vie-magazine-Joan-Salter-hero-min

Finding Family Across Two Worlds

A Survivor’s Tale

By Anthea Gerrie |

Photography courtesy of Joan Salter

Imagine the trauma of being born in the wrong place at the wrong time and having to flee for your life before you are even old enough for kindergarten. Envision being smuggled out of Paris in a laundry van at the age of two, being arrested at the Spanish border after a failed escape months later, and being locked in prison with your mother.

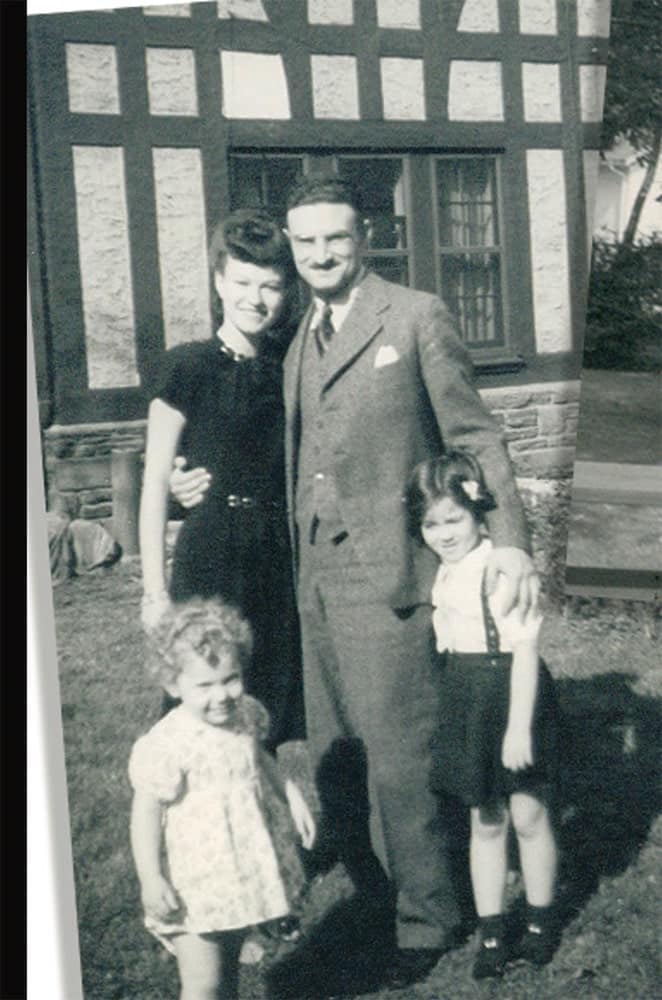

Young Holocaust survivor Joan Salter (right) with her American foster mother, Betty Farell, in 1949

Now envision a daring rescue mission seeing you transported to a new life in America. Your first memory is of the beautiful doctor’s wife who tucks you up in bed in your new bedroom with its own bathroom.

And finally, confront a dramatic third act, which sees you returning home, aged seven, from the Philadelphia school where you have pledged allegiance to the flag every morning, to be told the only home you can remember is not your own, and Joan Farell is not your real name. You were born Fanny Zimetbaum to Jewish refugees who fled the Nazis, survived World War II, and now want you back to live with them in London.

This was no fairy-tale ending for Joan Salter; it turned out to be a nightmare scenario that saw her crisscrossing the Atlantic for more than ten years, never feeling sure whether the American foster parents who raised her or the birth parents who barely spoke English were her real family. “My closest bond is actually with my foster sister Davida,” she says of the Boston-based septuagenarian and the children and grandchildren who think of her as the auntie who kept on crossing the Atlantic to attend family weddings and bar mitzvahs.

Joan Salter in 2020 with her husband, Martin, and their eldest daughter, Rochelle, taken as part of a project for the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust | Photo by Frederic Aranda

Joan, now 81, and Davida first met in 1949, when the older girl was invited back to Philadelphia for a vacation and stayed for months. “The Farells adopted Davida in 1947 after I left for England,” says Salter. “My foster father, who adored me, was in tears when I left. I remember telling him, ‘Don’t worry, it’s all a mistake; I’ll come back.’”

Within hours of being waved off at the airport, Salter was reunited with a half sister from whom she had been separated for years and to whom she never became close. She recalls the reunion with her birth parents. “I remember these strangers coming toward us, broken by their years on the run and losing their children. They were traumatized by what they had been through and losing all but one of each of their immediate families.”

Life in London turned out to be anything but a happy ending. “We lived above a shop where the biggest room in the flat was the kitchen, which had a single cold-water tap, and my sister and I slept in the living room.

“I felt no kinship; they were foreigners, and my mother barely spoke English. My parents worked in a factory and were out from seven in the morning until seven or eight at night. I had to try and light the fire when I came home from school; I was so cold all the time. And I went from having my own bathroom to using the public baths in our neighborhood once a week.”

Joan (right) and her foster sister Davida (left) with their foster father, Dr. David Farell, and a family friend

For the next decade, Salter would divide her time between her two families. “My foster father would come over to the UK and give lectures, and I would keep going back with him, which made my birth mother black with fury.”

But soon, the good life in Philadelphia started to turn bad as well. “The relationship with my foster mother broke down as I became a teen. If I did something ‘terrible,’ like spill a glass of milk, I was locked in a cupboard. My foster father would come and get me out and say, ‘Mommy didn’t mean it.’”

At seventeen, Salter decided life in London was the lesser of two evils. “I knew my foster mother, whom I now realize had a personality disorder, was trying to manipulate me and make me feel I wasn’t good enough. I went to a youth club that had just built a girls’ hostel, and the warden offered me a room there.

“Through the youth service, I met my husband, Martin, and we got married in 1959. My foster parents came for the wedding, which probably broke my birth mother’s heart—but they were as much my parents as the ones I was born to, and Davida was one of my bridesmaids.”

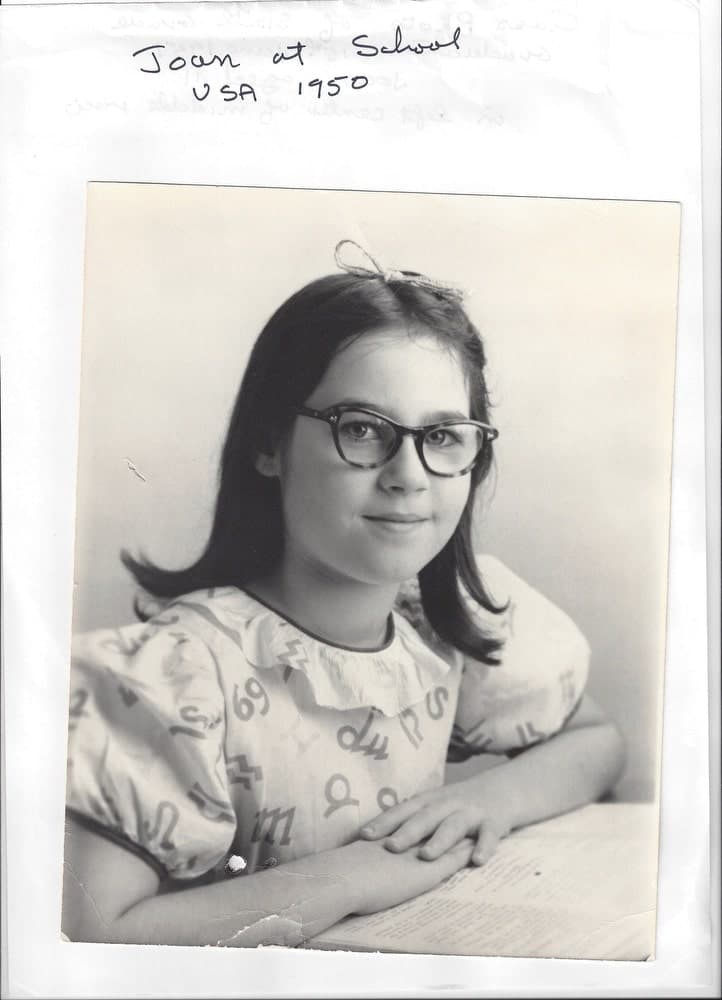

Joan’s school photo, 1950

Despite her difficult childhood, Salter has enjoyed a long marriage and has two daughters of her own as well as a grandchild. It took becoming a mother for her to start looking into her early life and discover that what she had thought was a childhood dream about being on a ship with other children and feeling frightened when soldiers boarded was a memory of her actual rescue voyage. She was one of one hundred child refugees to whom the US offered sanctuary, which did not extend to their parents. “I can only guess what my mother must have felt when she agreed to let us go while she remained in Europe,” muses Salter, who went on to earn a master’s degree in Holocaust studies.

After traveling to the US for her foster father’s funeral, Salter insisted on getting answers to questions that had gone unanswered for so long. “When I came home, I sat down with my birth father and started talking to him about his life during the war, and in archives, I found out about the children taken out of Europe by the Quakers and Red Cross from Lisbon—the story of how I got to America.”

Davida and Joan at the wedding of Davida’s daughter Rebecca

As for her birth mother, Salter explains, “We never got close because she was like a ghost. But I did discover that in Paris, she was warned a roundup of Jews was due to take place, so we left for the south, smuggled out of the city by the Resistance. We were reunited briefly with my father, who escaped Paris separately, but he was captured at the Spanish border in another roundup. He was eventually rescued and transported to the UK, where he was drafted.”

Salter resumed her transatlantic travels at Davida’s begging when her foster mother became ill. “She died about six months before my birth mother in 1989. My father was diagnosed with lung cancer soon after and died the following year. By that time, I had made peace with him.”

Now in her ninth decade, Salter, whose portrait hangs in a new exhibition of Holocaust victims with their descendants in London’s Imperial War Museum, has finally made peace with herself.

“My double life growing up was awful while it lasted, but you can’t blame your past for everything.

Some of what is good comes from my American family, some from my birth parents, and some of it is, I believe, genetic.

“I don’t differentiate between birth and foster; both were my parents and both molded me. Using my head, I know there is no point in regretting, but using my heart, I know going back to England was the only way to become master of myself rather than staying in America to be that lovely little girl my foster mother wanted, which I wasn’t anymore.

“I turned out to be very strong, like my mother, but it took me a long time to get there.”

— V —

Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors can be seen at the Imperial War Museum London until January 9, 2022. Visit IWM.org.uk to learn more.

Anthea Gerrie is based in the UK but travels the world in search of stories. Her special interests are architecture and design, culture, food, and drink, as well as the best places to visit in the world’s great playgrounds. She is a regular contributor to the Daily Mail, the Independent, and Blueprint.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE