vie-magazine-connemara-life-marconi-project-hero

Aerial view of what is now Derrygimlagh Signature Discovery Point from November 2011

Guglielmo Marconi

Connecting the World

By Amanda Crowley | Photography courtesy of the Marconi Project

History allows us to look back and appreciate the enormous strides achieved by pioneers in science and technology. Sadly, stories are often forgotten, replaced by the next great advance or discovery, or buried in a bog of compounding layers built upon that first spark of genius. But recently, historians in western Ireland have come together to unearth the past and share the accomplishments of inventor Guglielmo Marconi. Long before Ireland was known as the European Silicon Valley, Connemara helped lay the groundwork for the mobile phone that we can’t seem to live without.

With the help of the Connemara Chamber of Commerce, the Clifden Chamber of Commerce, the Galway County Council, and Fáilte Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way, a small team has begun to memorialise Marconi and his tenacious spirit that connected two continents by way of radio telegraphy. The team includes Shane Joyce, noted radio archaeologist; historian Michael Gibbons, one of Ireland’s leading field archaeologists; and Christopher Shannon, former president of the Clifden Chamber of Commerce.

Guglielmo Marconi

Marconi was the son of Italian country gentleman Giuseppe Marconi and Annie Jameson, of the Jameson Irish Whiskey family. He was born 25 April 1874 in Bologna, Italy, and it was there he began his work on radio and wireless communication as a young man, studying the works of Hertz, Maxwell, and others whose works challenged his imagination. Marconi later moved to England to further his research, gaining legal and scientific recognition and even winning a shared Nobel Prize in Physics in 1909, sixteen years after he began experimenting with electromagnetic waves.

Location, Location, Location

Marconi’s original telegraph stations were built in Cornwall, England, and Cape Cod, Massachusetts, but when the distance proved too great, he was forced to reconsider locations. A grant from the Canadian government, equating to about €1 million today, allowed him to construct a station in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. Knowing Cornwall would still be too far, Marconi ventured to the wild Irish west coast, finding both the ideal distance and conditions in Derrygimlagh near the town of Clifden. The station began operating in April 1907.

- Carolyn Lloyd and Alan Joyce re-enact research being done at the Letterfrack station, April 2014.

- Engineer B. J. Witt and local workman Peter Guy conduct research near mast No. 3 Currywongaun Hill.

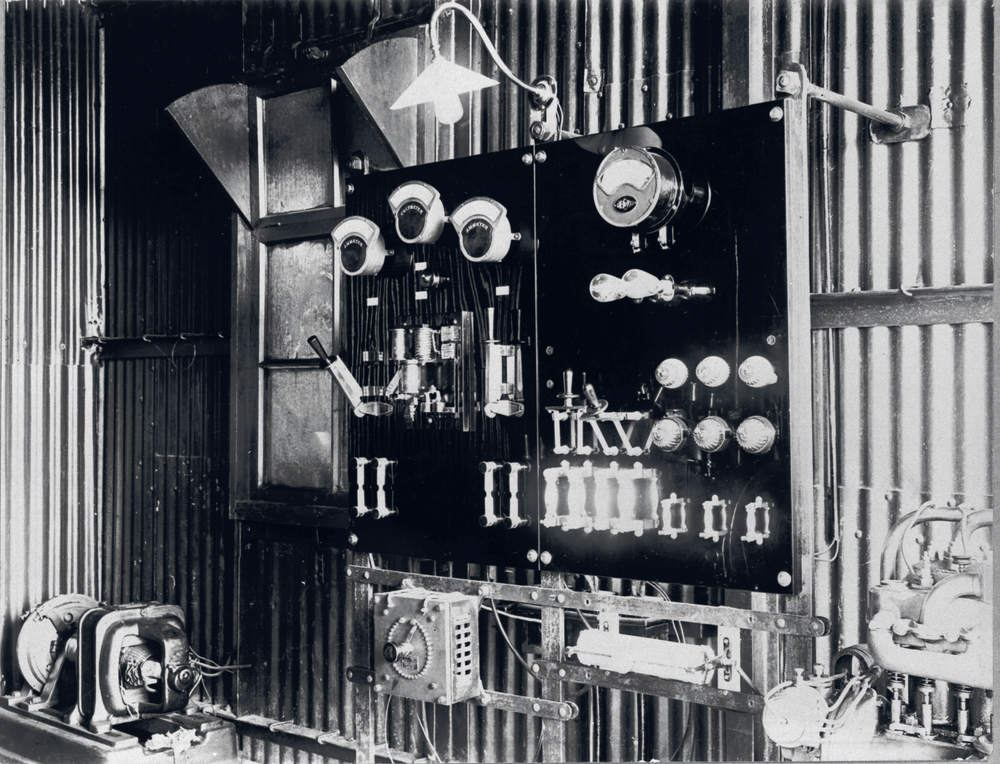

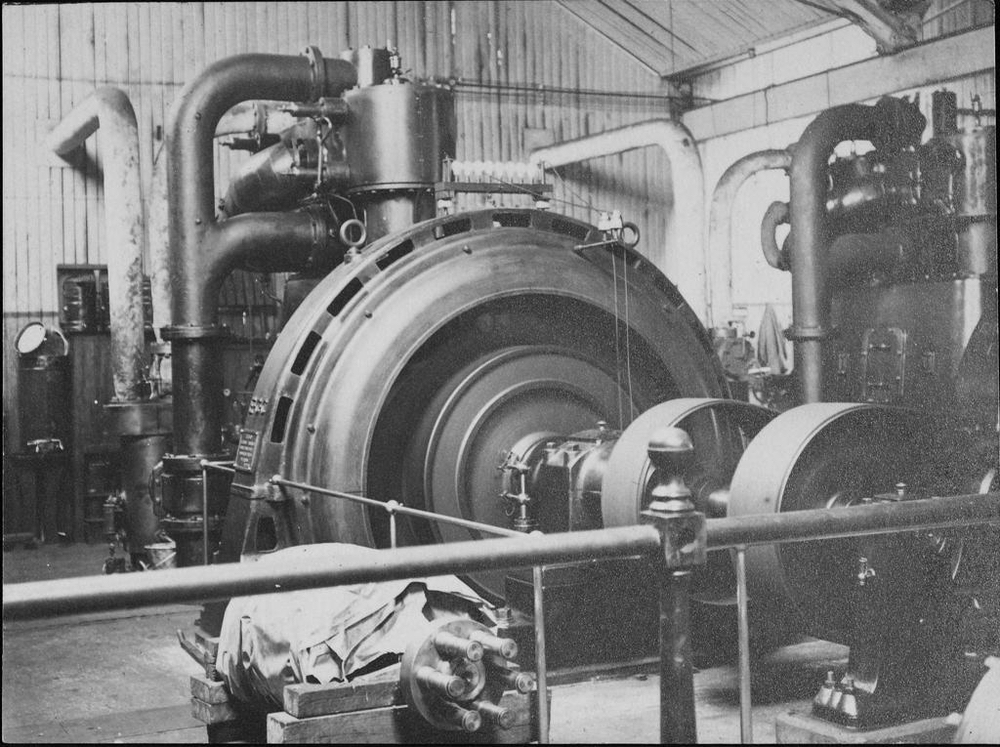

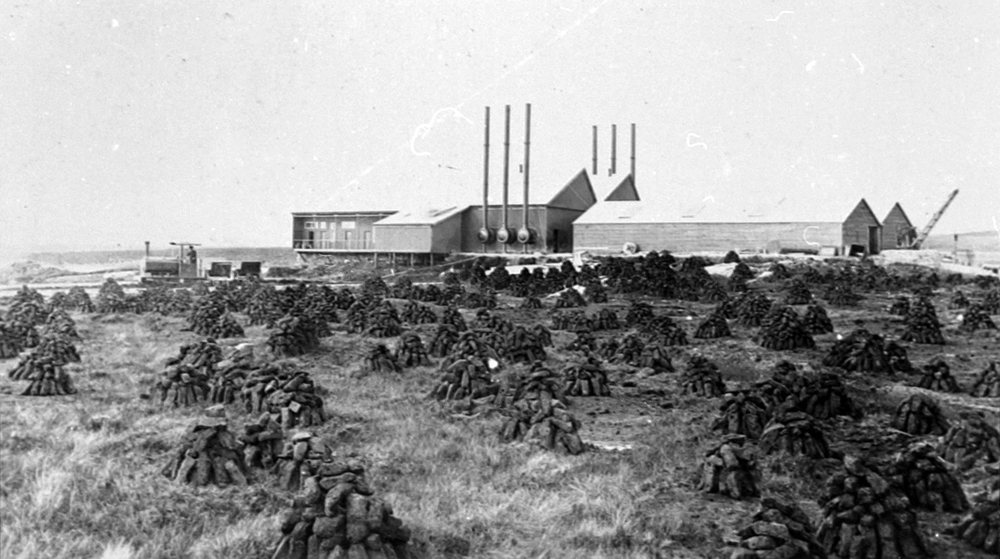

‘Connemara is not an area most people would associate with technology,’ Joyce says. ‘The climate is considered wild, but its location and distance to North America, in addition to the unobstructed boglands, was ideal for sending and receiving messages.’ When looking at the site today, it’s easy to imagine what Marconi saw: empty boglands sprawling for miles and the spirit of determination embedded in the earth. He could envision a massive operation with a condenser house, tall transmitter towers, workers’ quarters, generators, peat boilers, and a small railway.

On the morning of 15 October 15 1907, only the tapping of a message by the duty operator could be heard in the Irish station. At exactly 11.30 a.m., a message was transmitted to the New York Times. Its successful reception in Glace Bay launched the commercial signalling between continents and officially opened the Clifden Marconi Station. Shortly after, a congratulatory message was sent from Glace Bay confirming receipt. Ten thousand words were transmitted across the Atlantic that first day, thanks to Marconi’s genius and tenacity and the hard-working Irishmen powering the station.

Ruins from the once-bustling Clifden Marconi Station

Marconi’s telegraph brought not only excitement but also new employment to Connemara, as local men who were skilled at cutting, stacking, and drying turf from nearby bogs provided a ready and eager workforce to harvest fuel for the station. (Turf fires have provided heat in Connemara for centuries, and anyone who has visited will recognise the welcoming scent immediately.) Men were also employed to build the Marconi Light Railway for transporting turf from the bog to the station’s furnaces.

[double_column_left]

[/double_column_right]Marconi’s telegraph brought not only excitement but also new employment to Connemara, as local men who were skilled at cutting, stacking, and drying turf from nearby bogs provided a ready and eager workforce to harvest fuel for the station.

Advancing Technology

Ireland inspired Marconi, and he seized the opportunity to grow while in Connemara. In 1911, Marconi opened a second radio station seven miles away in the village of Letterfrack, installing a separate directional antenna system. Much like a walkie-talkie, messages would be sent in one direction for a number of hours, and then stopped to receive messages for a few hours, allowing messages to be sent to and received from different directions. Two antennas were installed: one aligned toward North America, the second facing Clifden. With the help of engineers R. N. Vyvyan and C. S. Franklin, Marconi discovered how to dissipate interference from the local radio signals, leaving the transatlantic lines open. Financial restraints caused the Letterfrack station to close in 1917, but the work done there was monumental.

While Marconi’s invention sparked intrigue and garnered popular interest, it also proved essential in nautical life. Jack Phillips, senior radio operator aboard the RMS Titanic, had worked at the Marconi station in Derrygimlagh before taking up assignment on the fateful ship. Twenty-six-year-old Phillips lost his life on the Titanic after sending numerous distress messages and refusing to leave his post until the power went out. Phillips sent the SOS and CQD messages still commonly used by Marconi operators, signifying a general call to all ships requesting immediate assistance. Survivors of the tragic event of 15 April 1912 owe their lives to Phillips’s unwavering dedication and to Marconi’s invention.

- Sheep graze on the Derrygimlagh boglands.

- The Derrygimlagh landscape offers breathtaking views spotted with tiny lakes and peat bogs.

For all his success, Marconi also faced setbacks. Despite the fact that both his mother and his first wife were Irish, he was perceived as owning and operating an English company. During the Irish War of Independence, rebels cut down telegraph lines used for transmitting information for fear the company would contact British troops and destroyed Marconi’s remaining station in July of 1922.

Marconi’s work in Connemara forever changed the way the world communicated, laying the groundwork for the massive communication networks of today. To honor his legacy, wireless stations worldwide observed a two-minute radio silence upon Marconi’s death in Rome on 20 July 1937.

Alcock and Brown

As Marconi was changing transatlantic communication, Alcock and Brown were cementing their place in transatlantic transportation. Pilot Captain John ‘Jack’ Alcock heard that the Daily Mail was offering a £10,000 prize to the first aviator to cross the Atlantic in less than seventy-two hours. He employed the help of navigator Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown for the journey. The pair travelled to Newfoundland along with a number of other teams, hurriedly inspected their Vickers Vimy bomber plane, and with the aircraft’s bomb bay full of extra fuel, took off at 4.12 p.m. GMT on 14 June 1919. The men endured freezing temperatures, ice, fog, and even a broken airspeed indicator during the journey.

Vanishing Point at the old Derrygimlagh station power house.

The sea fog broke as the plane approached the Irish coast, and Brown spotted a railway below. He scribbled a note telling Alcock to follow it. Fearing their competition had already touched down, Alcock and Brown decided to land in what they believed was an open field; however, it was actually the Derrygimlagh bog, and once the plane’s wheels touched down, they began sinking. On the morning of 15 June 1919, despite their unorthodox landing, Alcock and Brown became the first people to fly continuously across the Atlantic.

Marconi station workers, who had tried to wave the pilots away from the bog, ran to their aid. ‘Yesterday we were in America,’ Alcock told them. When the station workers spotted a small bag of mail onboard, the magnitude of the historic event began to set in. With great honor, they sent the message from the Derrygimlagh Marconi Station stating, ‘Vickers Vimy aircraft landed Clifden 8.40 GMT from Saint John’s. Alcock.’ Alcock and Brown remained in Clifden only for the day, but landing at Marconi’s station in Derrygimlagh allowed the news to spread quickly and globally, adding another technological milestone to Connemara history.

Marconi’s work in Connemara forever changed the way the world communicated, laying the groundwork for the massive communication networks of today.

- Engineers observe a total solar eclipse on 17 April 1912 from the Clifden Marconi Station.

- Marconi wireless technology used to transmit and receive messages

The Derrygimlagh Signature Discovery Point

The recent Derrygimlagh Signature Discovery Point project began much like Marconi’s, with a comprehensive survey of the site. Archaeological digs were conducted, led by Gibbons. Joyce claims the ‘timing was fortunate for the project’ as grant money was available, but without passion, it would never have begun. Visitors are able to enjoy a four-and-a-half-kilometre boardwalk and new paths featuring breathtaking views of boglands, the nearby lake, and the remnants of the historic site of Marconi’s first station in Connemara. Designers, keeping the Irish weather in mind, planned for covers over three of the six information stations along the tour. These stations will display historic images and information in both English and Irish.

The site also features several ‘historioscopes’ designed by Irish artists Anne Cleary and Denis Connolly. The devices are like periscopes; viewers look through and see images of the Marconi station condenser house, the railway, and the workers’ bungalows where they originally stood—a creative way to recreate the historic landscape without changing the current terrain. A ‘panoramascope’ accompanies the historioscopes, showing the crash landing of Alcock and Brown’s plane.

The Marconi Company brought welcome employment and excitement to the town of Clifden. At the time, Clifden’s population was 900.

Archaeological expeditions are ongoing, and additional discoveries have been made on-site, including the uncovering of the railway turntable used for bringing turf to the station. The team hopes the site can remain an archaeological school where students can learn about the history of Marconi and the landscape he chose for the station.

The Derrygimlagh Signature Discovery Point officially opened in May 2016. Going forward, the chambers will continue to raise funds and support this landmark, with plans to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of Alcock and Brown’s landing in 2019.

Marconi, Alcock, and Brown dared to dream, and their achievements continue to inspire innovators and travellers today. If your mobile phone vibrates in your pocket while you walk through Derrygimlagh, thank those who paved the way and helped make that technology possible.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE