vie-magazine-micki-glenn-hero-min

In the Blink of an Eye

A Survivor’s Story

By Micki Koch Glenn

I wasn’t just scuba diving for fun. I was one of about twenty guests aboard Sea Dancer, a 120-foot liveaboard dive boat, and we were on a mission: to observe and photograph sharks off uninhabited French Cay in the Turks and Caicos Islands. I was forty-one years old, a former radiology director, and by 2002 I had been managing my husband Mike’s orthopedic surgery practice for several years. Among the others living on board the Sea Dancer were a vascular surgeon and an ICU nurse. We were relaxing after the first dive of the day when I decided to join several friends snorkeling during our surface interval.

Drifting at the surface, clad only in a gold lamé bikini, I was not surprised to see a seven-foot female shark just beneath my flippers. Mike, still in scuba gear, had swum deeper to take photographs in the cathedral-like beams of light that fell through the bright blue water and faded to dark purple and then black. Five days into the trip, we had become accustomed to having sharks nearby. This shark stopped abruptly and changed direction. She moved slowly upright, aligning her body vertically with mine, and made full contact with me, so that I was sandwiched between her dorsal and right pectoral fins. Slowly and deliberately, she slid all the way up my body. I stared into her eye, inches away—a beautiful gray-green orb with a vertical pupil. I saw the slit of her closed mouth. I thought in that moment that I was the luckiest person in the world. Suddenly, the shark bent her head to the left, flicked her tail gently, and glided away.

I began to exhale, then suddenly a powerful surge of water hit me just before the shark slammed into the right side of my upper body. Her upper rows of teeth raked across my back all the way to my spine and took the posterior half of my armpit and my entire triceps, almost completely stripping the flesh from my upper arm. Her lower jaw sliced through my breast and my biceps. She began thrashing with such force that I suffered whiplash. Finally, she glided away and slid beneath the boat. It was about eight o’clock in the morning on a beautiful sunny day—November 14, 2002.

The water was deep crimson. Looking around, I saw four other sharks. I also saw my ragged flesh and bare humerus. What I felt was beyond terror. I began kicking as hard as I could toward the boat, paddling with my uninjured left arm. I glanced behind me, and the water was so red, I couldn’t see my right arm. Then I saw a chalky white creature jerking along behind me, and I stopped for a second. As it drifted closer, I realized that it was my own limp right hand, which had been paralyzed by the attack.

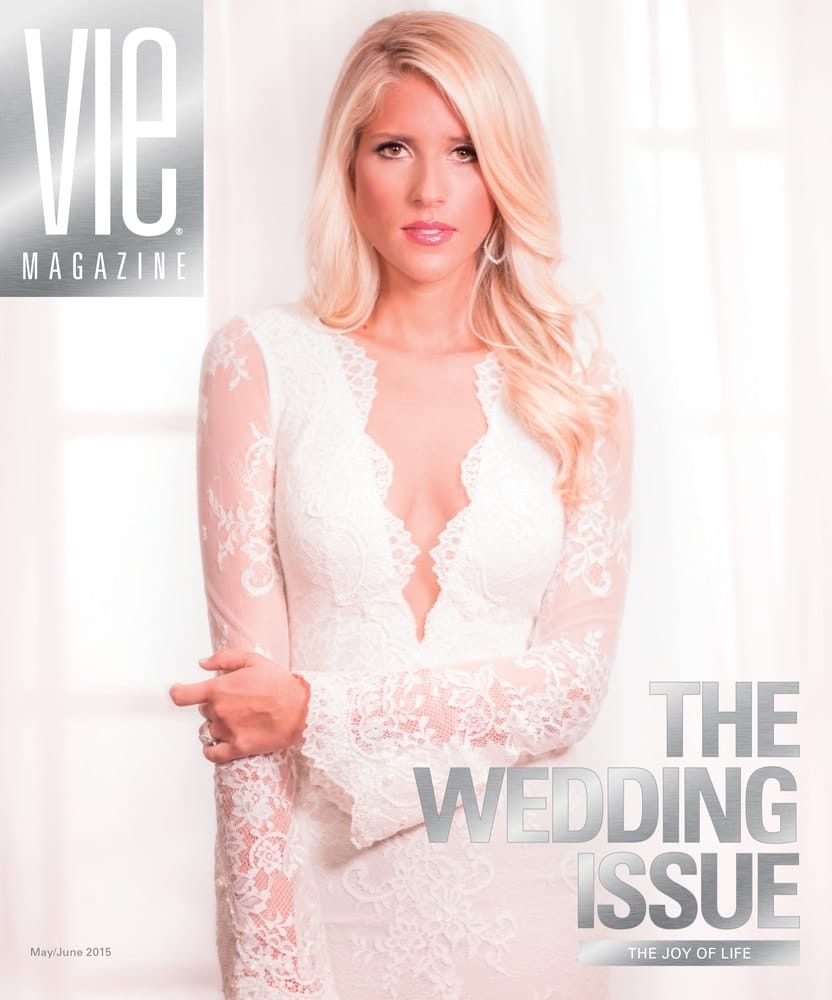

- Micki Koch Glenn and her husband, Dr. James Michael “Mike” Glenn

Nancy Birchett, who had been snorkeling nearby, reached me and helped propel me to the boat. I climbed two ladders to reach a platform large enough for people to help me and then collapsed. As I lay on the stern in the bright sunshine, the chances that I would survive were fading fast. I began screaming for Mike. I heard his tank drop heavily on the platform a deck below, and within seconds he was kneeling beside me.

Mike reached into my shoulder and groped for the torn end of my brachial artery, which was ejecting the fountain of blood I had seen in the water. Randy Samberson, the vascular surgeon, compressed the vessel Mike held between his fingers with a hemostat. Blood still pumped out. Mike worked his way deeper into the wound to grip my artery higher up. That’s when the pain hit. It was surgery without anesthesia. I began to scream. Meanwhile, nurse Libba Shaw started an IV.

Quickly, I developed a mantra: Pain is my friend. My mantra carried me through the excruciating journey to the hospital by dinghy, police boat, helicopter, ambulance, and, at last, Coast Guard jet. Over the next twelve days, doctors operated on me six times, and I required thirteen units of blood. I survived the attack that should have killed me, but the more profound drama—the ordeal of trying to reenter the world—was just beginning.

I survived the attack that should have killed me, but the more profound drama—the ordeal of trying to reenter the world—was just beginning.

I needed to focus on something every minute, because as soon as I relaxed, the hospital walls would turn into the sea, and I relived the shark attack over and over. I would wake screaming, with my mother standing over me saying, “Honey, it’s just a nightmare.”

The day before Thanksgiving, Mike and I returned to our home in Destin, Florida. Mike grew up in the Niceville area, and I’ve lived in Okaloosa or Walton County since 1985. We were overwhelmed by the outpouring of love, concern, prayers, flowers, cards, food, and support we received from hundreds of local friends and acquaintances.

After the shark attack, I felt as though I’d been cleaved into two identities: the Micki I knew and loved was loud and clear in my head, but the new Micki—injured, frightened, and timid—emerged as the dominant me. To my dismay, she controlled my feelings and my body. When I had flashbacks in the middle of the night, I’d retreat into my closet and curl up in a ball, pressing my back into a corner so that I could see anything approaching, and I would cry. Flashbacks are an all-out assault on the emotional system. I was frightened to my core, disfigured, and in a tremendous amount of pain—and narcotics made me throw up. Simple tasks such as dressing myself, inserting my contact lenses, preparing food, washing dishes, tying my shoes, and learning to write with my left hand felt overwhelming.

I had the sensation that pieces of me were scattered in the ocean, and they were; physical pieces of me were missing. But it was more than that. I felt like I had lost who I was. I had reveled in my life and my fearlessness. Things I did, such as stepping off the Okaloosa Island Pier into an eighteen-foot crest in a hurricane surge or galloping on my big Swedish Warmblood horse, Gent, in the woods on Eglin Air Force Base reservation at night while watching the tracers from gunships doing night ops—those aren’t just things I do. That’s who I am.

I developed a strategy. Each morning when I woke with a cloak of fear and despair suffocating me, I chose to smile. Sometimes tears were streaming down my face, but I forced my lips into a big smile, and I made a decision to be positive. It was powerful and one of the few things I could control. Had I chosen to give in to despair instead of forcing myself to smile, I would have slid into self-pity.

I celebrate November 14, the day I survived. I typically do something fun like horseback riding followed by a two-hour massage. Then I soak in a hot bath and sip a nice red wine while listening to classical music or jazz. Then I dress up and go out to dinner. I don’t suppress my memories; I review what was happening to me hour by hour. It’s not bad or sad—it’s just remembering and feeling blessed to be alive.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE