vie-magazine-wall-of-courage-hero

Through a sponsorship program of fifty dollars per month, the Tchukudu Kids Home in the Congolese town of Goma is presently supporting about 120 children.

Wall of Courage

Shining a Light on Africa’s Forgotten Children

By Tori Phelps | Photography courtesy of Heather Haynes

Canadian painter Heather Haynes needs only one word—courage—to tell the stories of millions of women and children.

The thirteen-year-old girl had walked for five days, without food or water, to reach a medical clinic in the Congo. One of her arms had been held in a fire by a band of rebels, leaving her with a charred stump. When Heather Haynes found her outside the clinic, heartbeats away from death and her rotting flesh covered in flies, she didn’t look away. For hours, Haynes patiently fed the girl small bites of food as she fanned the flies away.

Haynes wasn’t a medical professional or even a clinic volunteer. She was a painter whose eyes had been opened to the horrors taking place in the Congo—and who had refused to close them again. Of her decision to stay beside the girl, whose image will forever be etched in her mind, she simply says, “Who was I to walk away?”

The truth is that Haynes had made up her mind not to walk away years before. A life-changing trip to Africa in 2008 had spurred the Canadian to find solutions for some of its most vulnerable people. And when she and American Shay Bell joined forces in 2013, those solutions began to multiply. Through Worlds Collide Africa (Haynes’s Canadian-based branch) and One Ndoto (Bell’s U.S.-based branch), women and children who’ve survived the unthinkable are creating a better future for themselves and their communities.

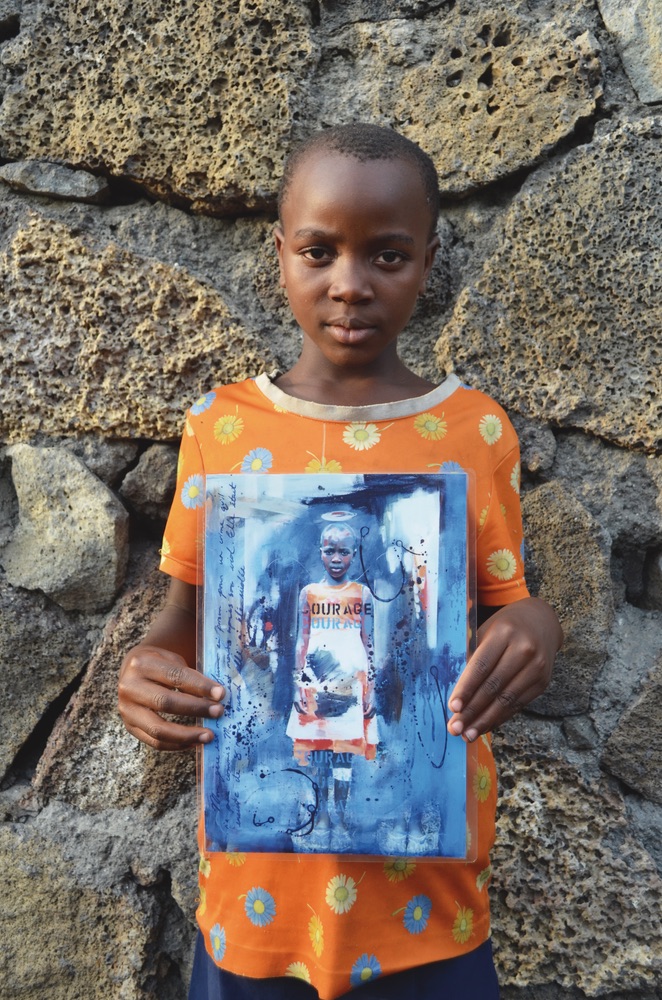

One of the ways Haynes is bringing awareness to the atrocities in the Congo is through her art. With Wall of Courage, a heart-stopping installation of eighty portraits depicting African orphans, she has put faces to the statistics while daring viewers to remain apathetic.

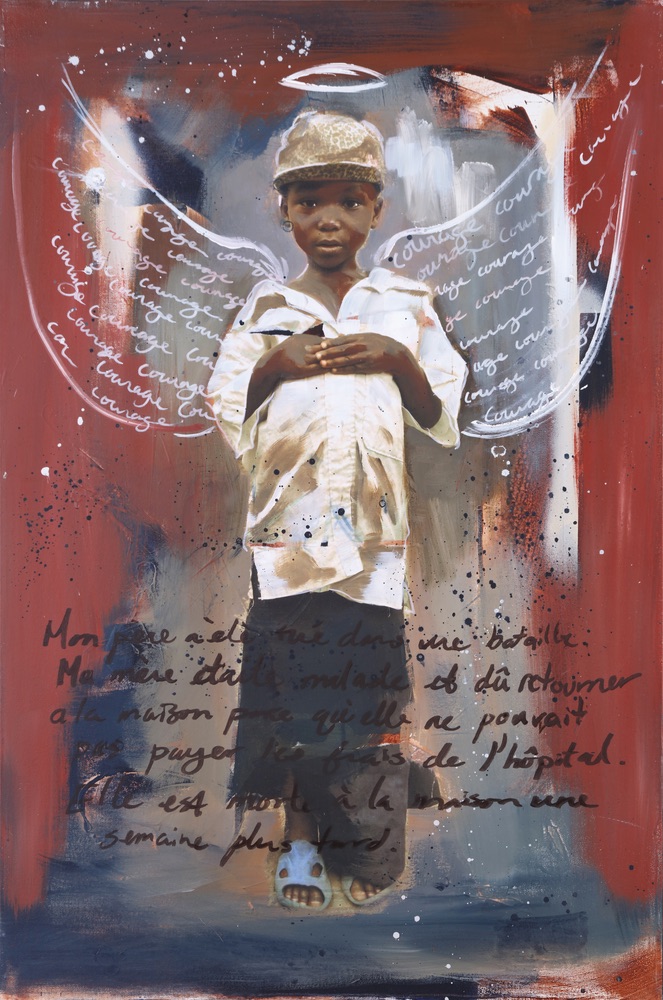

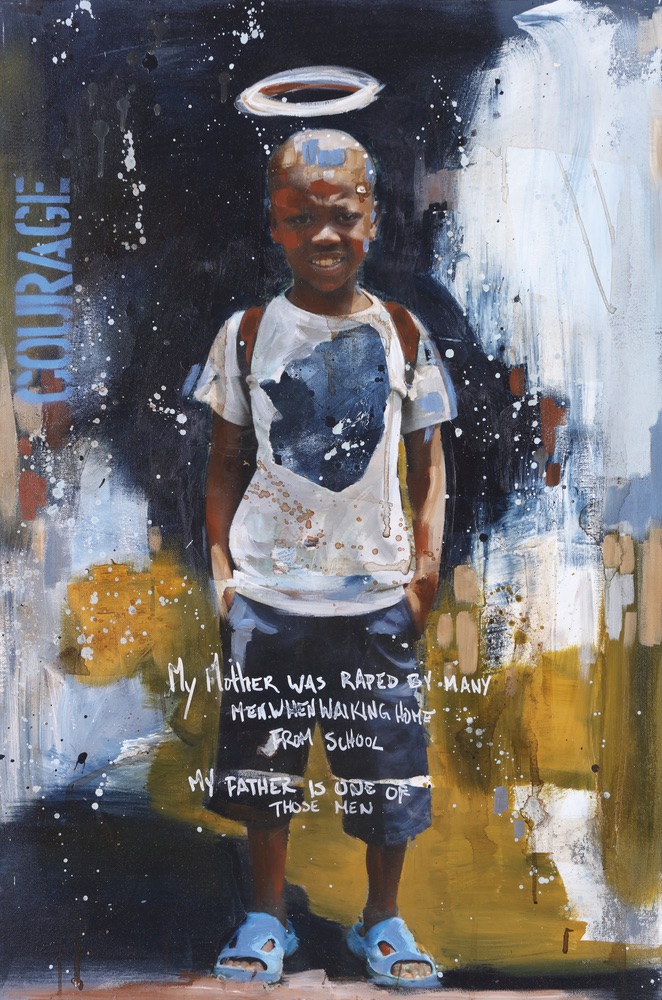

Many of Heather Haynes’s Wall of Courage paintings include tragic stories about the children depicted, some of whom have been maimed, seen their parents die, and had other horrors befall them. Still, they have not lost hope.

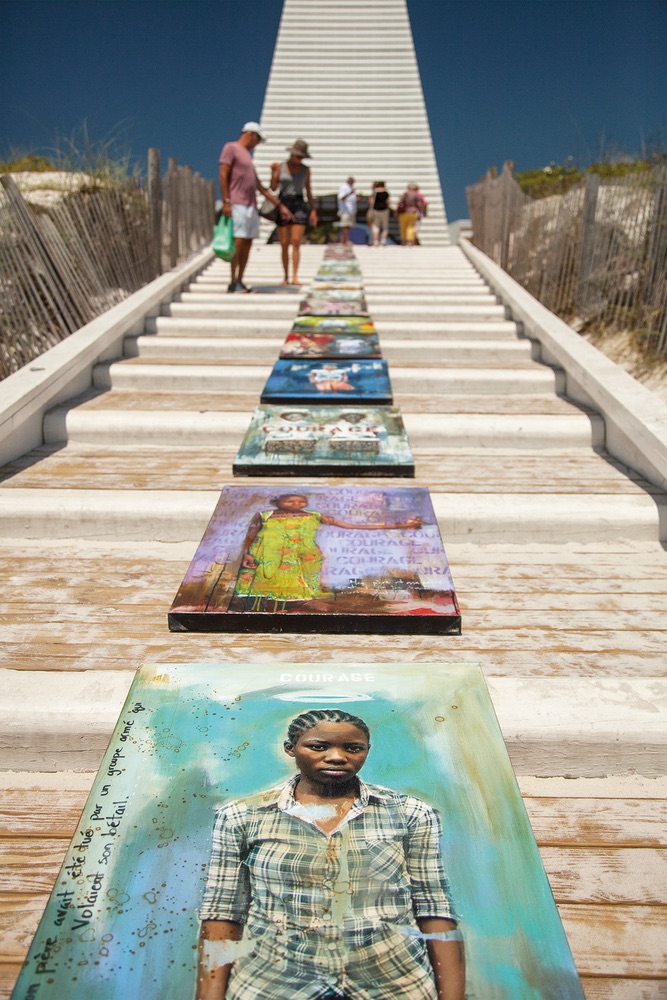

It’s safe to say that no one walked away unaffected during the installation’s month-long tenure at the Seaside Institute along Florida’s Gulf Coast. She hopes the stop is just one leg of a worldwide tour that educates and inspires audiences to adjust their mind-set. “I want people to see that we are one world,” Haynes says, “and we need a global consciousness.”

It was slipping away, Haynes knew. She had achieved the near impossible by becoming a successful painter, but just a few years after the money started rolling in, her creativity was rolling out. The Ontario native felt like she was making the same painting over and over, and she needed a big dose of inspiration stat. Based on nothing but a gut feeling, she believed she would find it in Africa.

And she did.

Uganda was a master class in authentic living, and the trip showed her exactly what had been missing in her life and work. “The connection the African people allow with others just captivated me,” Haynes confesses. “In Western culture, we’re not comfortable with it. They have such open hearts and are a very present people. It brings out the reflection in you, and I was able to realign myself.”

After the visit, she was on fire artistically. She knew she had to make room for what she had discovered, so Haynes and her husband sold their home to allow her to paint what she wanted—rather than what sold. They traveled the world with their two boys for a year and then moved the family into a small cabin.

Her next trip to Africa took Haynes to Tanzania and the Congo, where she met two women who shared stories of surviving the brutal rapes that are almost systemic in the Congo. Haynes’s heart broke for the women and for the millions who had found themselves in this unwelcome sisterhood. She turned to her paintbrush, as she always did when her emotions overflowed, and discovered that the women’s portraits not only captivated audiences back home, but started conversations about a vicious epidemic.

Her focus broadened after a chance meeting with a Congolese man named Kizungu Hubert. Over a casual conversation in an African café, she learned that Hubert had dedicated his life to caring for orphans. The two e-mailed frequently when Haynes returned home, and Hubert began sharing more about the sixteen orphans he’d rescued from life (and death) on the streets. Though he, too, felt great compassion for what his countrywomen were suffering, Hubert pointed out that their stories became their children’s stories. “The fallout of what was happening to the women was that millions of children no longer had homes or anyone to look after them,” Haynes explains.

Resolving to fund an orphanage for Hubert’s kids, Haynes shared the idea with family members and a few friends one day. By the end of that day, she had enough money to build an orphanage: the Tchukudu Kids Home in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo. It opened exactly one year after her initial encounter with Hubert in the café, by which time the number of kids under his care had swelled from sixteen to eighty.

Haynes didn’t stop there. She secured sponsorship for the Tchukudu orphans and partnered with similarly minded friends to empower local survivors through grassroots initiatives. Her first inclination, Haynes admits, was just to send money. But Hubert reminded her that giving a man a fish feeds him for one day, whereas teaching a man to fish feeds him for a lifetime. The answers had to create permanent change, rather than temporary relief.

- Most of the children in Haynes’s paintings had never had their pictures taken before and were excited to be part of the art project to tell their stories.

- Wall of Courage paintings were displayed and photographed around Seaside to raise awareness for the installation at the Seaside Institute.

- Patrons are able to purchase a Wall of Courage painting, which will continue to tour and inspire viewers as part of the full installation before being bestowed upon its new owner.

During a trip to the orphanage with her friend, Cathy Cleary, ten local women poured out their stories to the two visitors. Even after years of being intimately involved in the realities of the Congo, Haynes wasn’t prepared for what she heard. “These women—the only thing they had left was their stories,” Haynes says. “We asked them what they wanted, and they all said ‘peace.’ They didn’t say a new house or money. Just peace. It was really powerful.”

“These women—the only thing they had left was their stories. We asked them what they wanted, and they all said ‘peace.’”

Out of that meeting evolved Tchukudu Women’s Training Center, a place where women learn new skills to support themselves and their children. Many women in Goma had lived as rural farmers all their lives, Haynes explains, but when they were forced to flee their villages for the city, they no longer had a way to feed their families. The only option was to become a coal carrier—essentially a human mule loaded down with tremendously heavy bags of coal, forced to walk many miles every day to earn just one dollar.

The Tchukudu Women’s Training Center, however, offers them a chance to reclaim their lives. Once primarily dedicated to skills such as sewing and weaving, the Center has expanded its activities to avoid flooding the market. One recent idea: using the endless supply of lava in Goma to make trendy lava jewelry. A company that specializes in essential oils, doTERRA, is even evaluating the feasibility of partnering with the Center to make lava oil diffusers.

If the women and children Haynes met stimulated her altruistic side, they also spurred her creative side. Early on, her mind was filled with the faces of the original sixteen orphans, and Haynes knew she wanted to capture them on canvas. As she was painting, she was consumed with thoughts of what it would feel like to be these children or their mothers. “All of a sudden, the word ‘courage’ was in all the paintings,” she says. “I don’t even know how it happened, but it was a great big wall of courage in my mind.”

Soon, it was a wall in real life, too.

Shay Bell and Kizungu Hubert

When fifteen of the paintings had been completed, she laid the canvases in a grid and stood back. At that moment, she realized it was one big painting and that she had to paint all eighty children. The past twenty years of her career swirled together in a single vision, overwhelming Haynes with the intensity of it, but also giving her clarity and energy she’d never experienced.

“All of a sudden, the word ‘courage’ was in all the paintings. I don’t even know how it happened, but it was a great big wall of courage in my mind.”

Wall of Courage, as it was officially dubbed upon completion last year, covers 480 square feet. Breathtaking in its scope and visual impact, the Wall is a powerful tool in highlighting a crisis that’s being largely ignored by the Western world. And when Haynes’s partner, Shay Bell, and Dr. Heather Glenn—both longtime Emerald Coast residents—heard about the Wall, they knew it had to come to Seaside.

What compels a person to give up everything they love, move halfway around the world, and embrace regular heartbreak? For Bell, it was kids like the ones on Haynes’s Wall of Courage.

Familiar to many as an executive at the iconic WaterColor Inn and Resort, Bell had it all: a lucrative career, a loving fiancé—“a beautiful life,” she admits. When the resort closed briefly for renovations in January 2011, she used the downtime to teach English in Tanzania. She’d been to Africa once before and had enjoyed it, but this time was different. She returned a woman on a mission, founding One Ndoto (“one dream”) from Florida but soon realizing she needed to be in Tanzania full-time. That meant resigning her position, selling everything she could, and splitting with her fiancé (who, happily, remains a good friend).

In Tanzania, Bell connected with a group of former street kids who were investing in their community through their own art, as well as providing free art lessons. Haynes was one of the group mentors, and soon the two women were friends as well as partners in their nongovernmental agencies, Worlds Collide Africa and One Ndoto.

In 2013, Bell helped launch the Pamoja Tunaweza Boys and Girls Club, whose purpose is to empower “street kids” to reach their full potential and become positive members of society. It’s easier said than done. In Tanzania, the stigma of being a street kid is often enough to derail that child for life.

From the beginning, Bell recognized that her role wouldn’t be—couldn’t be—boss. “As a white woman from America who’s been relatively privileged her whole life, I can’t relate to a kid who’s been on the streets since he was five,” she says. “I don’t pretend to. I’m just a conduit.”

Instead, the leaders of the organization, former street kids themselves, make all the decisions. Bell’s task is to help guide them toward growth and ensure complete financial transparency. Perhaps most importantly, she showers the kids with unconditional love—something of which they have precious little experience.

Transforming lives takes money, though, which is why Bell is always assessing new ways to support the kids. Recently, she harnessed knowledge from her previous life to create the Worlds Collide Africa House, an upscale guesthouse and home base for tourists on safari, Kilimanjaro climbs, or art and yoga retreats. As a high-end hospitality industry veteran, she saw potential in an abandoned building and guided its transformation into a fourteen-bedroom residence that has become a job source for locals, as well as a revenue stream for One Ndoto/Worlds Collide Africa projects.

The former atheist-turned-believer sees a heavenly hand at work in everything that’s going right for One Ndoto/Worlds Collide Africa. And she sees a staggering depth of faith in the people for whom things have gone very wrong—like the woman whose husband and eight children were slaughtered by a rebel group in the middle of the night. She had escaped the same fate only because she was using the latrine behind their mud hut. “She looked at me and said, ‘I don’t want to live, but I know that’s not God’s plan for me,” Bell shares.

Bell has learned to be resilient; it’s a necessity when the day might bring the death of a child or a survivor’s gut-wrenching tale. But “resilient” doesn’t mean “unaffected.” She marvels that, as different as the individual stories are, they’re consistent in their horror. And no one seems to be paying attention. “This is happening today,” she says. “The fact that it’s not out there—that people aren’t outraged—is stunning to me.”

Bell has learned to be resilient; it’s a necessity when the day might bring the death of a child or a survivor’s gut-wrenching tale. But “resilient” doesn’t mean “unaffected.”

A twenty-year war in the Congo has taken six million lives and left untold millions of others plagued by memories of unspeakable tragedy. Many of the survivors are children, like the ones at Tchukudu Kids Home. And when Bell learned that Haynes had completed her Wall of Courage featuring some of “their” kids, she knew it was meant to be exhibited back home in Florida. Thankfully, her friend Hillary Glenn stepped in.

Shay Bell, Heather Haynes, Hillary Glenn, Jennifer Kuntz, and Anne Hunter in Seaside, Florida

Sitting on the balcony of the Worlds Collide Africa House and surveying the beauty of the Tanzanian landscape, Glenn came to an easy decision: she would help bring Haynes’s Wall of Courage to her privileged pocket of Florida. Back home she was a nurse practitioner at a Miramar Beach urgent care center. Today, however, Glenn was in Tanzania for a charity climb of Mount Kilimanjaro to benefit Bell’s One Ndoto.

She had been friendly with Bell on the Gulf Coast, but it wasn’t until her trip to Africa that she understood the purpose of Bell’s new life. “Shay looks at these children—young adults, really—and treats them as if they were her family,” Glenn says. “She’s not tossing aid at them. She’s giving them life skills and tools and really caring for them.”

It took zero convincing for Glenn to pledge her support, and she began her hunt for exhibit space as soon as her plane touched down in Florida. When she approached Seaside gallery owner Anne Hunter about hosting Wall of Courage, Hunter agreed, not only signing on as a partner but also developing an artist-in-residence program for Haynes’s visit. Anne Hunter Galleries then joined forces with the Seaside Institute to serve as the venue for the installation.

The steady stream of visitors, many referred by others who’d experienced the Wall’s unique power, created a buzz throughout the Emerald Coast last April that still hasn’t died down. People approach Glenn daily to discuss its impact, and that response, she says, has made her fall more deeply in love with her community.

Glenn was especially gratified to see young visitors’ kinship with their African peers, reacting with love rather than fear. She credits Haynes’s masterful ability to capture a lightness about the children while not shying away from the weighty subject matter. “Putting ‘courage’ on the paintings makes you really see them—not pity them,” Glenn enthuses. “You see the joy behind the child.”

Bell, who says she’s not a crier, admits she was brought to tears frequently during the installation. Even though her life and work have taken her across the globe, she still sees the residents of 30A as extended family members. Their support—and the number of people who now want to be part of this story—mean a great deal to her.

Some of that support came in the form of generating solutions that would allow Wall of Courage to continue its international tour. Haynes was particularly intrigued by the idea of attracting a sponsor for each painting who would take possession at the tour’s conclusion. Her hope is that the investors’ altruistic act will pay feel-good dividends as well as real dividends in the form of an asset whose value would increase substantially over the years.

The Tchukudu Women’s Training Center teaches sewing and basket weaving to Congolese women who find strength in each other and in telling their stories.

The tour is important to Haynes—not to gratify her own ego, but to shine a light on the Congolese devastation and pay tribute to the children who make up the Wall. “At one point, those children were alone,” she says. “Now, in a sense, they’re traveling the world. And all these people are behind them, putting energy into who they are.”

Energy is being directed toward other Worlds Collide Africa/One Ndoto projects as well. Glenn, for one, wants to expand the Kilimanjaro climb for One Ndoto and volunteer in the clinic they’re planning for the Congo. The future medical clinic on Idjwi Island, currently under construction on donated land, is intended to prevent maternal and infant death during childbirth—an all-too-common outcome that adds to the area’s man-made misery.

Whether it’s the clinic, the Agricultural Project (which produces fresh food for the Tchukudu Kids), or the Boys and Girls Club, the underlying goal is the same: self-sustenance and self-determination. Worlds Collide Africa/One Ndoto is making progress, Haynes says, because it equips locals to make decisions, rather than trying to force Western “solutions” on them.

“It starts with being aware of what’s going on and then stepping out of your comfort zone. That’s what binds Heather and me together; once we became aware, we became a voice for people without.”

In the same way, Haynes and Bell don’t force anything on potential supporters. Instead, they connect the dots between those who need help and those with something positive to offer. No need to sell everything and move to Africa, Bell promises. “It starts with being aware of what’s going on and then stepping out of your comfort zone,” she says. “That’s what binds Heather and me together; once we became aware, we became a voice for people without. Find your part within the story, even if that’s going to work and talking about it.”

If you’d rather write a check than discuss such an unpleasant topic, you’re not alone. And that’s why Wall of Courage is so important. Far more than just brilliant art, it’s a potent reminder of the consequences of turning a blind eye to injustice “over there” and an opportunity to feel connected to something bigger.

It’s an experience Haynes wishes for everyone. “What I find is that Africa reconnects you with your truth—who you really are,” she says. “It gave me the strength to witness when other people turned away. I feel it’s part of my calling to be that witness and then tell those stories through art.”

— V —

Visit HeatherHaynes.com, WorldsCollideAfrica.com, and OneNdoto.com to learn more.

Tori Phelps has been a writer and editor for nearly twenty years. A publishing industry veteran and longtime VIE collaborator, Phelps lives with three kids, two cats, and one husband in Charleston, South Carolina.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE