vie-magazine-james-kernick-1

Name That Tune

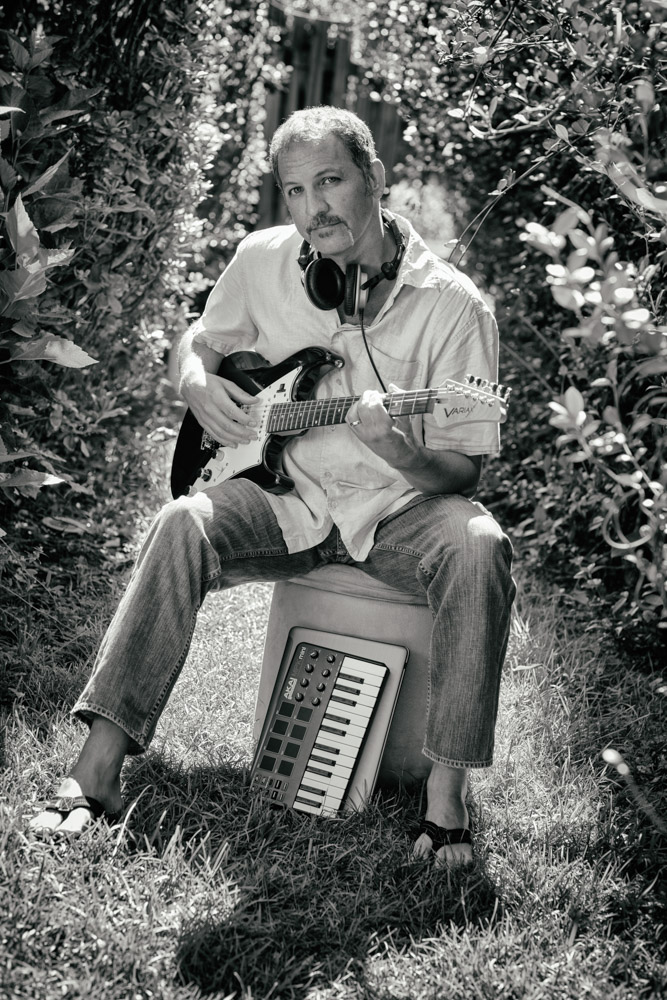

By Chad Thurman | Photography by Romona Robbins

If you’ve watched a television in the last decade, or lingered for a moment on any of the major TV networks, or made it a standing date with a friend or partner to tune in to any of the myriad TV shows viewers fervently claim as favorites these days, then you’ve probably, albeit unwittingly, heard the music of a composer whom you’ve most likely never heard of by name—James Kernick.

After eighteen years of dedicated and persistent effort, the Miramar Beach, Florida, composer can duly claim music credits for 232 television shows on over thirty major television networks airing in over forty countries. That’s a feat worth trumpeting about. His music has reached the ears and thus the senses of tens of millions—if not hundreds of millions—of people worldwide.

Kernick is a composer of production music. Also known as library or stock music, production music is essentially music licensed by publishing companies for use in multiple forms of media: television, film, radio, Internet, and others. The composer often creates music for these publishing companies on a work-for-hire, freelance basis.

Since early 2000, Kernick’s music has been a prominent part of propelling the Sturm und Drang of reality television, the excitement of sports recaps, the allure of televised fashion, the adventure of travel shows, and the intrigue of investigative dramas that many people watch religiously week after week, season after season.

His broadcast credits include integral music in popular prime-time television programs such as Project Runway, America’s Got Talent, E! News, ESPN College Football Saturday Primetime, America’s Next Top Model, Malcolm in the Middle, American Idol Rewind, The 700 Club, Shane Untamed, So You Think You Can Dance, E! True Hollywood Story, The Real World, and Road Rules, to name just some of them.

As consumers of videography, we can readily bring to mind the often grand music of a film’s opening scene. Most people recognize the opening to Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick famously and effectively made use of Richard Strauss’s “Sunrise”—a piece of music originally composed in 1896—to such effect that the obscure and somewhat anachronistic music instantly became recognizable at the end of the sixties as an auditory symbol of triumph and redemption. Moreover, what would the iconic crawl of the Star Wars opening be without the leitmotif of composer John Williams?

Think for a moment about the theme songs of TV shows like Friends or The Andy Griffith Show or even the The Benny Hill Show; you can probably hum or whistle a few bars, or at least you might be able to name the show upon hearing its musical theme.

Now let’s consider the short—often less than one minute—pieces of music found several times throughout a program. Consider the moment when the lights go down on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. Can you “hear” that moment in your mind? Would ESPN’s SportsCenter be the same without the electric guitar, heavy on the reverb sounds, accompanying those highlight replays? These shows would not be as entertaining or memorable without the incidental program music that often goes unnoticed by the average listener. How different television programming would be without this background music deftly propelling the show along!

The shows that make the money, some people tend to not respect you for, whereas I’ve done music for the esteemed NOVA on PBS—a show with Neil deGrasse Tyson—and I made pennies, something like forty-two cents!

Kernick started in the production music business in the mid-1990s along with his longtime musical partner and collaborator, Phil Francis. The two formed the musical collective known as PBJ Dungeon and quickly became very busy.

Around ’96 or ’97 we started buying the equipment (computers, digital recording devices, and instruments) and really getting into it. The computers really got fast around ’99, and then Sony ACID (a digital audio recording program) came out. Through a music placement service called TAXI, we got picked up by a music library in 2000; early 2001 was the first time we heard ourselves on TV. It was on the E! network, on a show called Rank with Brooke Burke. It was a nice repeating track; every time she came back on the show it played our song. We got fourteen plays in a thirty-minute show. It was a nice start-up to our career. That library went ahead and did another deal with us immediately, so we did more with them, and then things started spreading out. That was 2001. Then there were tip sheets—various music publishing services—where record labels and TV shows or people looking for music post their contact information along with the style of music they require. We discovered there was a tip sheet for Road Rules and they needed Middle Eastern music. So we sent a CD off with our four Middle Eastern songs, and then we just packed the rest of the CD with other songs. The CD made its way to the company Bunim/Murray Productions—they’re basically the pioneers of reality television. Since 2010 we’ve been composing exclusively with Bunin/Murray Productions. We are creative partners only, and they take care of all the business. They make their money in their publishing, and they have incentive to place us a lot, so it’s kind of a good thing.

With perseverance and music discerningly placed in popular TV programs, Kernick and Francis kept meeting the right people at the right time. In 2003, a piece was placed in a nationwide Verizon commercial.

We got into a couple of music libraries. We started out with OneMusic, a company started by Jim Long—a pioneer of early radio music—he heard one of our pieces of music and wanted to do a production deal with us. We did one, we did another; we got some good placements with him.

Although Francis now lives in Dover, Delaware, the two still work together remotely when the occasion arises.

With the Internet and a telephone these days you can do anything with music without having to send CDs. We used to pack up CDs and send them next day to LA. It was forty-two bucks to get them out as fast as possible. Now it’s just a click and there’s a digital transfer.

Kernick is wisely reserved, yet thankful, about his experiences with reality television.

A lot of my crowning achievements are things that some people frown upon. For example, I’ve been working with Keeping Up with the Kardashians since the inception of that show. We started out with that, but when I tell people this, some react in a negative way, saying things like “That’s some of the worst stuff on TV”; they put it down. The shows that make the money, some people tend to not respect you for, whereas I’ve done music for the esteemed NOVA on PBS—a show with Neil deGrasse Tyson—and I made pennies, something like forty-two cents!

The composer understands how the program music for reality television is vitally important to the flow of the episode. The proper composition, selection, and placement of this music can make or break the episode’s continuity.

The music supervisor of a show looks at my music and says, “Here’s a bunch to pick from,” and the editor finds one that is just right and puts in it there. With reality TV, it’s really important. With scripted television, there’s music, but not quite as much because it’s scripted and well done with good actors. Whereas with reality TV, the music is persuasive with what emotion you’re getting across. For example, in a reality show someone could get a bump on the head and that could come across as funny, or that they are mad, or it could be a moment of tension, and that’s where the music comes in. If it were a funny moment, I’d use a pizzicato, quirky, fun piece of music, but if the character gets mad, then that’s when the tension music comes in. It’s the same in film scoring, but with reality TV, it’s exceptionally important.

When Kernick and Francis began their careers, they initially set out to compose music for film, but quickly learned that within the genre of production music, they had something very much coveted in the music business—a unique sound.

Earlier on, that was our goal; we wanted to get into scoring specifically for film and TV, but the more we learned about it, we thought it would be better to do our thing and push our libraries. Our sound was different and it was working. We try to be focused on what we do; we target our music toward other shows. I have to keep cable on so I can watch bad TV to know what’s happening musically with these shows.

Despite turning away from film scoring and production, Kernick has still managed to have music included in the 2010 film Seeking Happily Ever After and the 2013 HBO documentary Valentine Road.

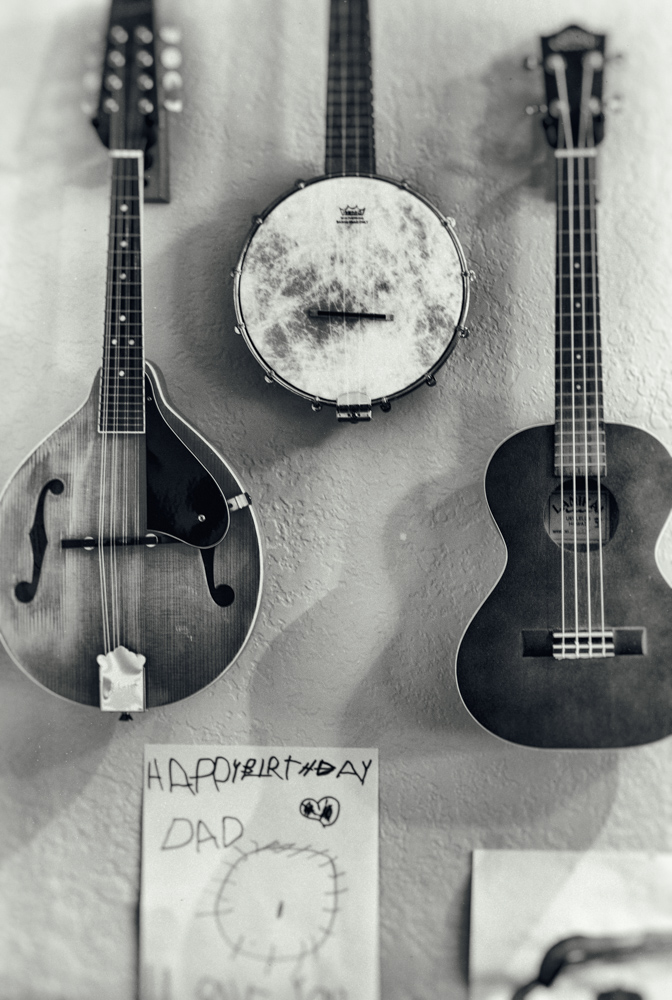

When composing, Kernick uses two platforms for creating and recording his music. His home studio consists of a recording computer and an audio monitoring system, digital and analog synthesizers, virtual instruments (performed with a synthesizer and rendered by a computer to sound like any instrument the composer requires), and many different acoustic instruments including, but not limited to, banjo, ukulele, and guitar.

The options for instruments and sounds is almost unlimited these days, so, depending on the project, I make an effort to either keep the track “pure” to the style or create a hybrid of styles. Right now, hip-hop rhythms with orchestral elements are in big demand. A big epic, orchestral, techno-hybrid ending will top off these tracks perfectly, and makes it ready for a dramatic scene change, a cut to commercial, or an episode ending.

I have two directions I compose in—composing in a specific musical style or composing freely through improvisation; although usually I’m still leaning towards a TV-friendly piece of music even if it’s experimental, bizarre, or just plain vacuous. You never know when a more “off the wall” piece is going to become a heavily played TV piece. A bit of trial and error, I suppose.

If I’m composing a requested or “high demand” specific style and/or mood, I often listen to snippets of successful or inspiring examples of the style I’m going for. Once I feel I have a good idea of the vibe and the instrumentation needed, I’ll find an appropriate tempo. If I’m writing in an orchestral style, I’ll use a click track (for tempo) and start trying ideas with pizzicato strings and bass. This usually is enough to create a good backbone for the track. I’ll then usually work in a melody idea with a clarinet, celesta, or other bright instrument. Once there’s a harmonic base and good melody to develop on, I’ll start an arrangement and see what elements should go where. It’s usually a build up from the most simple, catchy elements, to a full interplay of all the elements. Dynamic variations are very advantageous when placing music to video. And, most importantly, I try to build up to a nice solid, proper song ending. Having a good dramatic or fun “sting” ending is very important for visual scene changes and “act outs” for commercial breaks.

Kernick spends approximately two months every year in Europe at his family farmhouse in the tiny village of Vysočany, in the Czech Republic. He has composed in Jena, Germany; Prague and Pilsen, the Czech Republic; Almería, Spain; Paris, France; and Amsterdam, the Netherlands, as well as in Montreal, Quebec.

When traveling, I have to cut my studio down to very basics. I’ll have a laptop, a very small keyboard, headphones, and a guitar. It’s limited compared to my home studio, but being limited and out of my element often brings out some very good results. This is all possible because of the truly amazing music software available. It’s incredible what you can create inside the computer. And you can keep that warm organic, human sound if you treat it just right. Of course, when traveling, I miss my real acoustic instruments.

I can travel and write. I write a lot on the road. I once composed a piece on a keyboard and laptop in the bulkhead of a plane! I write better in different settings; the music does not necessarily always reflect the area. For example, we have a renovated farmhouse in Vysočany in western Bohemia in the Czech Republic—the former Sudetenland. It’s at the end of the road, out in the middle of nowhere, very quiet and peaceful. I’ve written music there that was not reflective of the surroundings; it was harsh and certainly not peaceful. Sometimes the less you have, the better the stuff you come up with; getting out of your element is good for you.

Being a professional composer in today’s digital world means that for the artist to find success, he or she often ends up taking on more than one role in the creative process. This is something that Kernick accepts and uses to his advantage.

Writing, arranging, and orchestrating the music is only half the battle. Having professional-sounding music is a must. This puts me in the position of composer, producer, and studio engineer—a veritable one-man band. In this age of incredible music software, I find it nice to keep my music on the warm, analog, organic, and human side. That’s an art in itself. There’s a place for cold, digital machine music, but generally people are going to lean towards more natural and ubiquitous sounds. I don’t see a good-sounding piano or guitar going out of style any time soon.

The next time you are watching TV, take notice of the sounds that are an integral part of moving the action or dialogue forward. Notice how prominent yet inconspicuous this music is. What some call “background music” will now suddenly come to the foreground of your awareness, and you’ll have a newfound frame of reference for enjoying your favorite TV shows.

And now back to your regularly scheduled program.

— V —

To hear some of Kernick’s music, visit www.soundcloud.com/james-kernick-music.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE