vie-magazine-farm-to-table

Growing and Eating Local

Farm-to-Table Movement Is Making Its Way in America

By Sallie W. Boyles

The farm-to-table (or if you live by the ocean, the sea-to-table) idea is hardly revolutionary. The practice has been around since humans learned to plant and grow crops, catch fish, and raise domesticated herds for meat and dairy. But along with the Industrial Revolution came the appeal of mass farming and production. With a desire for convenience and the need for a long shelf life, processed foods and frozen dinners became staples of nearly every modern household.

In recent years, however, consumerism has made a breakthrough. At last, by turning away from unhealthy options, people are returning to the natural goodness of Mother Earth. Farmers’ markets, such as the one that takes place every Saturday morning in the town square of the New-Urbanist oasis of Seaside, Florida, have popped up in cities across the country. Vendors peddle fresh fruits and vegetables, and local chefs, grocers, and regular Joes alike choose the goodies they’ll take directly to the kitchen to whip up tasty, healthy meals for their families or patrons.

While investigating the farmers, markets, and retailers that are driving the farm-to-table movement in Northwest Florida, VIE foraged for some of the freshest and, arguably, the healthiest fruits of the land—and, of course, the sea. We’re delighted to share a taste of what we gathered from Apalachicola oysters, Dragonfly Fields, Mac Farms, Twin Oaks Farm, and For the Health of It.

Yes, we repeatedly heard that local and fresh go hand in hand, but we also gained some intriguing insights about today’s farming methods, along with a better understanding of how this back-to-basics (but certainly not backward) approach fuels economic growth and healthy relationships within communities. It’s no wonder that Americans are now returning to food production and distribution strategies that, from the beginning, were nutritionally practical.

Locally Grown Greens

By L. Jordan Swanson | Photography by Marla & Shane Photographers

As early as 1627, a publication by Francis Bacon described how to grow terrestrial plants without soil. Three centuries later, a University of California professor coined the name hydroponics using a combination of the Greek terms hydro for “water” and ponos for “labor.” Thanks to intensive research over the past few decades by prominent institutions like NASA and even Walt Disney World’s Epcot, the hydroponic system of farming is now a viable method for today’s serious growers.

When Jen and Andy McAlexander first began cultivating herbs and vegetables using a nutrient solution without soil, their pursuit was just a hobby. As production flourished, however, their pastime turned into a full-time enterprise, entailing the management of three thousand pots between two farm locations in Walton County, Florida. “We’ve had Mac Farms going and have been selling to chefs for five years,” says Jen, “but we started the LLC and made it a real business in 2009.”

Jen McAlexander, and her husband Andy, officially established their business Mac Farms in Walton County in 2009.

“We got into potted farming when we first moved here and realized you can’t really garden in the sandy soil,” Jen says. A friend introduced the McAlexanders to the system and later sold it to them when he moved away. “We just started adding plants in our own yard,” she says, explaining that they expanded their farm to the property they own a short distance down the road. Approximately one third of the produce pots are grown on the smaller farm, which was started first, and the second location, now the main farm, has the rest. Each of the three thousand pots typically holds four plants.

More than a fascination, the hydroponic system presents a superior option for growers dealing with space restrictions or unfavorable soil conditions. Mac Farms uses a drip irrigation system called Verti-Gro that Jen and Andy purchased but assembled themselves. The method feeds nutrients to the plants, which are contained in pots filled with coconut coir fiber and perlite.

Critter control is another benefit of hydroponic farming. Since pests tend to live in the soil, keeping plants out of the ground eliminates the need for heavy pesticides. When necessary, Jen applies biologicals—all-organic natural oils and sprays for pest control. For that reason, Mac Farms is not certified organic, but Jen refers to her process as natural. Both farms are also open-air operations, although shade covers are used when necessary during the summer to protect against the sun’s intense rays.

Mac Farms provides fresh herbs and vegetables to local chefs.

The main farm cultivates arugula, kale, mixed greens, and fingerling potatoes. Heirloom tomatoes are a major crop in spring and summer. At the smaller farm, Jen grows spinach and, at times, micro greens. Overall, arugula and heirloom tomatoes are her biggest sellers. She makes a point of mentioning the tomatoes, which have a robust flavor and come in a variety of colors with different acidity levels.

Of everything produced, not much goes to waste at Mac Farms. Instead of allowing the runoff from the irrigation system to fall to the ground, the bottom pots catch the water that, in turn, cultivates the growth of fennel, green onions, and chard. Likewise, when greens get too mature, Jen cuts and feeds them to her thirty-nine chickens used for egg laying. She has a wide variety of chicken breeds on the farm, including Ameraucana, Buff Orpington, Wyandotte, and Black Copper Marans. “We’re hoping to have enough eggs in the spring to start delivering to a few of the chefs,” Jen says.

Arugula is one of the most popular crops that Jen sells to chefs on 30-A.

Primarily, Mac Farms sells to chefs. “We knew a group of chefs locally and talked to them about buying local greens, if they could,” Jen says. Noting that they were enthusiastic, she explains, “We focused on providing for them.” Mac Farms regularly supplies the area’s signature restaurants, like Edward’s, Bud & Alley’s, and Stinky’s Fish Camp. “If a chef wants something special, I’ll definitely try to do it,” says Jen, who one day hopes to have enough produce to provide for the local farmers’ market.

“Our big thing is just keeping it local—trying to boost our own economy,” she says, “and to decrease the gas used to deliver and distribute. It takes me a five-minute car ride and I’m there. I cut and deliver everything the same day, so it’s very fresh. Also, if the chefs need anything last minute, I can just run out here and cut it and quickly get it to them within an hour.”

Mac Farms also sells arugula, spring mix, heirloom tomatoes, and olive oil (sourced from California) online at macfarmsfl.com based upon growing conditions. Local orders are delivered within South Walton County on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays.

Some measure of growth is always on Jen’s mind. “Future expansion would hopefully include a larger, enclosed space,” she says. The option would enable her to control temperatures to grow spring and summer vegetables—primarily heirloom tomatoes, but also greens—year-round.

Readers can learn more about Mac Farms on their website at macfarmsfl.com or on Facebook.

Health in the Neighborhood

Story and photography by L. Jordan Swanson

When people hear the words health food, some might picture blueberries, turkey bacon, and wheat toast for breakfast, and maybe chicken, broccoli, and mixed greens for dinner. Whatever they envision, one thing is certain: most Americans could incorporate a little more health food into their diets. Although vegetables and lean meats are good for the body, few people eat them in their healthiest forms. Many supermarket products, for instance, are grown with the assistance of pesticides and hormones, and then later processed with synthetic additives. Consequently, consumers with the best intentions to eat well frequently make misguided choices.

For The Health of It owners, Ed Barry and Rachel Morgan, offer the community organic and gluten-free products for healthy living.

To learn a thing or two about health and eating well, VIE consulted Ed Barry and Rachel Morgan, owners of For the Health of It in Santa Rosa Beach, Florida. “We started the store years ago with the idea of bringing fresh, organic, healthy choices to Walton County and 30-A, really out of our own personal need,” says Ed. “We were living a clean, healthy lifestyle, and we were used to eating organic foods. There wasn’t anything like this around, and we were tired of having to drive to Pensacola or Tallahassee to get our food.”

The store’s most popular products include certified organic produce, grass-fed meats, and an extensive line of gluten-free foods, which especially benefits those with allergies. For the Health of It also offers an assortment of honeys, nutritional supplements, custom-ordered juices and smoothies from fresh fruits and vegetables, and more.

With a greater focus on the farm-to-table movement—working with as much local and regional food as possible to avoid shipping and other environmental concerns—area health food stores can be optimal sources for fresh goods. “It’s a great movement to make fresh, clean food available on an everyday basis,” says Ed.

To support the effort, For the Health of It buys from several local and regional food growers, including Dragonfly Fields, Whittaker Gardens, and Hastings Farm. “We also have many people come to us with food from their garden,” says Rachel, “but we are very particular about what we purchase. We have many cancer patients and others who use the foods for their healing modalities, so we have to make sure we know how the foods are grown.”

“Working with local vendors is about the quality and the freshness of products,” says store manager Peter Lovecchio, known affectionately to Ed and Rachel as Produce Pete. “It also saves on fuel by not having to transport products long distances across the country.” Peter has been working in produce for about thirty years, twelve of which have been spent at For the Health of It. “Sustainable agriculture is about letting the earth take care of us instead of vice versa,” he adds. In other words, sustainable agriculture allows foods to grow naturally instead of relying on artificial enhancements.

Besides selling organic produce and specialty items, For the Health of It also provides massage therapy. Opening eighteen years ago with the grocery store, the massage clinic—featuring licensed therapists and four treatment rooms—was the area’s first. Further promoting a better sense of individual wellness and health, both inside and out, massage therapy, much like healthy eating, can leave the body feeling rejuvenated.

With some of their customers commuting two and three hours just to get their health food fix, the business has a tremendous following. Ed and Rachel are grateful to those who make such an effort yet maintain that they owe the bulk of their success to the support of the South Walton community. “It’s all about learning from them, providing those products for them, being on top of the local health trends, and being open-minded,” Rachel says. As evidenced by the way one shopper after another delightedly greets Ed and Rachel as if they were old friends upon entering For the Health of It, the store’s loyal patrons genuinely appreciate the owners’ commitment to serving them. The customer base, in turn, continues to expand.

“Our target market used to be people who were looking for clean alternatives to regular, conventionally grown foods,” says Ed. “Now, they understand what’s going on in the food industry—that growth hormones are added to meats and antibiotics are found in milk now. As people are becoming more educated, our clientele has grown.”

Rachel adds that people make the transition to clean eating for many different reasons. “It might be a mom who has a kid with behavioral issues or food allergies,” she says. “Or, it might be that they heard something on TV.”

It’s all about learning from them, providing those products for them, being on top of the local health trends, and being open-minded.

“We are currently in the process of rebranding right now, using the concept of ‘Your Neighborhood Organic Grocery,’” said Ed. “We look at our store as our child. At eighteen, it’s an adult now and going off to college,” he jokes. “We need to spruce it up a little bit.” Working with David DeGregorio at the Central Idea Agency, a local agency in Santa Rosa Beach, the owners hope to unveil the new look by April 8, the official eighteenth anniversary. “It’s a mix of old-school grocer and a modern feel,” Ed describes.

No matter how different the store looks, the enduring qualities of the business will stay the same. “We’ll continue to listen to our customers with the understanding that they have just as much knowledge about what we’re doing as we do,” says Ed, “and we always try to provide the best quality service in a friendly atmosphere.”

For the Health of It, located at 2217 West County Highway 30-A in Santa Rosa Beach, is open for business Monday through Saturday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. For more information, readers can contact the store at (850) 267-0558 or visit their website at shopforthehealthofit.com.

Taste the Difference

Story and photography by L. Jordan Swanson

For Renee Savary, taking care of more than two hundred farm animals is a full-time job that begins with a cup of coffee and ends with getting the last chicken into its coop. Savary is the owner of Twin Oaks Farm in Bonifay, Florida, a ninety-four-acre spread that’s USDA Certified Organic and 100 percent soy-free.

That acreage is used mainly for raising chickens and ducks, but it is part of a larger mission to promote environmentally friendly practices through the organic cultivation of nongenetically modified vegetables and fruits, the production of all-natural goods, and the breeding of heritage livestock and poultry in an effort to support their conservation. And except for a twice-weekly helper, Savary tackles that agenda alone.

Savary was inspired to start her own farm four years ago, when processed foods began affecting her health. A native of Switzerland who moved to Miami Beach two decades ago, she was raised on farmers’ market food. “Not because it was fancy,” she clarifies, “but just because that’s what you did.”

Renee Savary started her business Twin Oaks Farm four and a half years ago.

Within a few years of her transatlantic move, however, she became really sick and couldn’t figure out why. When she finally realized it was because of the food she was consuming, Savary turned to organic foods. Like most people, she noticed the price was a bit steeper than for nonorganic foods, and, thanks to her new career, she understands it’s simply because food costs more to produce organically. For example, the feed she gives her chickens costs three times more than regular chicken feed because it’s certified organic and soy-free. “I’m very proud of the quality produced here,” she says. “I don’t cut corners, and you can taste the difference. It’s what I call real food.”

Savary’s list of animals and their duties is both impressive and entertaining. About 150 chickens and fifty ducks of all ages and stages of egg laying roam the farm (it takes six months before chicks lay their first eggs). Among her assortment are Colored Range chickens for meat and Rhode Island Reds for eggs. Her chickens are protective of their farmland and coops, often growling at unsuspecting visitors, but when they need protection from the real threats—dogs, coyotes, foxes, and other predators—Savary’s seven donkeys act as security guards. Two of the donkeys are also learning how to pull carts full of fencing, feed, trash, and anything else that needs to be moved around the farm.

The small herd of Gulf Coast sheep relaxing in the pasture is good for meat and wool. Twelve geese that hang out in one of the three ponds are egg layers—and serve as an effective alarm system when anything out of the ordinary occurs, including the presence of intruders. Last but not least are Savary’s eight cats, which keep mice away from the chicken feed, and the bees she raises for honey.

When it’s time to distribute the wealth that comes from her farm animals, Savary welcomes customers who want to buy directly from the farm. She also sets up shop at Seaside Farmers Market—the only farmers’ market she frequents. “For me, it’s important to be organic, but it’s also very important to keep the local label,” she says.

Savary has been a Saturday morning fixture at the market since 2008, offering eggs, chicken, and seasonal treats. “Depending on the season, I have duck meat, turkey, and a whole line of preserves. Besides the jams and the jellies, I also have tomato sauce and what I call a ‘meal in a jar.’ I do chicken in curry sauce and chicken in mushroom cream sauce—things that people can just warm up and put over rice.”

Though she has a long list of goodies, eggs are Savary’s main staple. She collects them twice a day in the winter and three times a day in the summer. “Every day is an Easter egg hunt,” she laughs.

Another popular product is her preserves, which Savary makes in the farm’s commercial kitchen. Her preserves are prepared with fresh, organic fruits either straight from her farm or purchased from a small local grower. Unlike what’s on grocery store shelves, Savary’s preserves are made without pectin, citric acid, ascorbic acid, dyes or fillers. And, of course, she only uses local products such as blueberries, strawberries, peaches, lemons, oranges, and mandarins.

Her farm and the products that come from it are more than a way to make a living; Savary is trying to make a real difference in people’s lives by encouraging them to get closer to the foods they eat. “Let’s face it—what you find in a supermarket today is a pretty scary thing,” she says.

Perhaps because of her own experience, she’s a firm believer that most of the health issues we face in this country could be resolved with a change in diet. Noting that food choices can be life-or-death important, she cringes at the apparent apathy she sees. “People know more about the technology of the latest gadget than the food they put in their mouths,” she marvels.

It may cost a little more to eat better food, but the payoff, as Savary knows, is priceless.

To learn more about Twin Oaks Farm, visit www.twinoaksfarm.net or find it on Facebook at facebook.com/TwinOaksFarm.

Healthy earth = Healthy Earth

Food for Thought from Dragonfly Fields

BY Jordan Staggs | PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARLA & SHANE PHOTOGRAPHERS

Organic. Pesticide-free. All natural.

It’s easy to read these words on packages in the supermarket and think, “This is healthy.” The sad truth: Many products on the shelves have traveled hundreds, if not thousands, of miles by airplane, truck, or ship to get there. At times, they are not only shipped weeks before arriving, but some foods that are vulnerable to spoiling are also shipped in substandard (as in too warm) conditions.

How can you ensure that the products you’re buying are the freshest, healthiest options out there? Venture into the magical land of small farming and fresh markets, where you’ll find answers that are as plain as the tomatoes in the basket. In fact, Charles Bush and his wife, Shueh-Mei Pong, owners of Dragonfly Fields, a small seventeen-acre farm in DeFuniak Springs, Florida, will tell you that freshness starts the way anything else does—from the ground up.

“When we do something, it’s natural,” Charles says. “There are many labels you can put on it, but our main concern is feeding the soil and maintaining freshness that way.” Healthy soil equals healthy plants. The idea is simple enough, but plenty of work goes into making sure the earth is in the best condition for growing produce. “It means putting organic material and trace minerals back into the soil, composting, and doing soil tests to see what needs to be added, like lime, boron, or potassium sulfate.”

No matter the requirements, the soil and produce at Dragonfly Fields are treated with tender loving care. The owners cultivate only one or two acres of the farm at a time, and they use only natural or organically approved fertilizers and pesticides when needed. “We don’t use any conventional fertilizers. Everything we do is natural,” Charles says. “That makes a big difference in our food, and you can tell it in the flavor, the richness, the texture, and even the appearance.” Looks are important. “Everything should look good along with tasting good and holding up well.”

The owners cultivate only one or two acres of the farm at a time, and they use only natural or organically approved fertilizers and pesticides when needed. “We don’t use any conventional fertilizers. Everything we do is natural,” Charles says.

Consumers appreciate quality, which is why Dragonfly has become a staple at the Seaside Farmers Market. Although Charles and Shueh-Mei must travel about forty miles from the farm to participate in the event on Saturdays, they say the trek is worthwhile. The biggest advantage, according to Charles, is allowing customers to put a face on the Dragonfly name. Buyers further learn the origins of their food. “They know what the source is,” he says, “and if they have a problem, they can come to us directly.”

Over the past several years, the farmers market has contributed to building a healthier community. “We work with six local restaurants and chefs,” Charles explains. “It’s to their advantage to buy local produce because it’s going to be fresh and flavorful; they don’t need to do a lot or create a complicated sauce to go with it. They are creative with recipes, but tend to keep them fairly simple.” With produce straight from the farm, a quick rinse is often all the preparation needed. “We’ll sometimes be out picking and eating right in the garden,” he says, “so you know you’re getting a wholesome, fresh product.”

By making locally grown food available to the community, the farmers market, restaurants, and stores, such as For the Health of It, are also more intimately connected to one another and consumers. “They might buy our tomatoes at the market on Saturday, so when diners then see them on the menu at Fish Out of Water, they’ll know where their food came from,” Charles says. “Or if they’re looking for something at the market and we just sent out a big shipment, we can send consumers to the restaurants or the health food store. I think everybody is interconnected. This is something being reborn from how it used to be,” Charles says, referring to the rebirth of farmers markets and the farm-to-table movement.

Charles and Shueh-Mei began farming with a restaurant background. Both traveled to Grayton Beach in the eighties to work at Paradise Café, where they met, and later opened Basmati’s Asian Cuisine in Blue Mountain Beach. Their experience is an asset when dealing with chefs and consumers. “We know what they’re looking for and what fits into their menu,” Charles says, “so we can talk to people about how to prepare things and what goes together.”

As much as they love farming and serving up recipes to accompany their produce, Charles and Shueh-Mei also look forward to traveling and visiting restaurants. Although keeping abreast of cuisine and farming trends is part of the job, the two certainly enjoy the tasty perks experienced along the way. “That’s our business and we like doing it,” Charles says with a laugh.

Above all, they feel good about the arugula, strawberries, and tomatoes grown at Dragonfly Fields that land in the hands and mouths of those who desire the healthiest, freshest foods. “We’re trying to do the right thing,” says Charles, “and the way we farm seems like a natural fit for the way people want to eat.”

Dragonfly Fields

1600 County Hwy. 192

DeFuniak Springs, FL 32433

E-mail: dragonfly1600@embarqmail.com

The Champagne of Oysters

BY Melanie A. Cissone | PHOTOGRAPHY BY Mark Wallheiser

“We’re … on our … way to AP-A-LA-CHI-COLA … F-L-A.”

That’s what Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters sang in the 1947 film Road to Rio, costarring Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour. Part owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team at the time, Crosby asked one of the players, Jimmy Bloodworth, where he was from. Amused by the name Apalachicola, Crosby committed to using it in a song. While the catchy tune may have been entertaining, the hidden treasures of Apalachicola Bay—its oysters—were never even mentioned. Perhaps it was better that the mildly salty, plump bivalves from this rich estuary were kept under wraps back then; as it turns out, they are some of the most sought after in the country.

What’s a bivalve, you ask?

For those who normally mistake bivalves for brachiopods—naturally confusing, of course, because of their similar lifestyles and sizes—bivalves are marine and freshwater mollusks with compressed bodies enclosed by a two-part hinged shell. Clams, oysters, mussels, and scallops (the swimmers in the bunch) fall into the bivalve category. The majority of bivalves have neither heads nor radulae (ribbon-like structures used for feeding) and therefore are filter feeders. Most bivalves hang out under the sediment level of a seabed, usually in the general vicinity of where they were born, and away from predators of the nonhuman variety.

Oysters filter water by drawing it over their gills, trapping the plankton and other particles in the mucus of the gill, which they eat, digest, and expel. An individual oyster can filter up to one and a half gallons of water per hour, and thriving oyster beds are responsible for filtering excess nutrients, like unwanted algae, and mitigating pollutants from massive volumes of the waters where they live. Oyster reefs provide an extraordinary and unique habitat for many other marine species. Basically, oysters keep the neighborhood clean and tidy. You asked, didn’t you?

In Apalachicola and Eastpoint, generations of oystermen, or “tongers” as they are sometimes called, continue to harvest most of the oysters by hand, something that is unique to Apalachicola Bay compared to other parts of the country, where oysters are mechanically dredged. The 19,300-square-mile area that drains into the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin near the town of Apalachicola winds its way through north Florida along the Apalachicola River, the most bio-diverse river in the United States. The basin itself is between six and nine feet deep at low tide, and wild oysters there must be at least three inches long to be legally harvested. Achieving that size takes two to three years. “Oystering” is generational and approximately a thousand of the 11,500 residents of Franklin County are employed by the multimillion-dollar industry, which provides 90 percent of Florida’s oysters and 10 percent of the supply nationwide.

For enjoyable and informational reading on the subject of oysters, A Geography of Oysters is essentially a guided tour of North American oysters. The Los Angeles Times describes it as follows: “There may be no more pleasurable food than a raw oyster, there almost certainly is no better guide.”

Author Rowan Jacobsen takes his readers on a journey through the varieties, harvesting, culling, and eating (raw or cooked) of North American oysters. On his corresponding website (oysterguide.com), the James Beard Award–winning author writes about food, notably oysters; the environment; and the intersection of the two. Jacobsen peppers the book and blog with historical perspective, touches on long-held myths about oysters, theorizes on the reasons why oysters get lumped into the category of aphrodisiac, and offers personal experiences and recipes collected while researching the book.

In a recent interview, Jacobsen said, “I think Apalachicola oysters are wonderful.”

Last April, after a day of oyster tonging with third-generation oysterman Kendall Schoelles, Jacobsen wrote on his blog, “It’s blissful to be out there, no other boats around, culling oysters, whacking your thumb, smelling the wind and water, listening to the catfish sloshing around the surface, and popping open the occasional oyster and eating it on the spot. (Best I’ve ever had.)”

If Jacobsen puts anything on his oysters at all, he prefers citrus to vinegar in making his mignonette (a condiment for oysters usually made with vinegar, shallots, and pepper) and stresses how essential the zest of the citrus is as an ingredient. He writes in Geography, “… the acid will counteract the saltiness … so citrus and mignonettes help to balance excessively briny oysters. They also enliven a dull oyster … I prefer nothing on the best oysters.”

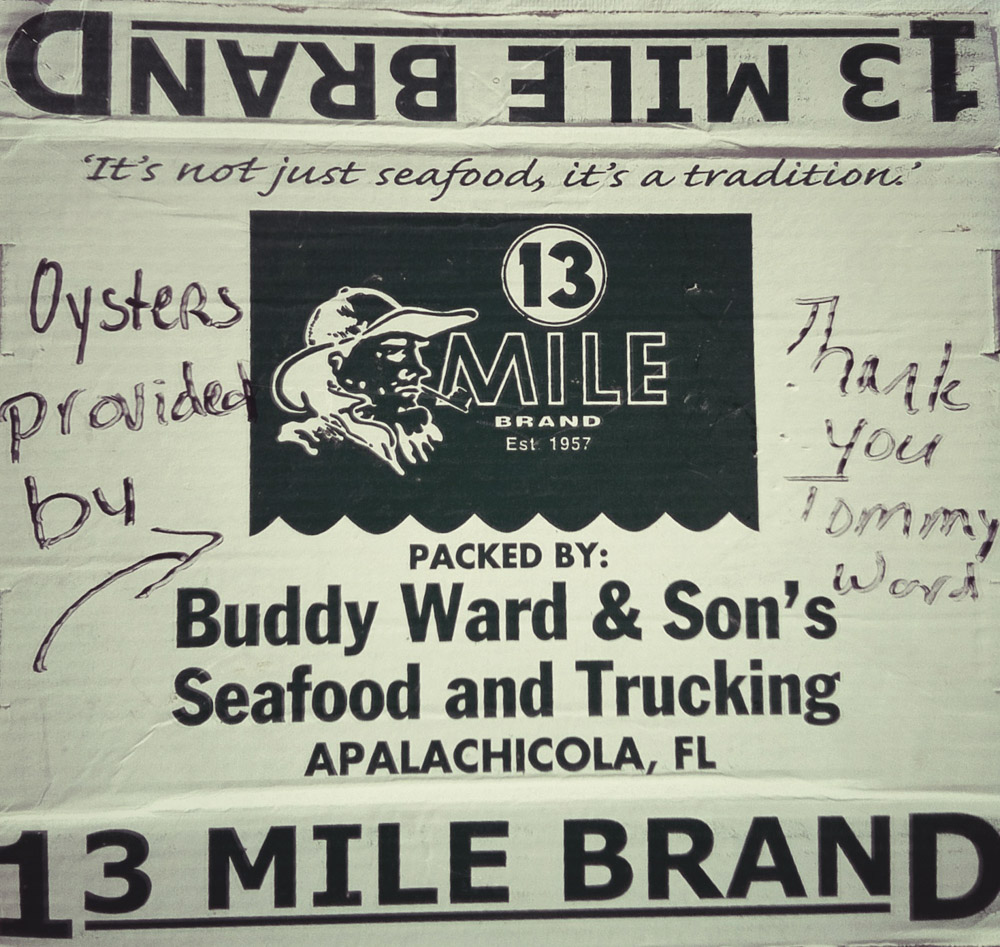

Phillip McDonald, owner and chef of Table Five – Personal Chef and Catering, uses oysters from 13 Mile Oyster Company, a part of Buddy Ward & Sons Seafood & Trucking, Inc. The oysters, referred to locally as “13 Mile Brand,” are harvested by the owners, brothers Tommy and Walter “Dakie” Ward, in oyster beds thirteen miles west of Apalachicola. 13 Mile Brand owns more than half of the leased beds in the bay at a time when leases are no longer being given. Chef McDonald said, “For the sea-and-farm-to-table dinner for VIE, I was inspired to create a seasonal menu from what we grow, raise, and harvest locally and by what the Gulf offers. The clams for the dinner were from Alligator Point and the Apalachicola oysters from 13 Mile Brand.”

He continued, “The oysters from Apalachicola and 13 Mile in particular are so fresh and delicious. I don’t like to do too much to them because they’re so flavorful. I’m a purist who doesn’t like anything on my oyster; the oyster does all the work.”

McDonald personally enjoys scalloping in Cape San Blas and prepares them for catered events; however, he didn’t add scallops to the VIE dinner menu as they are not in season.

Nonetheless, at events where McDonald serves freshly shucked, raw oysters on a half shell, he usually puts lemon wedges on the side and whips up either a Meyer lemon mignonette or a cucumber mignonette as an option, which, used sparingly, enhances the oyster’s flavor.

To prepare McDonald’s cucumber mignonette, peel and core a cucumber and then julienne it on a mandoline (this makes long, skinny strips). Mince the julienned cucumber. McDonald combines sparkling wine, champagne vinegar, and freshly ground black pepper and adds the cucumber to the mixture. His advice: prepare this mignonette a day in advance so that the flavors blend.

Photo by Bob Brown.

Apalachicola oysters never go dormant, although they do become a little less productive in winter. The winter bars to which local oystermen refer are beds where Apalachicola oysters can be harvested from October to June. The bay water is cold, the wind bites, and the oysters are full of spats (babies). Other oyster regions of North America lack the distinction of an appellation. However, just as champagne can only be called such if the wine comes from the Champagne region of France, only oysters from Apalachicola Bay go by the Apalachicola name.

Speaking of champagne and oysters, the two together create a food and wine pairing that is unmatched. Perhaps it’s the sharpness of the bubbles against the buttery, briny oyster that makes the combination perfect, or perhaps it’s the long-held belief that oysters are an aphrodisiac. There is something adventurous, artful, and sensual about eating oysters. Just refer to Anthony Bourdain’s memoir Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly. Bourdain’s first experience eating oysters was in France when, as a pubescent boy, he was on a family vacation.

He writes, “… and with one bite and a slurp, wolfed it down. It tasted of seawater … of brine and flesh…and somehow…of the future.

“Everything was different now. Everything.

“I’d not only survived—I’d enjoyed.

“This, I knew, was the magic of which I had until now been only dimly and spitefully aware. I was hooked. My parents’ shudders, my little brother’s expression of unrestrained revulsion and amazement only reinforced the sense I had, somehow, become a man. I had had an adventure, tasted forbidden fruit and everything that followed in my life—the food, the long and often stupid and self-destructive chase for the next thing, whether it was drugs, sex or some other new sensation—would all stem from this moment.

“I’d learned something. Viscerally, instinctively, spiritually—even in some small, precursive way, sexually—and there was no turning back. The genie was out of the bottle. My life as a cook, and a chef, had begun.

“Food had power.”

Raw oysters on the half shell alone or with a dollop of homemade sauce accompanied by champagne or prosecco are sure to impress, especially a date. An oyster-tasting party with a variety of East and West Coast oysters or a Gulf Coast oyster-and-beer party are both great ways to entertain. Either way, consider the following from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services when preparing oysters to serve at home:

- Buy oysters fresh (on the day of event, if possible).

- Make sure the only thing you smell is a sea breeze scent.

- In storing them, don’t place oysters directly on ice or immersed in water.

- If purchased in advance, refrigerate in a container with a lid slightly open for up to seven days and drain excess liquid daily.

- Live oysters should close tightly when the shell is tapped; discard any that do not close.

- Keep shucked oysters refrigerated for up to five days.

When it comes to shucking, hire someone or have these tricky-to-open mollusks shucked for you. Shucking on your own? Buy the proper gloves and knife and learn how to do it by watching a pro at a local fish store or at a restaurant.

At the third annual Apalachicola Oyster Cook-Off in January, oystermen and others competed for a trophy, the prize for the best-tasting oyster preparation. The extremely popular local event benefits the Apalachicola Volunteer Fire Department. Concerned-citizen-turned-coordinator Marisa Getter developed the event to raise funds for repairs to hydrants and to purchase equipment that saves lives. The cook-off grossed approximately $33,000 this year. About the winning dish prepared by the Eastpoint Volunteer Fire Department (EVFD), Getter said, “It was delicious.”

EVFD Deputy Chief Jim Joyner said, “It’s a variation of Oysters Rockefeller.”

There is some disagreement among food historians about whether the original recipe for Oysters Rockefeller had spinach in it. Anyone familiar with the dish, however, knows that it was a rich topping created by the son of the founder of Antoine’s of New Orleans and named for the richest man in America at the time, John D. Rockefeller. The Eastpoint Fire Department’s twist on the oyster classic layers a casserole dish with softened cream cheese, spinach, oysters, toasted breadcrumbs, bacon bits, and smoked Gouda cheese. The team repeats the layering and then bakes the dish on a grill.

A stroll around the waterfront where competitors’ tents were pitched revealed conversations about the anger and frustration oystermen feel over the control of freshwater into the Apalachicola River basin on the part of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. It’s a topic that can’t be ignored when talking about Apalachicola oysters.

Former oysterman Joyner said, “Everybody’s angry. At this time of year, tongers are capable of hauling ten to fifteen bags per day, twenty-five to thirty when the salinity and freshwater ratio is correct. We can handle what Mother Nature brings. But, now that they [U.S. Army Corps of Engineers] have cut our water supply, oystermen are hauling five bags a day.”

The Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers of western Georgia and eastern Alabama meet at Lake Seminole in the southwestern corner of Georgia where it borders Florida. From Lake Seminole, water flows into the southbound Apalachicola River through northern Florida to the Apalachicola Bay and into the Gulf of Mexico. Deputy Chief Joyner was referring to the controversial control of water from the reservoirs north of Atlanta that not only affects the livelihood of hundreds of oystermen and thousands of families tied to the industry but also the biological productivity of the previously sheltered estuarine complex. It carries the highest ranking for shellfish harvesting and is really quite unique in the world. What happens north of Atlanta to satisfy the drinking water needs of one of the largest cities in the U.S. influences what happens in the Apalachicola River basin and bay.

According to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, “… it [the estuary] is influenced strongly by the amount, timing, and duration of freshwater inflow.” Actual drought conditions north of Apalachicola coupled with reduced freshwater flow from the ACF have increased salinity and created an artificial drought in the basin. Such a reduction in freshwater compromises productivity and can kill oysters. It is a delicate balance.

Equally important, the Apalachicola oysters, known and revered for their year-round consistent flavor that is mellow, mildly briny, and hints at a melon taste, are affected. EVFD Chief George Pruett summed it up, saying, “We are half seafood and half tourism here. When the bay and the Gulf aren’t doing well, half of us in this area aren’t doing well.”

For such a pleasure-filled and delicious food, the controversial issues surrounding the production and harvest of oysters are complex and disquieting. The disputes are well into their second decade as a matter for the courts. Comparing the water issue to other challenges Apalachicolans have overcome, like hurricanes, Jim Joyner settles on a thought: “We’ll get by this.”

“Expensive” Oysters

Fried Oysters with Lemon Butter Cream Sauce

Oyster Cook-Off contender John Solomon representing Team Retsyo (oyster spelled backwards). Solomon, a corrections officer, is the head of the annual Florida Seafood Festival in Apalachicola, which is held in early November.

Oysters

In a bowl, combine equal parts flour and cornmeal with Cajun seasoning to taste. (Amounts will depend on the number of oysters being breaded.)

Dredge fresh oysters in the mix.

Deep-fry the oysters in peanut oil (enough to brown the outside but keep the inside tender—about 1 minute).

Place each oyster back on a half shell.

Lemon Butter Cream Sauce

Ingredients:

3 lemons

1 1/2 sticks butter

2 cups white wine

2 shallots, minced

2 cloves garlic, minced

2 pints half-and-half

5 medium to large shrimp, peeled and deveined

In a small saucepan on medium heat, melt a tablespoon of butter and add the shallots and garlic. Cook until slightly caramelized. Rough chop the shrimp and combine with shallots and garlic, stirring constantly, until the shrimp turns pink. Add 2 cups of white wine and squeeze the juice of 2 1/2 lemons into the mixture. Turn heat to medium until mixture starts to simmer and allow it to simmer for a few minutes. Add half-and-half. Reduce heat to low and add the rest of the butter in small portions and whisk until each piece has melted. Once the butter is melted, allow mixture to cook for approximately 5 minutes, stirring slowly and consistently. Strain the shallot/garlic cream sauce into a separate saucepan and finish with the juice of the remaining half lemon.

Drizzle the cream sauce over the fried oysters in their shells and add a dollop of caviar to top it off.

Song Link

“Apalachicola, Fla.” (Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters)

http://tinysong.com/1aP3t

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE