vie-magazine-blue-ridge

Shaconage: The Blue Ridge Mountains

Story and Photography by Colleen Hinely

The Blue Ridge Mountains—the eastern segment of the picturesque Appalachian Mountain range. Beginning in Pennsylvania, the Blue Ridge extends through Maryland and the Virginias, southward through the Carolinas, and down to its southernmost point in northern Georgia. The hills and hollows of the range harbor a mystical and storied past. Tales of the native Cherokee Indians and European settlers unveil the turbulent and often vicious struggles to survive within this dense and rugged terrain.

Shaconage (shah-con-ah-jey), or “Land of the Blue Mist,” is the ancient name conferred on the Blue Ridge Mountains by the Cherokee Indians in honor of the atmospheric blue haze that blankets the hills and hollows of the range. Though it’s largely forgotten today, the Cherokee tribe inhabited these mountains for more than ten thousand years, living harmoniously in the fertile valleys and game-rich ranges of the mountain landscape. Within their uniquely peaceable existence, the Cherokee thrived as the most socially and culturally advanced of the American Indian tribes.

This idyllic life lasted until the early sixteenth century, when expedition teams led by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, and later Scotch-Irish defectors, moved in looking for gold. These new settlers anticipated a life of prosperity in the Blue Ridge Mountains, free from the religious and social persecutions of their former homelands. Instead, they stripped the land bare through overlogging and overhunting, causing shortages of food and precious hides.

Gold eventually was found in northern Georgia in 1828, marking the beginning of a ravenous onslaught of miners and the end of a once-glorious Cherokee Nation. The discovery prompted the removal of the Cherokee a full two years before the infamous Trail Of Tears, during which four thousand American Indians succumbed to disease, starvation, and exposure along the forced thousand-mile march to present-day Oklahoma.

Whether through their own poor decisions or a curse bestowed upon them by the banished Cherokee, new residents of this area did not enjoy the same prosperity as the natives. Their lives quickly dissolved into a grim and desperate fight for survival—a far cry from the sophisticated abundance once enjoyed by the Cherokee. Previously fertile valley farmlands became barren, forcing many families into the uncultivated, lawless, and primitive hillsides. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century mountain living was isolated, with families often living a full day’s travel from their nearest neighbors. The mountain soil, riddled with rock and impermeable clay, was unable to produce sufficient crops, leading to widespread malnourishment and even starvation. Rampant poverty soon induced depression and despair.

One outcome of this despondency was the rise of moonshining, the real history of which is nothing like the romanticized myths and silver screen characterizations.

One outcome of this despondency was the rise of moonshining, the real history of which is nothing like the romanticized myths and silver screen characterizations.

Moonshining, named for the clandestine conditions critical to the illicit production of “white lightning” whiskey, became a lucrative and tenable way of life for destitute people. Because moonshine production and distribution was illegal, producers erected primitive stills deep within the Blue Ridge Mountains to keep their precious equipment out of sight. The combination of the illegality and profitability of moonshining instigated the widespread, abominable conduct of life in the hills.

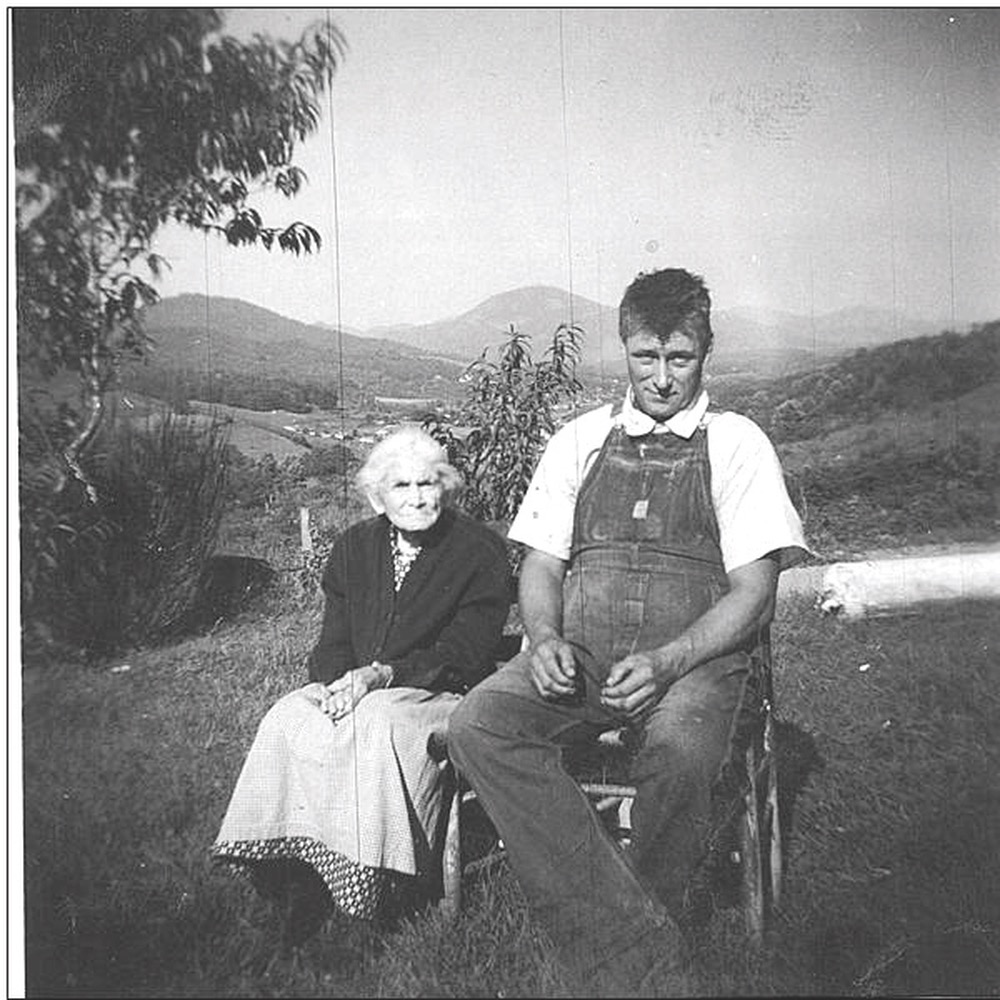

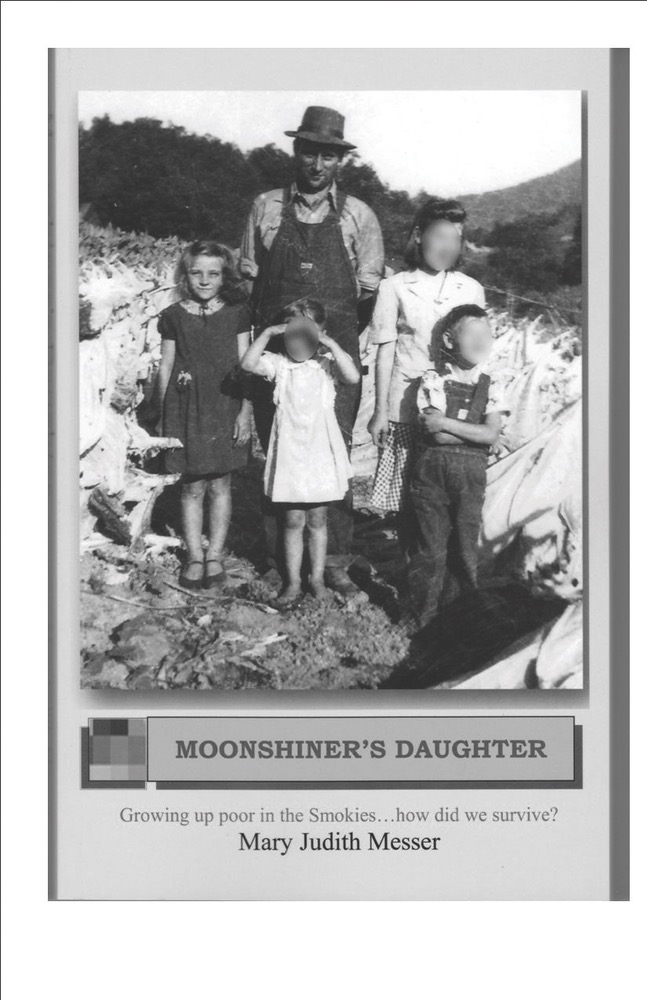

Moonshiner’s Daughter, a memoir by North Carolina native Mary Judith Messer, is a painful chronicle of the realities of the moonshine culture. In it, she details her backwoods upbringing as the daughter of a horrifically abusive moonshiner father and an emotionally inept mother. Mary’s father, Terry Lee Long (not his real name), was a revered moonshiner. He was also an alcoholic who would disappear to his remote hillside still for weeks at a time, leaving his wife and three children without money for food. The goodwill of sympathetic neighbors occasionally provided them with fresh eggs or ground corn, but the family was mostly forced to wait for Terry to emerge from the mountain depths with profits from his moonshine sales. That homecoming, of course, was often worse than the wait.

“He finally came out, but he was drunk. He was bare down to his overalls, and dirty. The white lightning made him mean, and he beat Momma a lot,” Mary writes. In addition, Terry generally returned penniless, having consumed his entire production of moonshine rather than selling it.

In search of work, Mary’s family moved as many as ten times a year, her father often taking farmhand positions. Farm living at least afforded the family better shelter and access to fresh produce. Inevitably, however, her father’s production and overconsumption of moonshine forced the family back to their isolated mountain cabin, which was devoid of electricity and plumbing.

Ultimately, Mary Judith Messer escaped the grim shackles of her impoverished mountain childhood. As for her father, he was eventually arrested and sentenced to the federal penitentiary in Tallahassee, Florida. Not that a hiccup like prison slowed him down. He gave up drinking his own product after a near-death experience, but he didn’t stop making moonshine until he became too old to tend the still.

While moonshine families like Mary’s struggled, progress gradually came to the Blue Ridge Mountains. Automobiles and passenger trains began bringing summer tourists eager to breathe the crisp mountain air. Magnificent resorts and boardinghouses promised unspoiled views and daily croquet and afternoon tea. And farming—that seemingly impossible endeavor that had turned so many to moonshining—made a comeback, thanks to technological advances in equipment that allowed for crop cultivation.

What hasn’t changed is the perseverance and never-say-die attitude characteristic of the people of the Blue Ridge Mountains. History, both good and bad, has evolved into folklore passed around at local hardware stores and farmers’ co-ops. But in these narratives are unmistakable lessons that have turned today’s residents into keen business people, even if meetings are still conducted in overalls and galoshes.

The landscape, too, has entered a new era of abundance. Wildflowers blanket hillsides, while the deep valleys are once again bountiful in elk, bear, and other wildlife nearly hunted to extinction in prior centuries.

In the end, the Blue Ridge Mountains are a sort of time capsule that whispers to us of the past. Cradled within the hillsides are hallowed reminders like dilapidated farmhouses, lone silos, and airless servant cabins. Adjacent to palatial modern mountain homes lie ridge-side cemeteries dotted with the primitive headstones of nameless men, women, and children who tried to augment a life in the midst of poverty and despair. But in a very real sense these forebears, like the mighty Cherokee Nation before them, will never be forgotten. Their spirits are alive today within their decedents, people who call the Blue Ridge Mountain home today—a living, breathing tribute that will never die.

— V —

The Cherokee Nation was a matrilineal society—a social order that designated stature and leadership determined by maternal lineage—in which descent is traced through the mother. In a societal structure of this kind, a tribe member would only be related to his or her mother and her ancestors, while the paternal lineage had little significance—making the women in the tribe quite powerful. Even the maternal uncles carried more importance than the fathers.

The Cherokee Nation comprised seven sacred clans: Anitsiskwa (Bird Clan), Anikawi (Deer Clan), Aniwaya (Wolf Clan), Anigatagewi (Wild Potato Clan), Anigilahi (the Long Hair), Anisahoni (Blue Paint Clan), and Aniwodi (Paint Clan). The seven clans lived harmoniously and burgeoned under civilized, central government.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE