vie-magazine-hero-corrie-ten-boom-2009

Her Hiding Place on the Emerald Coast

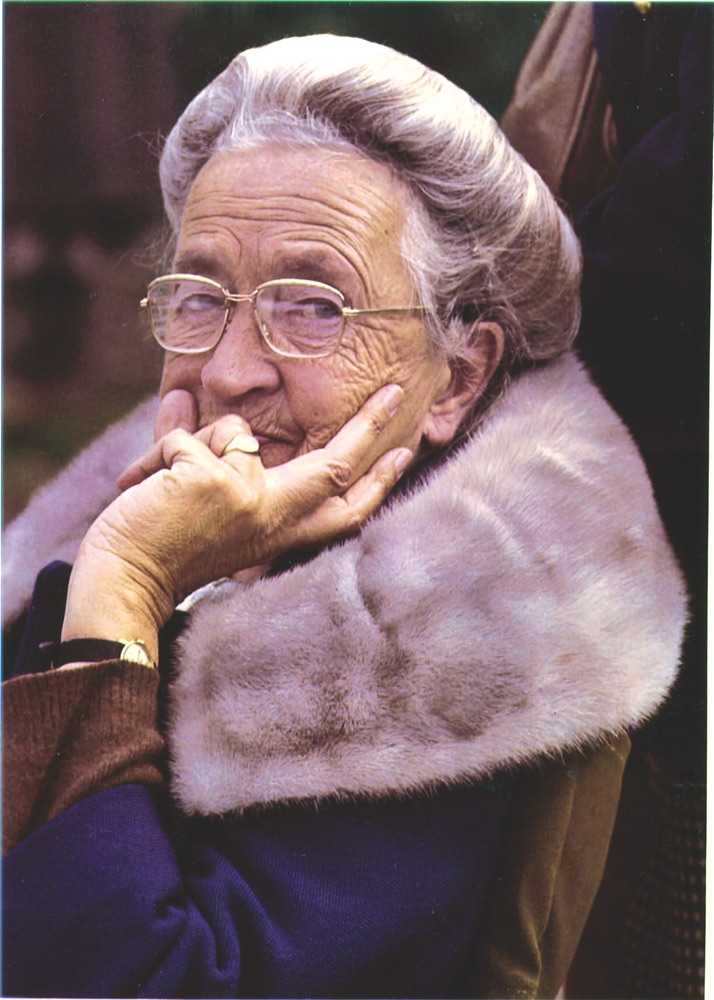

Corrie ten Boom (1892-1983)

by Quin Moore Sherrer

Corrie ten Boom helped to rescue many people from certain death at the hands of the Nazi SS during their occupation of the Netherlands. At age 53, after her release from a concentration camp, Corrie began a worldwide ministry which took her into more than 60 countries in 33 years—it also brought her to our Emerald Coast.

A hiding place! Thousands have come to the Emerald Coast seeking a hidden place for rest, recreation, and even some soul-searching. One special lady who delighted in calling this area her “hideaway” for respite and for writing books for almost a decade was the famous Dutch heroine Corrie ten Boom. Her leadership in the Resistance when the Nazis occupied the Netherlands during World War II and her subsequent imprisonment are chronicled in the highly acclaimed movie, The Hiding Place. More than six million people have read her story in the book by the same name.

In 1943 and into 1944, Corrie, her family and friends saved the lives of an estimated 800 Jews and protected untold numbers of their countrymen serving in the Dutch underground. Members of the Ten Boom family, who were Christian, were sent to German concentration camps for their part in saving lives with the only weapon they had—love.

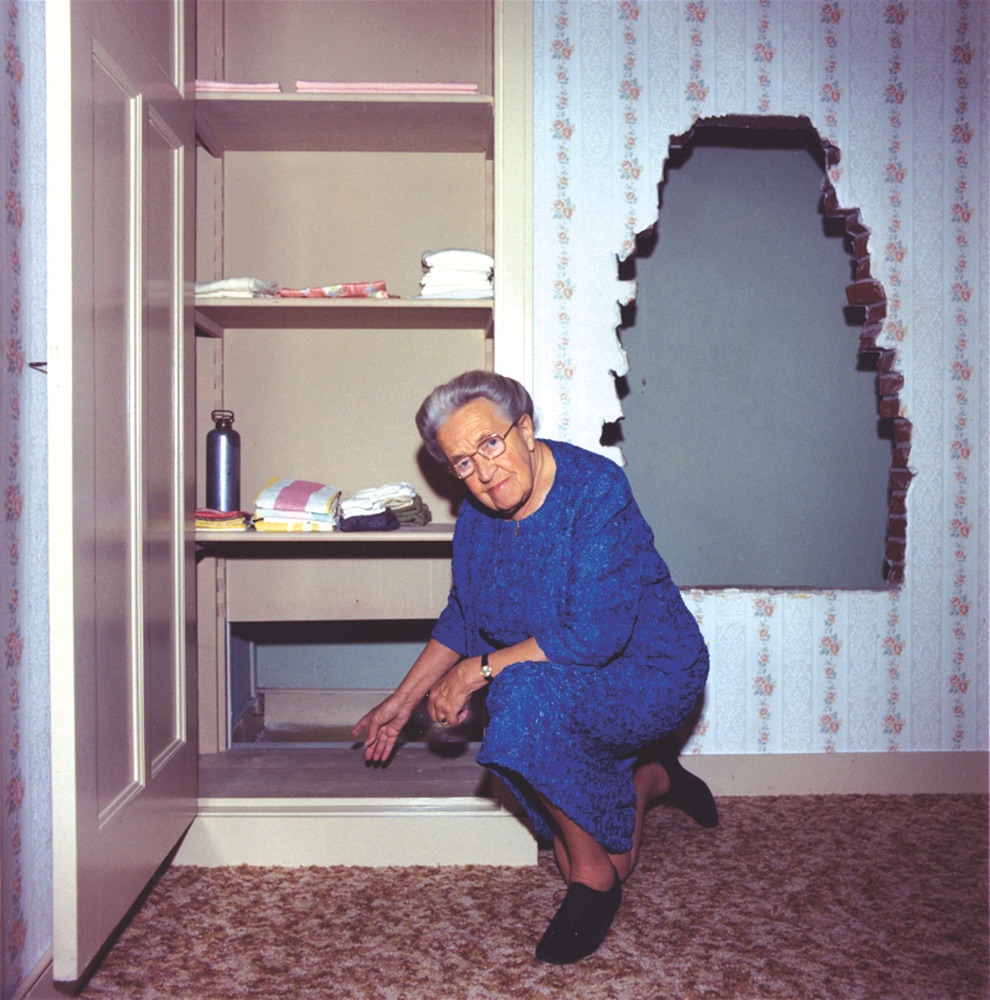

At age 50, Corrie became a ringleader for helping people escape the dreaded Gestapo, working in her father Casper’s watch shop on the first floor of their home in Haarlem, the Netherlands. Upstairs, in Corrie’s bedroom, a false wall hid the “jewels” for whom Hitler’s soldiers hunted while Corrie searched for “safe houses” for them in the countryside. Materials to build that secret room were smuggled into the home, little by little, in an old grandfather clock case.

The Friendship Begins

But how, you may wonder, did this unassuming elderly woman, Netherlands’ first licensed female watchmaker by trade, find her way to our area in her latter years? Was it the lure of our blue-green Gulf and peaceful waterways reminding her of her native Netherlands? Yes, partly. But it actually stemmed from a friendship with a local couple who retired here: Dr. Mike and Fran Ewing. They had met Corrie while living in Charlottesville, Virginia, not too long after she first started coming to America to lecture about her time as a prisoner during the war.

Corrie ten Boom – Photo courtesy of Quin Sherrer

One day in 1962, they heard that an elderly woman who was a Holocaust survivor was going to speak at a church in Washington, D.C. at the invitation of the Chaplain of the U.S. Senate, Richard Halverson. Curious, yet impressed, they decided to drive up to hear her.

Now, Mike and Fran themselves were no ordinary couple. When Mike was a thirty-two-year-old doctor in the U.S. Army, he contracted polio which left him paralyzed in both legs and arms, with just a little mobility in his right hand. After years of rehabilitation and retraining in a new field of medicine, he was serving on the medical school faculty at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. His wife, Fran, a physical therapist, also worked there.

The night they heard Corrie speak was a watershed moment for them both. Afterwards, Fran pushed Mike’s wheelchair up so that they could tell Miss ten Boom how much they enjoyed her message. Corrie took one of Mike’s hands and one of Fran’s, and with her bright blue eyes wide open, looked toward heaven and prayed for them. “We were blown away by that—because no one had ever done such a thing for us before,” Fran remembers. That night a friendship was born that brought Corrie into their lives and their home for the next 16 years.

Starting in 1963 and continuing for the next three years, Fran set up meetings in Virginia for Corrie to speak about the Holocaust. Each time, she would stay with them. In 1966, Mike and Fran moved to Atlanta where Mike was on the faculty at the Emory School of Medicine. Again, Corrie came as often as she could and made their home hers. Between visits, she and her nurse-companion, Ellen de Kroon, traipsed around the world as Corrie spoke about how God’s love had enabled her to forgive her former captors.

Then, in 1969, Mike received what he thought was a death sentence—Lou Gehrig’s disease. He and Fran moved near Destin for one of the most marvelous years of their lives.

Corrie ten Boom’s Family – Photo Credit: Archives of the Billy Graham Center, Wheaton, Illinois.

“Let’s make it as fun as we can make it,” Mike told Fran when he believed he had less than a year to live. They bought a huge travel trailer, parked it at Crystal Beach near the Gulf, and spent happy-filled days fishing from the old wooden pier. Mike’s health took an upturn from the rest, fresh air, and sunshine. He later learned that he had been suffering from post-polio syndrome, not Lou Gehrig’s disease. After a year at Crystal Beach, they made another key move.

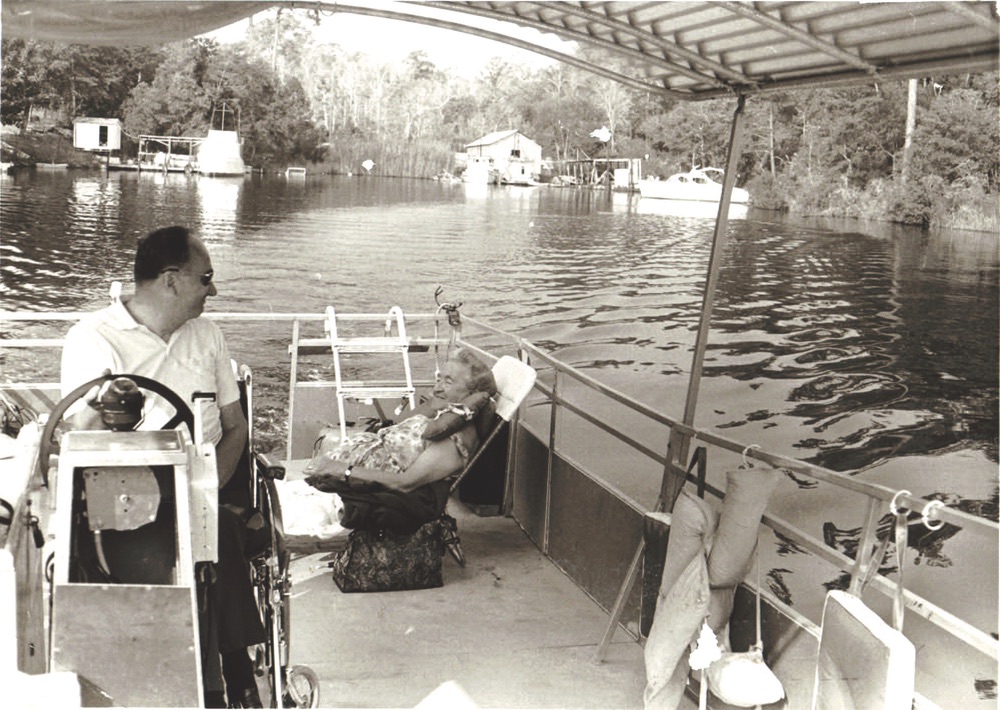

They built a home in Valparaiso on Tom’s Bayou, with its nearby smooth waterways, and bought a big pontoon boat to anchor at their dock. Mike could easily roll his wheelchair onto the boat and captain it himself, using his one good hand. The boat provided Fran, Mike, Corrie and her secretary, Ellen, with untold hours of pleasure.

Again, the Ewings kept a spacious bedroom always ready for Corrie’s visits. “Don’t change anything in my room. I want everything just the same, so when I am coming home—I can know I’m really home, here in my room,” she told Fran.

Ellen, her secretary for nine of those years, recently commented on that time. “Corrie and I had wonderful, peaceful times at Fran and Mike’s in Florida back then,” she told me. “Fran was an excellent cook. She and I used to laugh because Corrie thought she was hidden back in her own cozy bedroom, but because of the terrazzo floors built specifically for Mike’s wheelchair, we could hear Corrie every time she walked about—so she really wasn’t hidden from us,” she laughed.

Several professional authors, such as John and Elizabeth Sherill (The Hiding Place) and Jamie Buckingham (Tramp for the Lord), wrote books about Corrie in those days. Corrie herself continued writing smaller teaching books. Propped up on pillows in her bedroom in the Ewing home in Valparaiso, she wrote each morning after her breakfast of tea, fresh fruit and toast.

Ellen then typed the notes Corrie had written in her spiral notebooks and Fran often helped edit the final manuscripts. Corrie also sorted through piles of mail each day, trying to decide which speaking invitations to accept; she was often booked for up to two years in advance. A ten- to twenty-minute nap each afternoon was all she required to feel refreshed.

While here, Corrie spoke in private homes, community churches, civic centers and wherever else Fran could arrange her meetings. “Her talks transformed my life,” says Pat Hodges who still lives in the area.

Whenever another of her books was published, Corrie wanted to celebrate by eating in Destin at “that big round restaurant”—meaning the revolving restaurant on the top floor of the Holiday Inn.

She loved leisurely times sitting in the sun on Mike and Fran’s patio, taking short walks twice a day, and watching sunsets over the bayou.

To help her unwind, Corrie enjoyed playing chess. So when she asked, Mike rolled his wheelchair to the dining room table to challenge her to a game. Amazingly, they were well matched, playing almost game for game. “Mike, I like to play chess with you better than anybody on earth,” she’d say with a smile when she beat him.

Corrie was old enough to be Mike’s mother, but she didn’t want to be treated like “a double-old grandmother,” as they called her in some countries. Mike, every bit the independent-thinking intellectual, would sit for hours in the evenings listening to Corrie share stories while they played chess.

Twice in 1973, the Ewings flew to Europe to visit Corrie in Holland. She was as excited as a kid with a new toy as she showed off her hometown of Haarlem, lined with its canals and quaint narrow row houses.

An exhilarating, never-to-be-forgotten moment came in 1975 when the movie about her life, The Hiding Place, was released by World Wide Pictures for its premier showing. It had been filmed on location in Holland with Corrie watching from the sidelines and offering her suggestions. Fran and Mike flew to California for the premiere.

“Corrie could hardly contain her excitement,” Fran remembers. “Almost from the moment the movie started, Corrie’s eyes misted with tears. By the time it ended, Corrie was sobbing. The great singer Ethel Walters rose from her wheelchair, walked over, put an arm on Corrie’s shoulder and began to sing “His Eye is on the Sparrow.” “I don’t think there was a dry eye in the place after that,” Fran continued. In the film, Jeannette Clift played Corrie, Julie Harris, her sister Betsie and Arthur O’Connell played Papa ten Boom.

Photo Credit: Used by permission of the Corrie ten Boom House Foundation, Haarlem, The Netherlands.

Corrie was at ease talking to a prisoner, an airport porter or even a well-known person like Evangelist Billy Graham, who became her friend. In fact, Corrie was a guest speaker for him at one of the Billy Graham Crusades, where he publicized her book The Hiding Place.

Fran remembers of Corrie, “She was highly intelligent, modest and gifted at telling stories in such a simple way anyone could understand. She was comfortable with us because we were casual, very open and often had people living with us, as had Corrie’s family. We just made her part of our family until 1978 when she got too sick to come again.”

The Beje (Ten Boom family house) Photo Credit: Used by permission of the Corrie ten Boom House Foundation, Haarlem, The Netherlands.

However, in 1976, at the age of 84, Corrie and her assistant, Ellen, embarked on a seven-month speaking tour that took them into eighteen cities in the United States. Billy Graham convinced her to settle down and stop her hectic pace. So, in 1977 Corrie and her new assistant, Pam Roswell, moved into a house in Orange County, California. But she didn’t slow down much. Over the next two years, she wrote five new books and finished five teaching tapes. Her ministry finally ended when she suffered a stroke. Other strokes followed, partially paralyzing her. She spent her remaining days in California.

Corrie died in California on April 15, 1983—her 91st birthday. Mike died at home in Niceville on November 1, 2007 on his 87th birthday—after 55 years in a wheelchair. Fran continues to live in a waterfront home in this area.

Soon after Corrie’s death, a precious package was delivered to the Ewing home. Inside were two items she had bequeathed them: her gold signet ring for Fran and an intricate colorful tapestry for Mike which she had been cross-stitching the last time they had seen her. Earlier Corrie had given them another keepsake—a silhouette cutting made by the first Jew who the Ten Boom family had hidden in their home.

From left to right: Corrie ten Boom, Ellen Stamps, Fran and Mike Ewing – Photo courtesy of Quin Sherrer

Corrie’s Heart for the Hopeless

The Béje was the affectionate name of the home in Haarlem where Corrie grew up as the youngest of four children. Their father, Casper, known as Opa to the townspeople, sold and repaired clocks in his watch shop on the first floor of their home. Three older aunts shared the house.

The family regularly provided meals to the homeless and they took in at least a dozen foster children. For years, Corrie worked among mentally challenged children. She also started a type of Girl Guides club for young women, which spread throughout Holland.

Corrie never married, and eventually joined her father’s repair business, becoming the first licensed woman watchmaker in the Netherlands.

After the German occupation of her country, she was suddenly thrust into a new mission: to help save lives.

Often, six or seven people lived illegally in her family’s home, while others stayed only a short time until other courageous Dutch families offered shelter. As the word spread, dozens came in and out of the Ten Boom watch shop daily, seeking sanctuary. As quickly as Corrie found places for them, more arrived.

After a year and a half, the Ten Boom home developed into the center of an underground ring that reached throughout Holland. Corrie found herself dealing with hundreds of stolen ration cards each month to feed those in hiding.

Then it happened! On February 28, 1944, the Ten Boom family was betrayed by a fellow Dutchman they had befriended. The Nazi secret police raided their home and arrested about 35 people. Among them were Corrie’s 84-year-old father, Casper, Corrie, her sisters, Betsie and Nollie, her brother, Willem and her nephew, Peter; they were all transported to various prisons.

When Casper “Opa” ten Boom was warned about the dangers involved in rescuing and hiding Jews, he replied, “If I die in prison, it will be an honor to have given my life for God’s ancient people.” After only 10 days in Scheveningen prison, the 84-year-old patriarch did die and his body was dumped into a pauper’s grave. Shortly after Corrie and her sister, Betsie, were sent to Ravensbruck, their third concentration camp, in December of 1944, where Betsie died.

Corrie was released a short time later through a clerical error—one week before all of the other women her age were killed. Her brother, Willem, came down with tuberculosis in prison and died shortly after his release. Other relatives, including a nephew, never came home.

During nights in prison, when guards stayed away from their barracks because of flea and lice infestations, Corrie read a smuggled Bible to the other women prisoners. Just before Betsie died, she told Corrie, “You must tell people when you get out that there is no pit so deep that God’s love is not deeper still.”

The words rang in Corrie’s ears and stayed in her heart. After the war, Corrie tried to go back to repairing clocks but prison life had drastically affected her. She quickly penned her first book, “A Prisoner and Yet…” Burning with empathy for those who had survived the death camps, Corrie dreamed of a place for them to be healed from their scars and memories.

A spacious home for such a retreat was suddenly given to her by a Dutch woman who heard her speak. Soon thereafter, Corrie was not only working for the rehabilitation of those traumatized by the war, but she began giving short talks about her own experiences. Her speeches were usually about allowing love and forgiveness to transform the heart.

Soon she was traveling the world—going into more than 60 countries in 33 years—speaking to audiences in prisons, churches and courtyards from Africa to Vietnam, Russia to Cuba. Corrie was knighted by the Queen of the Netherlands for service to her nation.

Mike Ewing and Corrie ten Boom – Photo courtesy of Quin Sherrer

Forgiveness Sets You Free

I first met Corrie when she took a beachside cottage near Melbourne, Florida to collaborate with my writing mentor Jamie Buckingham on her book, Tramp for the Lord. Naturally, I attended her lectures too. One afternoon I heard her tell the audience of her early struggle to overcome hatred and to forgive not only the man who had betrayed her family, but the German guards who were so cruel to her in prison. She recounted the following story that day.

It was 1947, and Corrie had gone to defeated Germany to speak at a church. After her lecture, a balding, heavyset man in a gray overcoat approached. Suddenly she had a flashback—a huge room with harsh lights, the shame of walking naked past this man wearing a blue uniform and a cap with its skull and crossbones insignia. She pictured her frail older sister, Betsie, with parchment-like skin, who had suffered such inhumane treatment from this man and his cohorts.

“You mentioned Ravensbruck in your talk,” he said. “I was a guard there. But I have since become a Christian. I know that God has forgiven me for the cruel things I did there, but I would like to hear it from you as well. Fraulein, will you forgive me?” he asked as he extended his hand.

Corrie knew she had to do it. “The message that God forgives has a prior condition: that we forgive those who have injured us. Forgiveness is not a feeling; it is a choice, an act of the will. So I asked God to help me really do that,” Corrie told her audience the day I heard her speak.

“I wrestled with the most difficult thing I had ever had to do. I thought I had fully forgiven my enemies until I was face-to-face with a guard whom I recognized,” she continued. When she finally stretched out her hand to shake his, she said, “It felt like a current racing down my arm. And then this healing warmth seemed to flood my whole being as I held his hand.”

“I forgive you, brother, with all my heart,” she told him. The former guard and the former prisoner grasped hands.

Fran says the key lesson that Corrie taught her is: “God has a hiding place for those who seek Him.” That theme permeates Corrie ten Boom’s numerous books and messages.

— V —

About the Author

Quin Moore Sherrer, a Northwest Florida native and FSU journalism graduate, has written or co-authored 28 books. She was a reporter for the Ft.Walton Playgound News and the Titusville (Florida) Star Advocate newspapers.

Quin Moore Sherrer, P.O. Box 1661, Niceville, FL 32588 850-729-7514

Some of Corrie’s books:

Amazing Love

Common Sense Not Needed

Not Good If Detached

Marching Orders for the End Battle

Plenty for Everyone

In My Father’s House

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE