskin Place and a few homes within the town. It is a mix that seems to occur organically, depending on the owner’s personal tastes and styles.

Key pedestrian axes to the Gulf are defined by prominent architectural components seen from this photo from 1997.

Photo by Steven Brooke

“The image of Seaside is that of a Southern coastal town,” Elizabeth said. “But it is an American-style vernacular.”

Maybe that is why the town has so entwined itself into the hearts of thousands from across the globe. Within the town of Seaside we see the American dream, the utopia where we all want to spend a few minutes talking to a new friend or delighting in a grandchild who discovers the squeaky, white sands for the first time. It is a place of respite and renewal. As the town continues to evolve, new memories and new experiences will be made. And—the town planners hope—it will continue to inspire others to think harder and dream bigger.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE