VIE_Suzanne_Pollak_HERO_OCT21

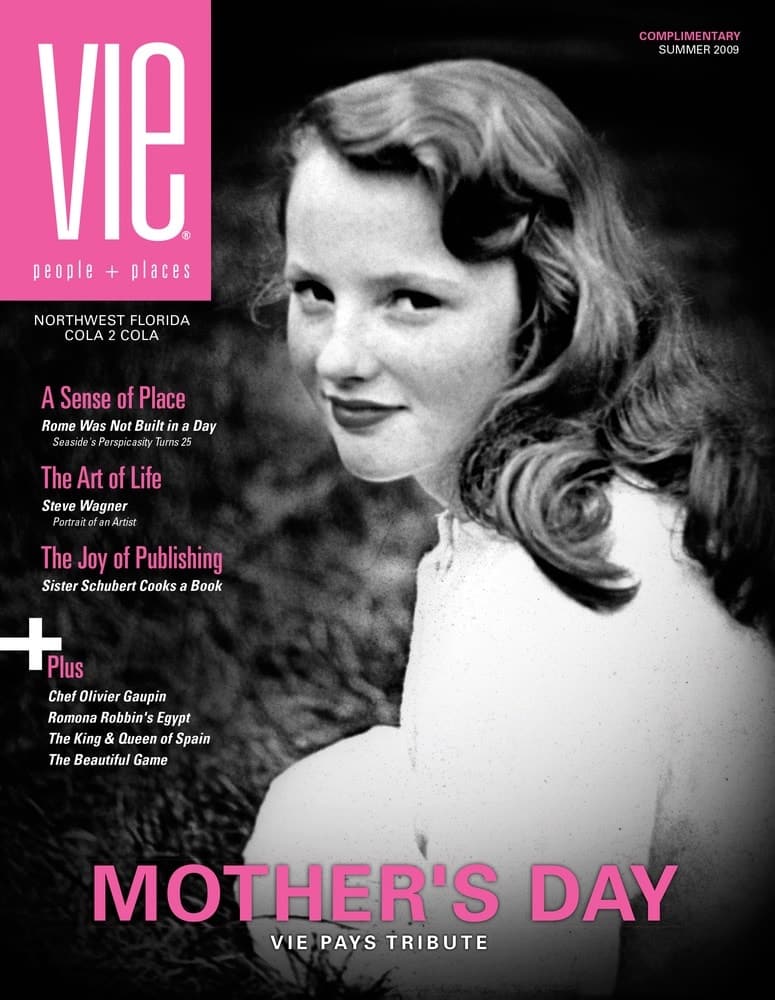

Traveling Through Memories

By Suzanne Pollak

I write about my life in Africa because my father didn’t write about his. The day he spent telling me stories, ranging from receiving his last rites at twenty-two to being the last American in eastern Nigeria during the Biafran War, I saw a movie in my mind. I wondered why he’d never shared any of this with me before. He was dying of cancer, and we spent a day traveling through South Carolina from Hilton Head to Charleston, then to Savannah, Georgia, and back again to Hilton Head. In the seven hours that I drove, he talked. I knew I should take notes, or better yet, record him, but all I could do was listen.

He told me about safaris from another era, long before big game animals in Africa were becoming extinct. He shot a charging elephant, gazelles, ostriches, and the most dangerous animal of all, a Cape buffalo. Nothing went to waste. We ate the gazelle meat, my mother had an ostrich purse made, and the Africans used every part of the rest of the animals.

My father earned a reputation as the Great White Hunter. This legend was born the day he accidentally shot two gazelles through the lungs with one bullet. The fact that the animals were lined up one behind the other didn’t matter to the Somalian hunting guides. They were convinced that my father was a god, a man who divined what was happening and how to handle it. He told them it was an accident, that he didn’t know there were two gazelles. But from that moment on, he was invited to the opulent safaris usually booked exclusively by wealthy Europeans. In addition to hunting the exotic (not yet endangered) African animals, it was a week living like no other: sleeping tents, eating tents, and multicourse dinners; cigar smoking and cognac drinking in the African bush; an atmosphere of gorgeous, seductive, often menacing wildlife, including a charging elephant ready to run over the only tree separating him from my father.

Later on, he described his time at the University of Chicago, listening to Louis Armstrong play the trumpet at nightclubs and learning from Enrico Fermi, the physicist known for developing the first nuclear reactor. My father tried to get me interested in quantum theory and nuclear physics by giving me Scientific American magazines during my youth. I was more concerned with making a friend before we moved again. After Chicago, he attended Columbia and drove an MG packed with two tuxedos (in case one of his friends forgot theirs). He lived in Greenwich Village with his vast record collection—a library that grew substantially throughout his life. It became large enough to cover several walls from floor to ceiling in our African houses.

That’s when I learned about western music—at the age of nine in the off-beat Nigerian city of Enugu. I listened to music with my father at night after dinner, and later on, we listened to the opera every Saturday in Liberia. Knowing he was dying of cancer at age sixty, he tried to make me feel better by saying he’d lived on borrowed time since he fell mysteriously ill at age twenty-two. He was sick enough that his parents traveled from Connecticut to Fort Benning, Georgia, and he received his last rites there while he was a Green Beret and an Army Ranger.

He shared aspects of CIA life: how spies recruit agents and deliver secrets and what happens when you have a dozen names. I learned the depth of my father’s love for Beethoven’s late quartets, his secrets for hosting the most sought-after parties, and his wiring abilities honed at the American Embassy offices so his cohorts could listen to his music. Unfortunately, he died a few weeks after our drive before I could put any of his stories to paper in his words.

My memories are different from his because I was a child in Africa.

I wish my father had written his stories down because his life was from another era, shared by few others. I write about mine because I want my grandchildren to know about my girlhood that is so different from their upbringing.

A strange part of my African life was returning to the United States every two years for vaccinations and my father’s new posting. Africa was not a foreign continent to me; it was the only normal part of life within my crazy family. In Africa, I felt free, accepted, and stable. In America, I found the streets too wide. Instead of flame trees stretched across dirt roads, billboards crowded the sides of highways. I found the grocery stores weird. How many choices of dry cereal does a human need? I wondered at the time. And without our staff to play with, I had to be more dependent on my unstable mother. I had no idea how to connect to American children my age. When they asked me if I chased lions away from our house, I wanted to cry. I felt separate and estranged in this country.

We never visited America long enough for me to get a better understanding of life there. My ideas exploded when I left Liberia to attend St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire. Before the term was ever used in this country, I considered myself African American. But when I said hello to the Black students at St. Paul’s, I couldn’t seem to make a connection. They hardly ever said hello back to me and gave me strange looks when I sat down beside them in the school cafeteria. It took me two decades to get used to America.

Diplomats are sent overseas to places so different and difficult that some countries are labeled “hardship” assignments. Languages, customs, manners, the role of women, the style of dress—every prior view requires an adjustment. Growing up in many of these countries, the customs and people were familiar to me, and I also realized that humans everywhere have the same needs, desires, and concerns. At thirteen, my Chinese friend and I couldn’t speak one another’s languages, yet we played tennis every week and could understand each other well. When she spoke and her mother translated her Chinese sentences, I usually guessed what she’d said.

My life in Africa was a long time ago, and large chunks of my memory lay dormant. When my eldest granddaughter, Anna, was born, some memories began to return. When I cared for her, I saw flashes from my life when I was her age. Sometimes I thought these memories could not be real, but they came, some strange and unsettling, and pieces of my past returned. When Anna turned four, I wanted to tell her my stories. She brought back my girlhood feelings.

I was born in Beirut, the Paris of the Middle East. Naturally, I don’t remember Beirut or anything about Libya either. I cannot recall Tripoli or Benghazi where I lived when I was two and three, respectively. My memory starts in Somalia. When Anna tells me her favorite color is pink and she wishes her house was painted pink, I know exactly what she means.

I lived in a pink house—pale pink surrounded by a walled garden covered with bougainvillea vines. The house sat on top of the highest hill in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. I don’t remember the Paris of the Middle East, but Mogadishu was Paris to me. The whole city lay below our house, and I could stand outside the gate and watch everything. Camels walked through the streets. The world’s most beautiful women balanced pots on their heads and babies on their backs, and the Indian Ocean shimmered in the distance.

I am beginning to understand the important role of grandparents. We can report on another era, and our grandchildren think it’s fascinating. They may be the ones to travel through our memories and record our stories for us.

Anna is the eldest of my eight grandchildren and she is still curious about my childhood. I am beginning to understand the important role of grandparents. We can report on another era, and our grandchildren think it’s fascinating. They may be the ones to travel through our memories and record our stories for us.

— V —

Suzanne Pollak, a mentor and lecturer in the fields of home, hearth, and hospitality, is the founder and dean of the Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits. She is the coauthor of Entertaining for Dummies, The Pat Conroy Cookbook, and The Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits: A Handbook of Etiquette with Recipes. Born into a diplomatic family, Pollak was raised in Africa, where her parents hosted multiple parties every week. Her South Carolina homes have been featured in the Wall Street Journal Mansion section and Town & Country magazine. Visit CharlestonAcademy.com or contact her at Suzanne@CharlestonAcademy.com to learn more.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE