vie-magazine-house-of-worth-couture-hero-min

Evening dress in satin brocade with appliquéd velvet stars; asymmetric bodice with bias panels decorated with lace, silver-thread embroidery, and brilliants; and mock tie at waist with beaded tassels, ca. 1905. Museum of the City of New York (44.158.1) Photo © 2011 David Arky

The House of Worth and the Birth of Haute Couture

By Anthea Gerrie | Photography courtesy of House of Worth

It’s a fashionista’s fairy tale: the poor boy with just a few dollars in his pocket put to work at eleven, who began designing frocks for the Parisian royal court within years of arriving in the city. Charles Frederick Worth, the unlikely, British-born father of haute couture, went on to dress the world’s fashion-conscious queens and dozens of American socialites—but the story of the House of Worth has a dark side. It’s still a mystery why his great-grandson, the last of four generations of legendary designers, abruptly quit, and what became of the fortune that should have been left as a legacy for his descendants.

“There were dresses and perfume bottles, yes—but I had to buy the ones I have collected,” says Chantal Trubert-Tollu, the designer’s great-great-granddaughter, with a wry shrug as we sip cafés noisettes in Paris’s Café de la Paix. It’s just steps from the Worth showroom that was the talk of le Tout-Paris from 1858 until 1935 when it moved to the city’s new couture hub, the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

The legacy should have been glorious, but there are no riches for the descendants, only memories—and fabulous gowns in the world’s great fashion museums as a testament to their ancestors’ legendary talents. “We don’t understand why we were left with nothing apart from some old photographs,” says Chantal, with just a tinge of well-disguised tristesse. “My grandmother was dressed by Worth, of course, and my mother got married in a Worth wedding dress, but it was wartime, and there were shortages, and she had to give it back.

“In my case, all I inherited was 6.65 percent of English blood!”

The “Spirit of Electricity” costume made by Worth for Alice Vanderbilt, 1883. It comprises a dress of seventeenth-century inspiration in midnight-blue velvet, overlaid with white satin on the bodice and gold satin on the skirt, embroidered with sequins, beads, and crystals. Museum of the City of New York (51.284.3a-h) Photo © 2011 David Arky

She now has something concrete to leave as her own legacy as the coauthor of a sizeable tome about the House of Worth, with the emphasis on the word House. “My main motivation for the book was to pay homage to the subsequent generations whose talent kept Worth at the top,” Chantel explains. “You only ever hear about Charles Frederick, when those who study fashion know his sons and their sons made their own unique contributions to keeping the company at the top.

“Why did that not continue? You’re not the first one to ask why Roger Worth left the business and what happened to everything after it was sold,” she says of his unexplained departure in 1950.

Chantal, who has devoted her career to the associated field of perfume marketing, emphasizes how unconventional making bespoke outfits was considered in 1845 when Charles Worth set foot in a post-revolutionary France where the notion of fashion itself had become politically incorrect. As she and her fashion historian coauthors explain in The House of Worth: The Birth of Haute Couture, “The French royal family had shunned imperial splendor in favor of a solidly bourgeois approach. Fashion, or rather, silhouettes, changed only once a decade, the fabrics available to buy were devoid of imagination or flair, the cuts of different dresses were frequently indistinguishable from one another, and garments were hastily thrown together by seamstresses with little finesse or embellishment.

“It was a cutthroat market in which dressmakers scraped a pittance and were not expected to be creative.”

- Afternoon dress in satin brocaded with rose motifs, open skirt front over a panel of coral-colored satin, ca. 1883–84. Museum of the City of New York (31.3.5a-b) Photo © 2011 David Arky

- Formal dress made from two asymmetric tunics in chiffon, both longer at the back, with clover-leaf motifs embroidered in glass beads, covering a narrow silk satin underdress with a train of pointed streamers, gold lamé bodice, and belt, ca. 1910–13. Private collection

Worth, who arrived in London at age twelve from the English provinces and developed an astute eye for how to best accessorize the Parisian ready-to-wear he was employed to unpack at the famous Mayfair department store Swan & Edgar, changed all that in 1853, seven years after he managed to get himself to Paris. He started making one-offs for discerning clients, launched his own house five years later, and made his name dressing the newly reestablished Parisian court, including Empress Eugénie herself. World royalty followed, including Queen Victoria, who, to have a Worth gown of her own, broke the protocol that demanded the palace commission only British firms. “Most of the orders for the coronation of Edward VII in 1901 went to Worth,” notes the book. It also lists the Romanovs of Russia, the queens of Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, and Belgium, Britain’s own Queen Alexandra (who came to the rue de la Paix for a fitting), and even the Empress of Japan as clients.

By this time, Charles Frederick’s younger son, Jean-Philippe, was in charge of design, his father having retired in the 1890s. Jean-Philippe’s alliance with Cartier, whose jewels he stitched directly onto clothes—a forerunner of the embellished sweaters of today—became one of the House of Worth’s most important innovations. The two houses were intertwined by marriage as well as business, and Jean-Philippe also pioneered the stitching of Swarovski crystals into designer gowns.

Both Charles Frederick and Jean-Philippe assiduously pursued American patronage, which kept the House of Worth supplied with funds through bad times as well as good. “Worth loved American clients because they paid, and paid right away, not like the French,” says Chantal succinctly. Not to mention the fact they spoke English, Worth’s native language, and were happy to accept his design ideas without demurral. “They accepted his approach of ‘I, not you, am going to decide what to make for you.’”

Worth was not the only house to die after Dior came on the scene, but its death was certainly accelerated by the lack of a successor.

One of Worth’s earliest transatlantic clients was Lillie Greenough, a singer from Cambridge, Massachusetts, who married Paris-based American banker Charles Moulton. But it was Worth’s flair for the theatrical that brought him to the attention of American society on US turf via his creation for the W. K. Vanderbilt costume ball in 1883. He dressed Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II as “the Spirit of Electricity” in gold satin richly embroidered with metallic filaments and overlaying midnight-blue velvet; she brandished a torch powered by batteries concealed beneath her dress. It did the trick of getting the Vanderbilts, hitherto not accepted by American high society, onto the famous Astor Four Hundred list.

Charles Frederick’s lickety-split approach appealed to the fast-moving, forward-looking Americans of the late nineteenth century; he took only twelve days to make Lillie Moulton eighteen couture outfits for a week’s stay at Napoleon III’s country palace. “He was a tyrant—he didn’t stop,” says Chantal of a production-line approach that saw bodices made in one workshop and skirts in another, presaging the eventual move of couturiers into ready-to-wear designing. He also spread the word about his designs abroad by selling his patterns.

By the time Jean-Philippe took the design helm at the turn of the twentieth century, transatlantic crossings were all the rage for the wealthy, who would come to Worth with letters of introduction and spend tens of thousands of francs. He was still dressing Vanderbilts—now Consuelo, who had married into British aristocracy as the Duchess of Marlborough. He even designed a uniform for the American society women who volunteered to work for the YMCA during the First World War. By that time, US buyers who came to Paris with commissions from private clients, as well as high-end department stores, were so crucial to Worth that the company issued them loyalty cards! One society commentator explained tartly in 1928, “Old Europe still has a few princesses able to go to Paris to dress themselves. But America now fills rue de la Paix, place Vendôme, the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, and the Champs-Élysées with corned beef archduchesses, rubber queens, and oil empresses.”

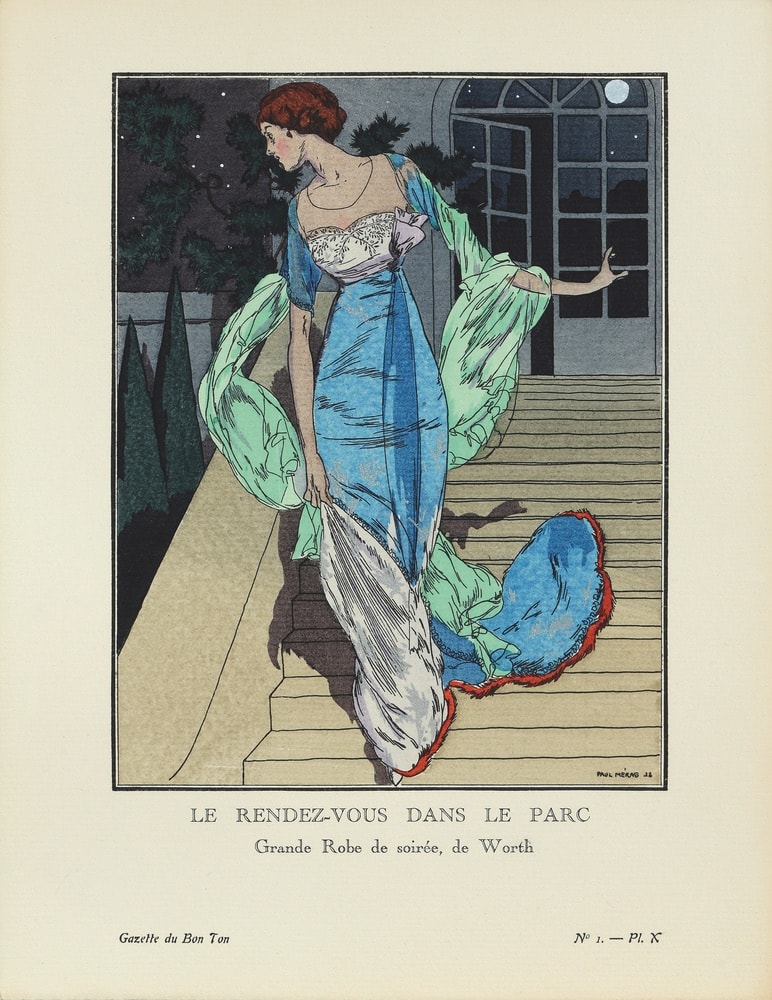

- “An Evening Gown from Worth” by A. Sandoz from Harper’s Bazar, January 20, 1894. Private collection

The shockingly fast decline of a brand that passed out of family hands in 1954 had started more than two decades earlier but was accelerated when war put a strict quota on silk and other luxury fabrics. Then Roger quit, despite having been the president of the couture manufacturers’ federation for six years. Chantal thinks the advent of Christian Dior and other post-war new wave designers marked the end of the era for the founding fathers of bespoke fashion. “Worth was not the only house to die after Dior came on the scene, but its death was certainly accelerated by the lack of a successor,” she says.

At least the influence of the father of haute couture and his successors never died; twenty-first-century designers from John Galliano to Alexander McQueen, Jean-Paul Gaultier to Vivienne Westwood have taken inspiration from Worth with shapes and materials. Christian Lacroix even wrote the foreword to The House of Worth. “His designs were so far from what others were doing; Charles Frederick would have been proud to have been an inspiration,” says Chantal.

The name of Worth also lives on through Je Reviens, the most successful of all the Worth perfumes, the first of which was launched in 1924. The name means “I shall return,” and the skyscrapers of Manhattan inspired the 1932 bottle. Charles would have been moved by the fact that his great-great-granddaughter, who gave up her career in perfume marketing to research the book, believes it will pay homage to the innovator who has inspired today’s designers to be brave and go for it.

— V —

The House of Worth: The Birth of Haute Couture by Chantal Trubert-Tollu with Françoise Tétart-Vittu, Jean-Marie Martin-Hattemberg, and Fabrice Olivieri is published by Thames & Hudson. It is available for purchase through most major booksellers.

Anthea Gerrie is based in the UK but travels the world in search of stories. Her special interests are architecture and design, culture, food, and drink, as well as the best places to visit in the world’s great playgrounds. She is a regular contributor to the Daily Mail, the Independent, and Blueprint.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE