vie-magazine-chris-alvarado-driftwood-guitars-hero-min

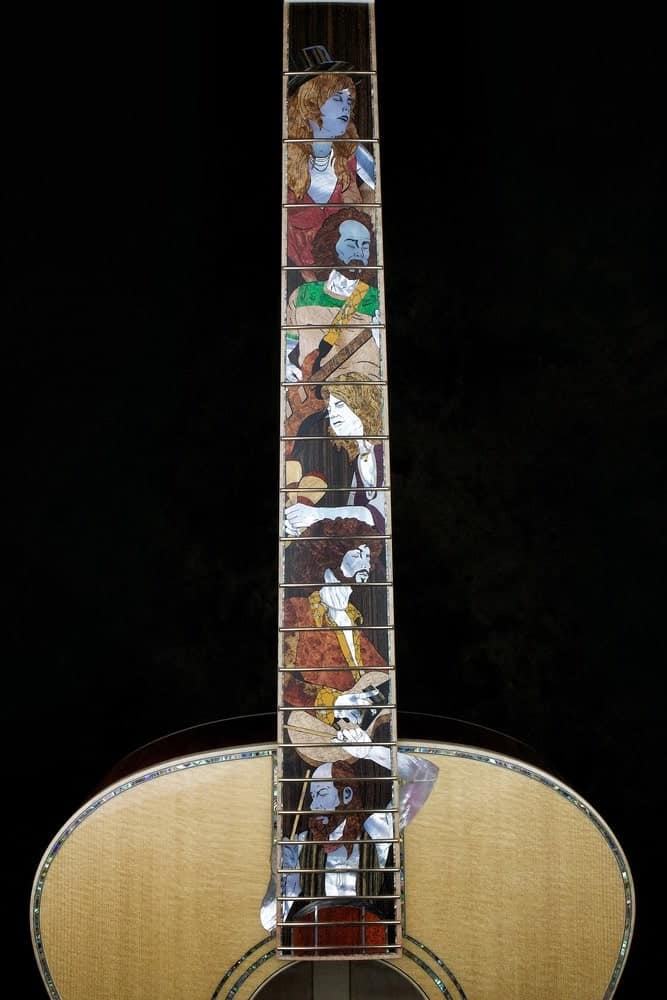

A Johnny Cash–themed acoustic guitar with incredible inlay details created by musician and luthier Chris Alvarado of Driftwood Guitars

Acoustic Feedback

By Tori Phelps | Photography by Chris Alvarado

Singer-songwriter and guitar artisan Chris Alvarado riffs on the benefits of patience, his definition of “making it,” and why he’s the luckiest guy in the world.

Driftwood is a reminder of what Mother Nature can do when she’s not even trying. Washed on the waves and shaped by time, it evokes images of coastal life at its laid-back, enchanting best. When Chris Alvarado named his custom guitar company Driftwood Guitars as an homage to his beloved Florida Gulf Coast home near Scenic Highway 30-A, he couldn’t have imagined that it would become synonymous with the kind of exceptional instruments that household-name artists are willing to wait years to own.

Growing up on the Emerald Coast, Alvarado didn’t always appreciate the area’s unique beauty; it took being stationed in Alaska with the Air Force to discover that he missed it. The time away helped him realize something else: he wanted to perform music. As he waded into the area’s vibrant coffeehouse scene, he became a fan favorite and soon was playing every weekend.

- The inlay on this Driftwood Guitar was inspired by legendary folk artist Bob Dylan.

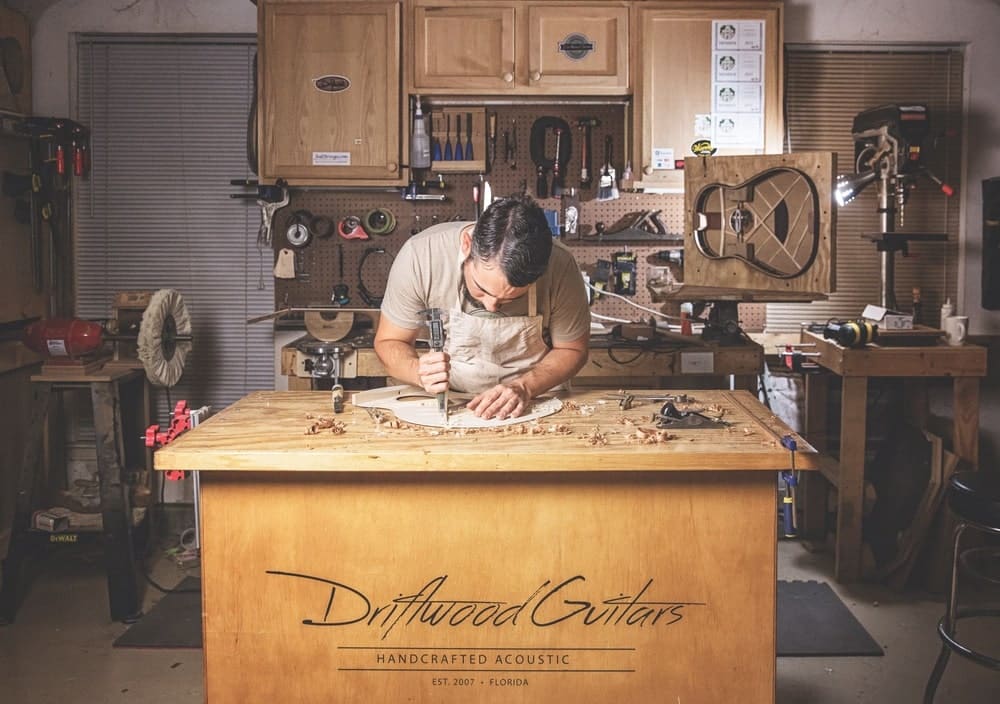

- Alvarado founded Driftwood Guitars in 2007 and has since been making custom instruments on commission for clients, celebrity musicians, charity organizations, events, and more.

By then, he’d been strumming an acoustic guitar for years. He’d picked it up in junior high—mostly to impress girls, he admits—after being awestruck by Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide.” His dad, a full-time saxophone player, encouraged both an artistic and a technical appreciation for music, as well as a passion for working with his hands.

In search of a new hobby, he tripped onto an idea after an Air Force colleague showed off an electric guitar he’d made one weekend. “It was a holy s*** moment for me,” Alvarado recalls. “I kind of said out loud, ‘I can build an acoustic guitar.’”

His friend’s advice? “Good luck with that.”

His dad, a full-time saxophone player, encouraged both an artistic and a technical appreciation for music, as well as a passion for working with his hands.

While an electric guitar can be built in a matter of days, an acoustic guitar made by hand takes months. But Alvarado was already fascinated by the idea, devouring books on the subject and “building” guitars in his head over and over. When he felt ready, he bought the materials and produced his first real acoustic guitar. A really terrible acoustic guitar, he concedes. Undeterred, he launched into a second, much-improved attempt.

With his military service drawing to a close, Alvarado decided to give music a genuine try. Nashville and Los Angeles were the obvious destinations. Still, his dad suggested that if he wanted to make a living as a musician—rather than just get famous—he should consider returning to the Emerald Coast. His father’s career was proof, after all, that 30-A could support the profession. Alvarado agreed, and, within months, his music gigs were paying the bills.

Naturally, he played his guitars during performances, and people’s interest in the unique instruments led to commissions. But it was one commission in particular that put Driftwood Guitars on the map and finally convinced Alvarado that his little hobby was neither little nor a hobby.

- A custom Driftwood Guitar featuring a detailed inlay of the Nashville city skyline

- Alvarado’s Driftwood Guitars and ukuleles feature many types of wood options with details made from abalone shell, bone, ivory, and more. See details on his website. | Photo by Shelly Swanger

- Alvarado founded Driftwood Guitars in 2007 and has since been making custom instruments on commission for clients, celebrity musicians, charity organizations, events, and more.

- Alvarado founded Driftwood Guitars in 2007 and has since been making custom instruments on commission for clients, celebrity musicians, charity organizations, events, and more.

- Photo by Shelly Swanger

- Photo by Shelly Swanger

- Photo by Shelly Swanger

Alvarado knew Duke Bardwell as Elvis’s bass player, as well as a fellow local musician. But as soon as Bardwell picked up one of Alvarado’s guitars and started to play, he turned into a customer. That job certainly raised his profile, but more importantly, the relationship he developed with Bardwell became a model for every customer relationship going forward. “It was the first time I had communicated with a client on that level; we talked on the phone almost daily while I was building it, and we became good friends,” Alvarado says. “That relationship made me want to build something extra special for him.”

In the years since, Driftwood Guitars has raised the bar in the custom guitar world. Alvarado has built guitars for music megastars like Florida Georgia Line’s Brian Kelly and powerhouse organizations such as Rolls Royce and the Grammys. In a fun twist, the Grammy guitar he built ended up in the hands of Mick Fleetwood, a full-circle moment for the kid who got into music because of a Fleetwood Mac song.

His waiting list for a commissioned instrument runs up to two years these days, but clients are willing to queue up because the finished product is as much an emotional payoff as a musical one. Selecting everything from the soundboard wood to the rib rest bevel gives clients a rare investment in their guitars. And then there are the inlays, which began with Duke Bardwell and have now become a Driftwood hallmark. These abalone symbols, words, and pictures are as individual as fingerprints and elevate each instrument to a visual work of art.

The problem, Alvarado points out, is that no two pieces of wood are the same, even if they come from the same tree.

But even those customized elements don’t tell the whole story of what makes Driftwood Guitars worth the wait and the price tag. To understand the cult of Driftwood, you have to understand Alvarado and his process. As he did with Bardwell, he gets to know each client on a gut level, drilling down to the things that give their lives meaning. Take the guitar he’s currently building, for example. Once he learned that the client treasured a piece of barnwood from a long-sold family farm, it was a no-brainer to include that fragment in the guitar itself. But perhaps the most remarkable illustration is a guitar he built for the two remaining members of a three-man band. Alvarado incorporated ashes from the deceased trio member into the guitar so that, as he says, “Every time it’s played, all three of them are playing together again.”

Beauty and meaning are important, but Driftwood Guitars wouldn’t enjoy its lofty status without producing the best quality instruments any client—even a master—has ever played. And that, Alvarado asserts, is his main objective.

The sheer fact that his guitars are handmade goes a long way toward achieving that goal. Factory built, as it turns out, is a surefire way to churn out an instrument created for everyone and, as a result, for no one. In their focus on mass production, factories run the wood through a machine set to a specific dimension. The problem, Alvarado points out, is that no two pieces of wood are the same, even if they come from the same tree.

Chris Alvarado | Photo by Shelly Swanger

He explains that the key to musicality is working with each piece of wood until it tells you it’s ready. With his years of experience and the patience of a true believer, this readiness is something he can feel. And it informs every step of the process. While Alvarado devotes two or three days to shaping the braces, also called “voicing” the guitar, factories spend thirty seconds knocking the braces down. That single process exemplifies the entire difference. “Not only am I voicing that particular guitar, but I’m voicing it for that particular client,” he says of his precision. “I know what kind of music he’s going to play, what kind of strings he’s going to put on it, and whether he’ll play it in Florida or Minnesota.”

Playing his optimized guitars could be one reason Alvarado is such a popular performer along 30-A, though a résumé full of singing and songwriting awards points to something more substantial. Among his most distinguished honors was winning the Florida Grammy Showcase in 2012—but not for the reason you’d think. “I felt like I’d made it,” he recalls. “And then I realized that I’d ‘made it’ before that award because I was already doing what I love. I play music and build acoustic guitars, and I feed my whole family with that. I’ve gotta be one of the luckiest human beings on earth.”

His long-ago dreams of playing music and building guitars didn’t include living on the road or in a huge, smoggy city. That’s why, regardless of his “potential,” Alvarado is unapologetic about refusing to reach for bigger, better, more. He admits that he aims to be the best at what he does and doesn’t mind being recognized for it. “But in the end,” he maintains, “this is what I’m going to be doing: building guitars in Freeport, Florida.”

To learn more about Driftwood Guitars or to access Chris Alvarado’s performance schedule, visit Driftwood-Guitars.com.

Tori Phelps has been a writer and editor for nearly twenty years. A publishing industry veteran and longtime VIE collaborator, Phelps lives with three kids, two cats, and one husband in Charleston, South Carolina.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE