vie-magazine-lee-crum

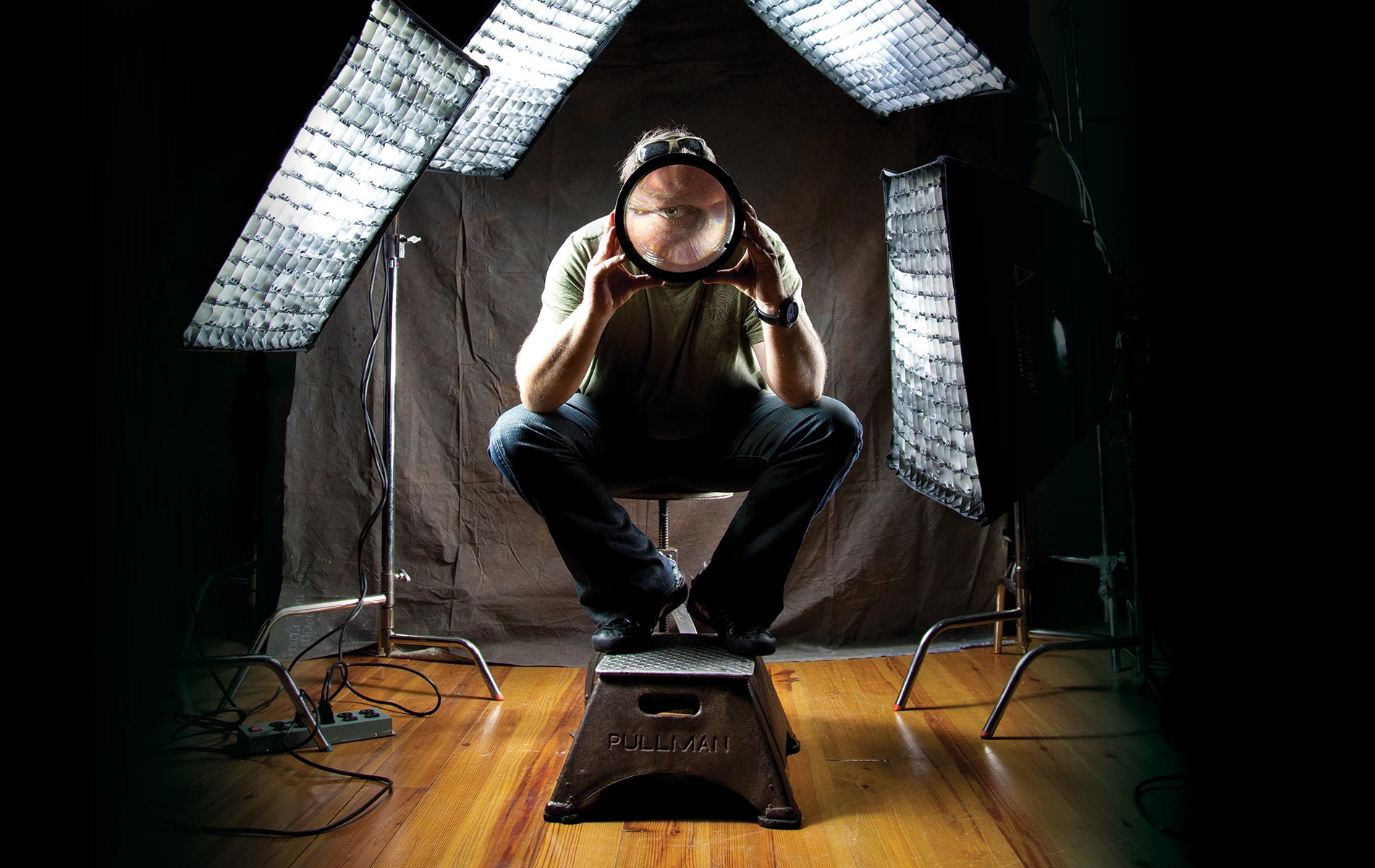

Eye of the Beholder

By Sallie W. Boyles | Photography by Jake Meyer

Beauty, creativity, emotion—these are in the eye of the beholder. With his camera, photographer Lee Crum illustrates what his eye beholds. Emeril Lagasse, Justin Timberlake, and Eli and Peyton Manning are just a few of the people he has photographed, but his portfolio does not stop there. Crum doesn’t just photograph people; he portrays them as they truly are. Whether photographing Jack Nicholson, Sean Connery, or for a Starbucks ad campaign, he captures the essence of his subject. Mark Twain once said, “You can’t depend on your judgment when your imagination is out of focus.” It is evident Crum’s imagination is not out of focus. As a photographer and an artist, Crum’s vast career brings to light what is truly in the eye of the beholder.

Lee Crum’s studio and the headquarters of VIE – People + Places are practically neighbors, but publisher Lisa Burwell learned about the accomplished photographer in a roundabout way. Jake Meyer, a local photographer who works on assignment for the magazine, had posted a sample of Crum’s work on his Facebook page. The heart-shaped collage of photography mixed with graphics and handwriting created for a Starbucks ad caught Burwell’s attention, so, when Meyer, along with another colleague and friend, suggested spotlighting Crum in VIE, Burwell was ready for her readers to meet the gifted man behind the camera.

“Our area attracts creative artists from around the globe,” says Burwell. “And people like Lee are testament to the talent found in sleepy Grayton Beach.”

In turn, Crum appreciates the nod, if only to confirm that people are connecting to his work. Even though he has established an impressive client list—including celebrities, products, and corporations such as American Express, Apple, Cymbalta, Hershey’s, Mercedes-Benz, Wrangler, and Nike—while attracting a following of serious collectors, the down-to-earth artist is humble and grateful regarding the success he has achieved so far while pursuing his passion.

As with most passions, Crum came upon his love of photography by instinct. A big music fan, he started out taking pictures during the live concerts he attended. Also interested in news events, Crum studied journalism at the University of Arkansas (UA). When a friend who worked at the Arkansas Democrat helped Crum, then twenty-one, land a part-time job as a photojournalist, everything suddenly clicked. From learning to write good stories, portraying situations as they unfolded through the eyes of a camera lens naturally followed. “I realized I could take pictures of the news,” says Crum. Since UA did not offer a degree in photojournalism at the time, the budding photographer’s self-taught skill evolved as he applied what he learned through his own research and refined his techniques along the way. At twenty-three, Crum took a giant leap of faith in himself when a New Orleans paper, the Times-Picayune, hired him as a staff photographer.

Captivated by individuals’ stories as reflected in their expressions, Crum is most widely known for his portrait work. “I’m after something more than physical beauty,” he says, as shown in a richly varied portfolio that evokes a bounty of emotions. Some images convey joy, others depict thought. Each is poignant and, as seen through the eyes of the photographer, beautiful. “Spiritual beauty transcends this idea of looking good,” says Crum, who adds that he can find redeeming qualities in almost anyone he photographs.

[double_column_left]

This premise of perfection can be the Achilles’ heel of photography. I like a portrait that pronounces the truth, the spirit.

His commercial assignments, therefore, attract advertisers who want natural portrayals more than glamour shots. “Airbrushed images sell products,” acknowledges Crum, who appreciates the need for retouching, especially in the fashion industry, but that area of work does not interest him. “This premise of perfection can be the Achilles’ heel of photography. I like a portrait that pronounces the truth, the spirit.”

In that vein, Crum delves beneath the surface to connect with his subjects. “I ask a lot of personal questions,” he says, considering it a gift that he relates easily to people. Beyond the pleasure of learning their stories, the photographer gains insights that enable him to expose who they are from the inside out. “The face exemplifies a person’s story and depth of emotions,” says Crum.

Not surprisingly, when it comes to photographing celebrities, Crum appeals to those who are well seasoned, such as Sean Connery, Willem Dafoe, and Sir Anthony Hopkins, because their aim does not involve producing faultless portraits of themselves. “The older guys are comfortable in their skins,” he says. “In comparison to the young stars, who are often worried about their image, the ones who have been around are more relaxed and more likely to treat people who are working on their behalf with kindness.”

Treating others with deference and working without ego is also fundamental to the collaborative environment of a commercial project, which can demand cooperation from a sizable team—ad agency personnel, stylists, makeup artists, and others. “In some ways, I have to be a field general, respecting people’s skill sets and endearing them to me so that we work well together,” says Crum, who values his responsibility to deliver results that fulfill each client’s vision on time and within budget.

Even though he contends with a number of constraints, Crum welcomes the challenges of commissioned assignments. “For an advertisement,” he says, “I work off predetermined layouts, but I’ve been hired for the job because the client wants what I offer from a stylistic perspective—the way I use lighting or how I will capture a persona on film.”

Even when much of the design is determined before he is hired, those projects ignite his creativity. “You can count on the unknown,” Crum explains. “There will always be unexpected variables—such as the weather, props, or a background—which I’ll use to my advantage. Adding and extracting various elements, I’ll build upon the idea. That’s my strength: using what is there and then, perhaps seeing a certain angle that reads better or flaring the lens with sunlight.” Knowing that the results always show his best effort, Crum relishes the rewarding pay and perks—such as traveling all over the U.S., the Caribbean, Mexico, Canada, Argentina, Europe, and Indonesia with great accommodations—that now come with the territory.

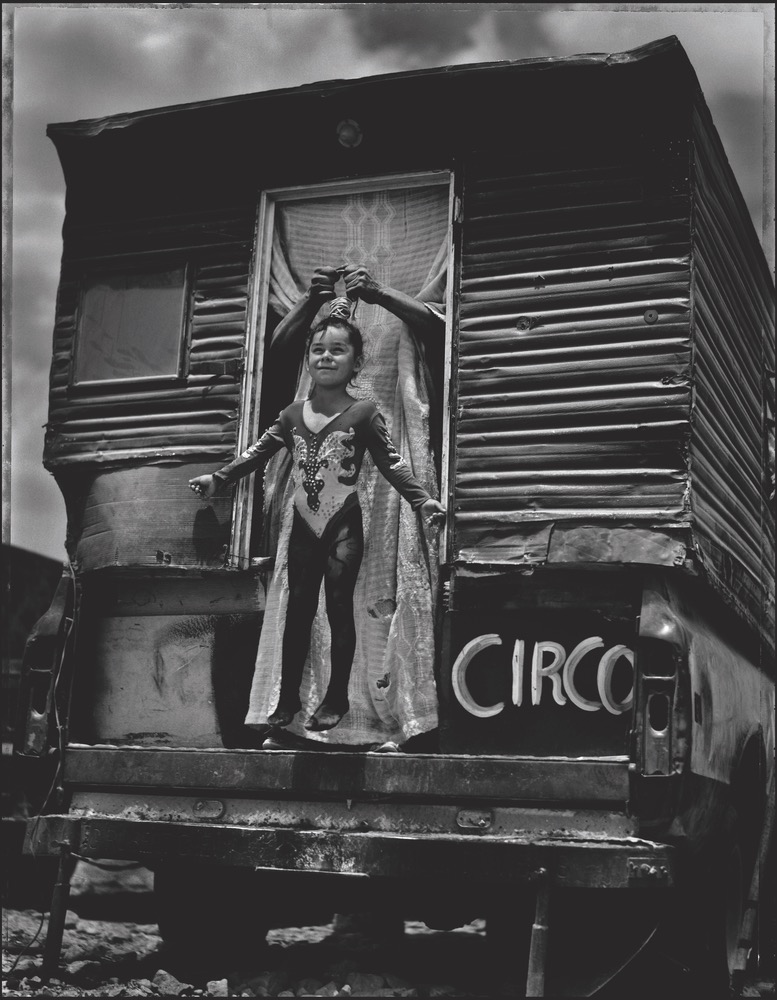

When devising his own projects, Crum is drawn to photograph the people of relatively primitive cultures. Referring to his studies of Mexican Indians, he says, “They don’t know how to pose, and they don’t spend time trying to look good.” Crum further recognizes a sense of freedom in the faces of those who live simpler lives unencumbered by materialism. “I see enlightenment,” he says.

In comparison to the young stars, who are often worried about their image, the ones who have been around are more relaxed and more likely to treat people who are working on their behalf with kindness.

One of his favorite portraits is of a group of five beekeepers from Mexico. “The women were shot in the late afternoon when there was barely enough light to make a photograph,” says Crum. “Wearing their masks, covered in dried honey, they look almost alien.” Among all of his images, Crum describes an Argentinean herdswoman as the one that most touches his soul. “She is walking up a hill with her cattle, and you see her traveling from behind,” he says. “The ethereal quality of it is moving to me.”

In general, however, Crum is not emotionally connected to his portfolio. “I feel totally detached from most of my photographs,” he says. “I’ll look at my early work, and it makes me queasy,” he says. “I can’t believe I got paid to do that!” Apparently, Crum is his toughest critic. Primarily, he is always looking ahead to the next project and striving to move forward as an artist.

In that effort, Crum’s fascination with osteology, the study of bones, becomes apparent. Describing himself as a cultural anthropologist and admirer of Charles Darwin, the photographer is a natural history enthusiast. As evidence, his studio houses an assortment of taxidermy, including skulls, as well as skull carvings by the Dayak tribe, a people who are indigenous to Borneo. “I have a mini natural history museum in here,” Crum admits as he admires his “dead friends,” who are displayed about his studio and in boxes. As part of his interest in the structure of living things, he is planning a collection that pairs pieces of taxidermy with portraits. Likewise, Crum will embark upon an ambitious project of creating collage works with skulls.

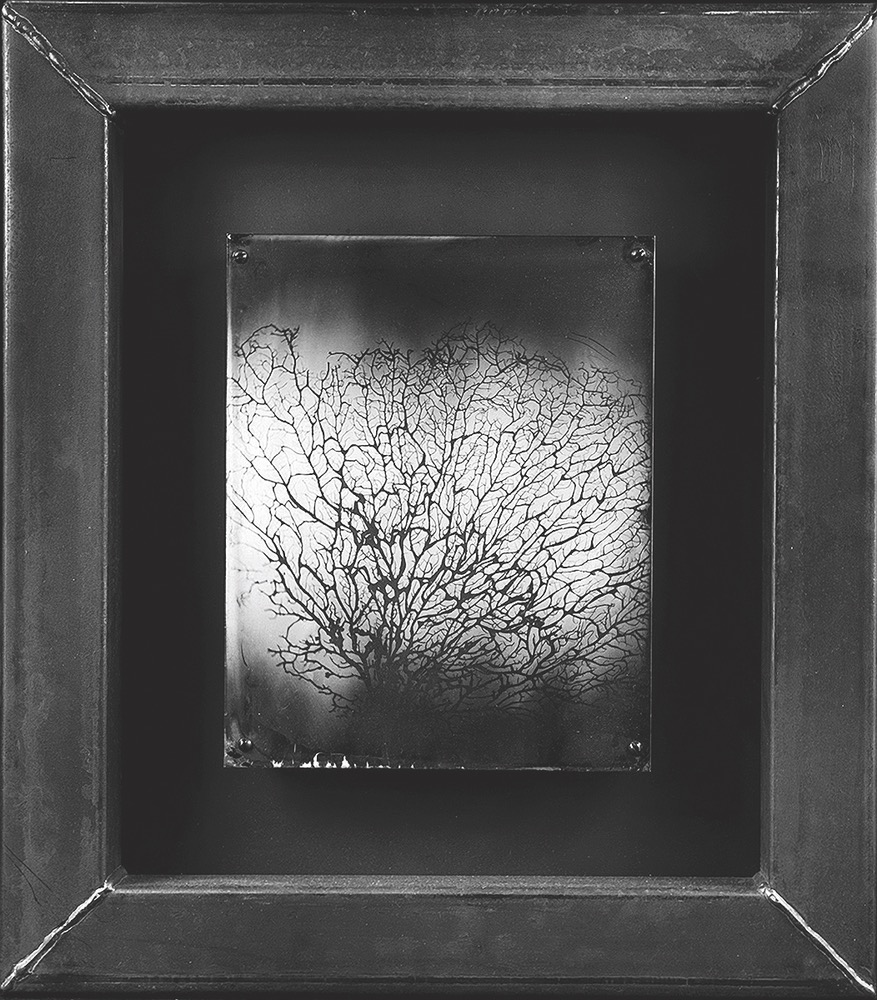

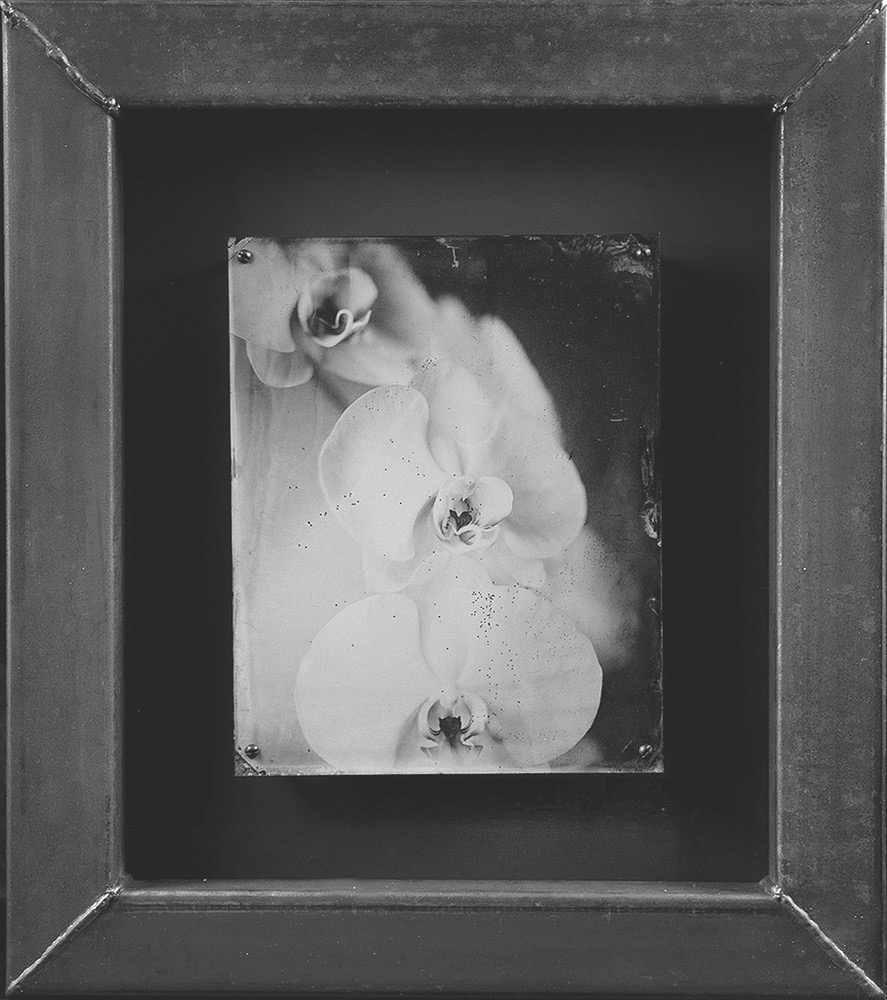

Crum is also interested in the history of photography. “When I entered the field of photography, we processed our film and printed it daily,” he says. “That now seems archaic. We no longer need darkrooms.” Nevertheless, for the hands-on creativity of the process and the final effect, he produces his own photographic plates—tintypes (on metal) and ambrotypes (on glass). A collection of flower tintypes is available for viewing on Crum’s website.

[double_column_left]

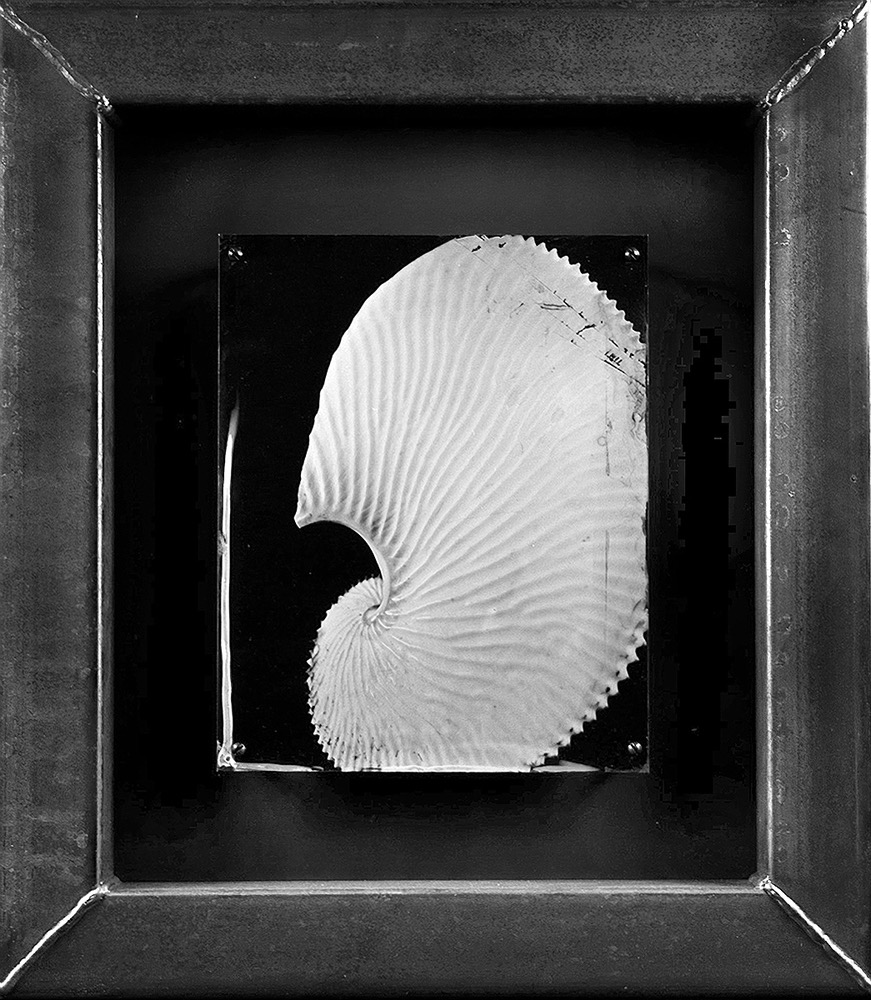

Series of still life 8” x 10” collodion process tintype plates using a 1860’s large format camera.

“Making plates is an organic process,” he continues. “I love the feeling of pouring silver on a surface. It takes me back to the craft and to a different time when making a photograph was like magic.” While he optimizes digital technology, investing heavily in the latest equipment, Crum admires the artistry of photographs produced by the old techniques. “The interesting thing about making plates is that it’s an inexact science,” he explains. “Unlike digital files, photo plates are not clean. They might be scratched or uneven in thickness, so anything can happen when you enter the darkroom.” Those so-called mistakes, Crum says, add texture and markings to the image. “The result is art.”

[/double_column_right]I love the feeling of pouring silver on a surface. It takes me back to the craft and to a different time when making a photograph was like magic.

From an artistic perspective, he also maintains that a certain feeling is lost when making digital pictures. “Today’s cameras are amazing with what they can capture, and you can shoot so much,” says Crum. “It’s a machine-gun effect, however, and no particular frame feels quite so special in the taking.”

Still, no matter what kind of camera he’s using, Crum easily gets lost in what he describes as an “alter world” of looking through a lens. “The camera lens shows me everything in reverse,” he says, “but I’ve become sensitive to shape, form, and motion through intuition. I’ve learned to build upon what I feel.” At certain points in time, then, his artistic instinct reveals that what he’s seeing is powerful. “That experience is transcendental to me,” says Crum, who lives for those “white light” moments.

Striving for ultimate satisfaction in his work, Crum believes he still has a long way to go in his journey. He is inspired by Robert Rauschenberg, the twentieth-century American abstract artist who defied convention by incorporating nontraditional materials, including bits of trash, to create combinations of painting and sculpture that portrayed everyday people and objects. “I aspire to be something of that ilk,” says Crum. “Just thinking about people who work at such a level of greatness is inspirational to me.”

[double_column_left]

Crum photographs on his Dayak Tribe carved boar skulls with his vintage 1860 large format camera at his studio in Santa Rosa Beach.

To some, such as photographer Jake Meyer, who took the portrait of the artist featured here, Crum is a great inspiration. A mentor to Meyer, Crum is also happy to share what he has learned as he continues his journey.

He says that he would like to travel to India. “I have a huge fascination with elephants,” says Crum. Most likely, his beloved wife and their two children, a seven-year-old daughter and two-year-old son, will accompany him on that trip. “My life has been great, but I didn’t really have anything until I had the love of my wife and children.” At the time of the interview, Crum was almost giddy, enjoying the beauty of his studio, with music playing in the background, as he prepared to photograph his children later in the day. “I’m still like a kid,” he admits.

Contemplating his good fortune, he said, “This is all I can ask for: to be busy in my studio, producing my own work that I can sell and exhibit to create a legacy. I’ll always want to find a rhythm that allows me to produce something every day, working to my last breath.”

— V —

To view Lee’s photography, please visit www.LeeCrum.com. All inquiries, please contact Cynthia Held & Associates, 742 N. Sycamore Ave, Los Angeles, Calif. 90038 – (323) 655-2979.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE