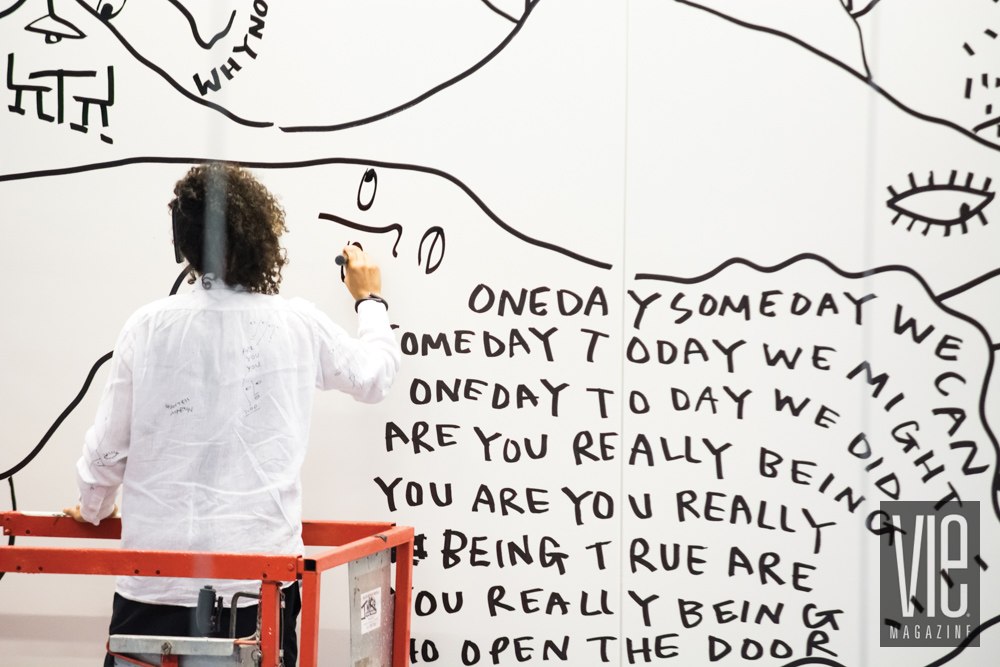

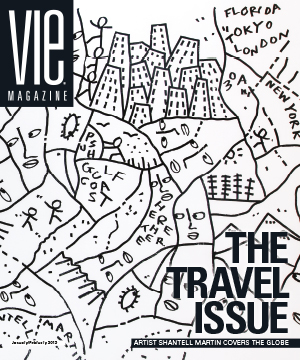

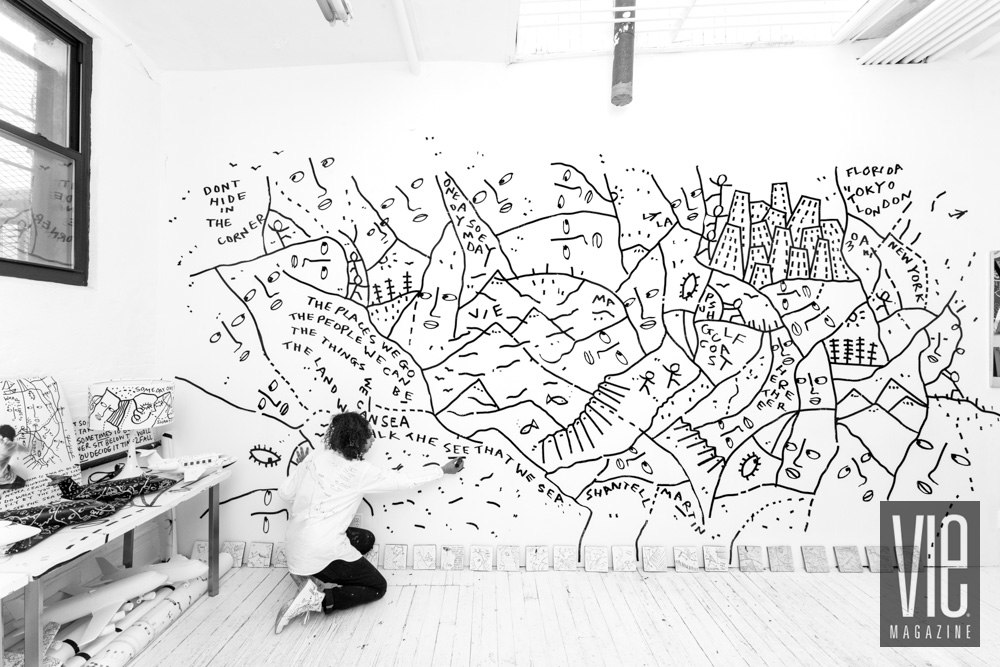

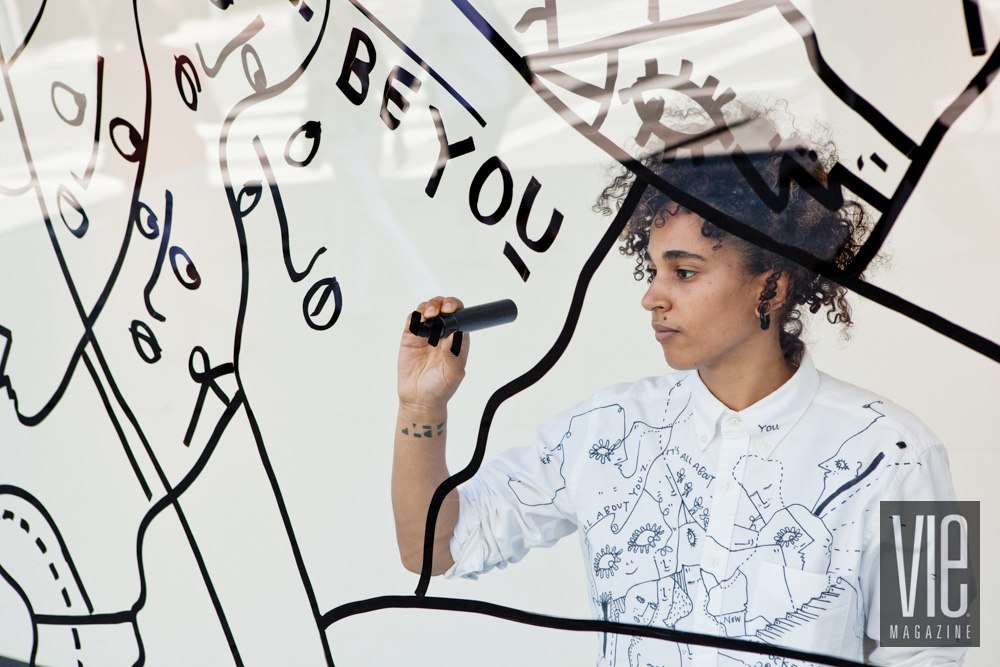

Artist Shantell Martin works on a collaborative project at interior designer Kelly Wearstler’s studio in Los Angeles. Photo by Meghan Beierle

Life in Black and White

By Tori Phelps | Photography by Roy Rochlin

Artist Shantell Martin’s black-on-white drawings pop up in unexpected places—cars, clothing, chairs—asking questions like “Who are you?” and sharing a few of the answers Martin has discovered for herself.

The first thing to know about Shantell Martin is that you don’t know anything. To prove it, she flashes a photo of herself as a nine-year-old surrounded by her five younger siblings. It looks like an ad for a Scandinavian holiday, complete with blond, blue-eyed children as far as the eye can see. Until the eye lands on Shantell. The point? Everyone has assumptions about other people—where they’re from, what their families look like—and they’re usually wrong.

It’s not a card she plays as a parlor trick-cum-artistic statement. Funny and genuine, Martin is refreshingly free of any angsty pretension one might expect, and even forgive, in an artist of her caliber. It’s just her way of starting with a clean slate.

In fact, Martin starts most days with a clean slate. Her signature artwork involves black ink on a white surface—any white surface—therefore, Martin usually can be found surrounded by lots of crisp white surfaces. Whether it’s a wall, a car, or the white shirt she’s wearing, any area can be transformed into a provocative artwork, complete with grab-life-by-the-horns prompts like “go” and “now.”

Martin is all about the now, vocal in her desire to look forward rather than back. She grew up in a southeast London community known as Thamesmead, which was built as a model of utopia, but, instead, became a hard-knock destination. It even served as the film backdrop for A Clockwork Orange. As to the happiness of her own family, Martin muses, “I don’t know that there are a lot of happy families.”

There were plenty of good times, Martin insists, but there was also no escaping the fact that she looked different from everyone else, both inside and outside her house. At a time when fitting in is most important, she didn’t. Now, she sees that as a positive thing. “It was my first passport,” she says. “Because I didn’t look like everyone else, I didn’t have that pressure to fit in. It allowed me to do what I wanted to do.”

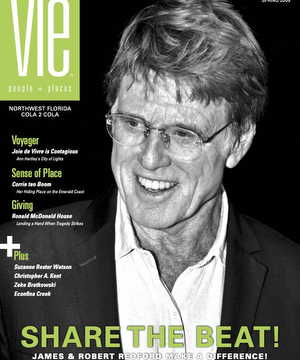

Martin works on a mural in her New York studio, exploring the subject of “travel” for the cover of VIE.

Photo by Roy Rochlin

And what Martin wanted to do was draw. From an early age, drawing gave her some control over her environment. At first, she drew people and created backstories for them, satisfying her desire to make things appear as if she were controlling them. Later, art became a way of dealing with her feelings when she didn’t know what else to do with them.

Martin not only enjoyed drawing, she was good at it. She earned a spot at the prestigious Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, where she flourished artistically and personally. Among these art students, most of whom reveled in their outsider look and attitude, she finally fit in. “I really enjoyed being around people where being an individual was celebrated,” she smiles.

She graduated with first-class honors and, for the first time in her life, she felt pressure. Lots of it. Martin didn’t believe it was possible for her to be a full-time artist; that was only for the lucky or the rich, neither of which she considered herself to be. Her solution? Move to Japan.

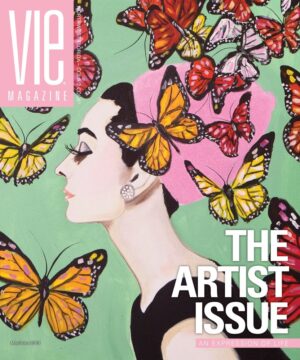

A stitched design collaboration between Shantell and her grandmother, Dot Martin.

Photo courtesy of Shantell Martin

Martin developed an infatuation with Japan through an art school friend who hailed from the country. She decided that packing her bags for Japan to teach English would accomplish the dual goals of indulging her interest in Japan while also escaping the pressure of graduating with highest honors from a famous art school. As it turned out, the differences were more than she could take. She didn’t mind the new culture or even the language barrier, but she couldn’t get used to her placement in a relatively remote area of Japan. For a woman who was raised—and thrived—in a concrete jungle, living in the countryside was unbearable.

Martin got a new job teaching English in a Tokyo suburb, and though she loved her young students, she still didn’t feel close enough to the action. The only solution was Tokyo itself, where she was hired to teach business and presentation English. A much happier Martin was making new friends, one of whom was an event planner who invited Martin to do live drawing at one of her events. Martin accepted and decided that, rather than the usual artist-drawing-in-a-corner routine, she would draw under a camcorder and project the evolving image onto a wall. That night was the beginning of her self-described “accidental career” as an artist in Tokyo.

The timing was perfect. “After art school, I didn’t want to do art; I needed a break,” she says. “That year and a half of teaching was enough time for me to get some space and figure out that, yes, I do want to do art.”

Martin found that she loved creating in real time, which was good because she was suddenly in demand. At first, she performed mainly in Tokyo’s popular underground clubs with just her sketchbook and a projector. Soon she was invited to provide visuals at bigger clubs, where she used a computer and then-new drawing software. And, though she was physically separated from the patrons, Martin found a way to connect with them through her drawing; in the process, she shaped a new kind of experience for the city’s clubgoers. “At the time, visuals were in the background,” Martin says. “They weren’t created in real time and had no connection to that specific experience. But if I saw people I knew at the club, I would write their names on the screen. And if the crowd went ‘woo,’ I wrote ‘woo.’”

If you’re not thinking while you’re drawing, you’re

just being you and letting that come out.

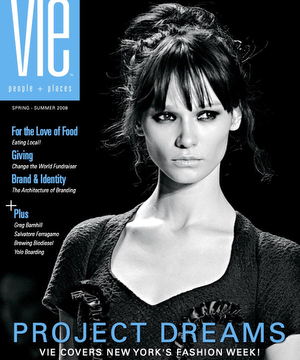

Martin takes her motto of “drawing on everything” quite literally at a solo show in the

Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts in Brooklyn, New York.

Photo by Roy Rochlin

In effect, she brought visuals from the background into the foreground, and the artistic world took notice. DJ Mag, a highly respected European magazine, repeatedly voted Martin among the top ten VJs in the world. It was a double-edged sword for her. Because she was breaking new ground, her inclusion prompted heated debate about whether she was a real VJ. But that discussion also drew more attention to her work, leading to more gigs.

Not quite ready for or comfortable with the success she had achieved, Martin again made her escape—this time to New York City. She thought she would simply move her Tokyo life to New York, but she discovered that was impossible because the Big Apple didn’t know much about Martin’s style of art. “They tell you that New York has everything, but not if you’re moving from Tokyo.”

Digital Graffiti at Alys Beach, Florida, has been a unique opportunity for Martin

to interact with her audience and show off her talents since 2009.

Photo by Bill Weckel

That pen began drawing everywhere: on cars, on walls, on people. She was experiencing an artistic renaissance, but she also needed to pay the bills. Luckily, Digital Graffiti came calling. Organizers of the Alys Beach–based projection art show saw a DVD of Martin’s work and asked her to participate in the 2009 event. The experience proved so successful for both parties that Martin has returned every year, and will return to participate in Alys Beach’s Visiting Artist in Residency program in January 2015.

Not only did Digital Graffiti open doors for Martin in America, but beautiful South Walton Beach also inspired her artistically. It was here that she decided to rescue bottles from the area, paint them white, and draw on them with her signature black pen. Some of those bottles ended up in a show where the public had a rare opportunity to buy a Shantell Martin original. Apart from a limited line she launched recently with international designer Kelly Wearstler, which features Martin’s hand illustrations on products ranging from clothing to home decor, it’s been nearly impossible to own Martin’s artwork.

Martin has focused mainly on wall commissions for high-profile New York companies, as well as museum exhibitions. She initially wanted to be involved with the gallery scene but discovered a catch-22: galleries wouldn’t show her work if other galleries hadn’t shown her work. Her commercial emphasis has left plenty of time and inspiration to create hundreds of pieces for herself, which she’s considering making available for purchase. “It has to be in a way where I have control over it,” she stipulates. “I care about my work, where it goes, and who it goes to.”

She’s considering an application form where potential clients can tell her why they want the piece and what it will bring to their lives. Martin sees it not only as a vetting process, but also as a step toward building a relationship between artist and collector. No doubt admirers salivating at the prospect of finally being able to acquire her work will be more than happy to fill out an application. For her many fans, color is highly overrated.

In a very real way, Martin has lived several different artistic lives. The most obvious evidence is the fact that different audiences would tell you vastly different stories about her work. She points out, for example, that Japanese friends would classify her art as colorful and animated, while Americans know her for stark, black-and-white creations.

The truth may lie somewhere in the middle.

The idea there is that you master one tool or one craft before you move onto anything else,” she explains. “For me, I don’t know if it’s about mastering a pen as much as mastering a line.

Stateside fans may be surprised to learn that Martin enjoys using color but only feels it’s appropriate in a collaborative relationship, like the one with her grandmother, Dot Martin, who needlepoints Shantell’s words in London and sends them to her in New York. “It could be in a club where people are dancing and bringing color to the visuals,” she says. “Or it could be when I’m drawing on someone, and they bring their own color to the work.”

When it’s just Martin and a canvas, she prefers a simple black line. Rather than overwhelm a viewer, black-and-white art makes you want to spend time with it, she believes. “Sometimes color is too easy. When you see a colorful drawing, you say, ‘Oh, that’s pretty,’ and walk away,” she notes. “When it’s black and white, everyone is initially drawn to a different starting place. I’m not dictating anything; I’m leaving room for discovery.”

A pen has been Martin’s trusty sidekick since she was a child. When other kids were drawing with pencil, she was already gravitating toward pen, which didn’t leave messy eraser marks on the paper and required you to live with your mistakes. Now, she also appreciates that her tool of choice beautifully complements her globe-trotting lifestyle: just throw it in a pocket and go. Her time in Japan, too, taught her to stick with a medium until she’d conquered it. “The idea there is that you master one tool or one craft before you move onto anything else,” she explains. “For me, I don’t know if it’s about mastering a pen as much as mastering a line. People don’t realize what it takes to make a line look and feel right.”

She’s schooling other artists in confident lines as well. Building on her teaching background in Asia, Martin now instructs a graduate class at NYU each spring in a course appropriately titled Drawing on Everything. It’s not a class that teaches you how to draw, she clarifies. Rather, it’s intended to help students find their unique style and pull it out of themselves—much in the same way Martin’s time in Japan did for her. Through exercises and collaborative work, her students learn to work intuitively and spontaneously. “I get them to do stuff they’re not thinking about,” she says. “They’re just making art.”

During the last part of 2014, Martin also served as a visiting scholar in the Social Computing area of MIT’s Media Lab. It’s a place for researching and creating social models, such as affordable schooling for children. Martin is collaborating on some projects while also focusing on her own work, which combines data with lines and drawing. “One thing I’ve started to do is take the amount of street in some cities and draw the equivalent amount of that street as an abstract way to represent different kinds of data,” she says.

If that doesn’t compute with you, the takeaway is that Martin is not only a brilliant artist; she’s just plain brilliant. Columbia University certainly thinks so. The school invited Martin to be a fellow at its Brown Institute for Media Innovation in 2015.

I like to watch people look at my work, without them realizing I’m there. People usually smile when they see it, and I hope they take some of that away with them.

Martin shares an important message in this mural on glass at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto.

Photo by Connie Tsang

With so much on her plate, it’s no wonder Martin’s biggest challenge right now is finishing projects—or even starting the ones rolling around in her head. She knows she needs help in the form of a team, but it’s tough for her to think about going from Shantell the individual to Team Martin. “Other artists have managers and assistants, and I know it has to happen,” she says. “I’m a little resistant to that because I want to find a really good team who wants to work with me and vice versa. But I know it has to happen; there’s only so much one person can do.”

Martin clearly knows her limits. But she also knows how high she can fly. She’s created a philosophy for herself that’s made its way into many of her pieces. Martin pulls out small rectangular stickers with the words “Who Are You” stacked on top of each other. She covers all but the first letter of each word to reveal WAY. She does the same with a piece of paper containing the words “You Are You”: YAY. “A lot of people say my drawings resemble maps,” she says. “So this philosophy is all about trying to find your way in life—what you do, what you love, what makes you tick, and what you can share with the world. And then celebrate that. Yay.”

Martin works on a mural in a stairwell at Columbia University in New York, where she will

be a 2015 fellow at the Brown Institute for Media Innovation.

Photo by Roy Rochlin

It’s not something that’s come easily for Martin. Today she can reel off a long list of things she likes—and likes about herself—but she admits it’s taken a lot of hard work to get here. “Maybe at some point in the future I won’t like myself again, but at least I know I can get back to the point where I can celebrate who I am,” she says.

Speaking of who she is, it’s tempting to draw parallels between the fact that Martin works in black and white, wears black and white—and is black and white. “It’s not intentional,” she insists of the outward expressions of her biracial background. “If it’s a cosmic coincidence, it’s a nice one.”

It’s certainly not a coincidence that people seem to take joy in her work, a reflection, Martin hopes, of the joy she puts into creating it. “I like to watch people look at my work, without them realizing I’m there,” she confesses. “People usually smile when they see it, and I hope they take some of that away with them.”

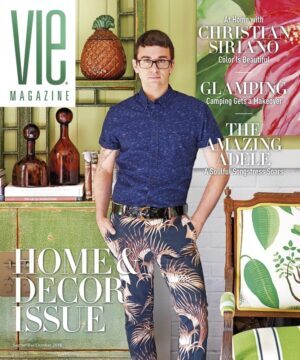

On the Cover

Martin draws on other people’s walls for a living, but her own studio walls had remained stubbornly white. “I like it to be blank when I come in,” she explains, “with nothing from previous projects bleeding over into new work.” She broke that rule for VIE, however, allowing the idea of travel—one of her favorite topics—to express itself through her pen on her New York City studio walls.

She starts the project the same way she does any of her work: by sketching out a framework of the piece on the wall. As she moves back and forth—adding, changing, expanding, and getting a boost from her step stool when necessary—her marks seem random. But it clearly makes sense to her and, after a short time, to observers as well. It’s a rare treat to watch an artist in the process of creating, and Martin’s movements are so intuitive that she can talk and laugh throughout the design.

Before long, she says she’s almost done. How does she know? “You feel it,” she says. “It starts here,” she says, gesturing to her shins, “and right now it’s about here,” she concludes, pointing to her chest. Sure enough, after another five minutes she stops working and steps back. “Good,” she pronounces in her lilting accent.

Martin draws on patrons at the Are You You solo art event at MoCADA in Brooklyn. Photos by Roy Rochlin

More than good, most would argue; Martin has created her unique brand of magic. With images of her own travel experiences and ocean-spanning moves as inspiration, she incorporates references to Florida’s Gulf Coast, Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York, and Massachusetts into her wall mural. She insists that traveling is a conversation with yourself as well as with people you meet, so she integrates plenty of people and faces into this drawing. “It summarizes the idea that traveling is a way to meet people, discover, and explore. That’s what all these people are up to,” she explains, waving her hand over the wall. “They’re curious, they’re intrigued, and they’re learning new stuff.”

And, like nearly all of Martin’s works, this one contains a not-so-hidden challenge. “Don’t hide in the corner” is written—where else—in the corner. “It’s a reminder to get out and try new things,” she says.

VIE SPEAKS — Shantell Martin from VIEzine on Vimeo.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE