vie-magazine-zaha-hadid-architecture-hero

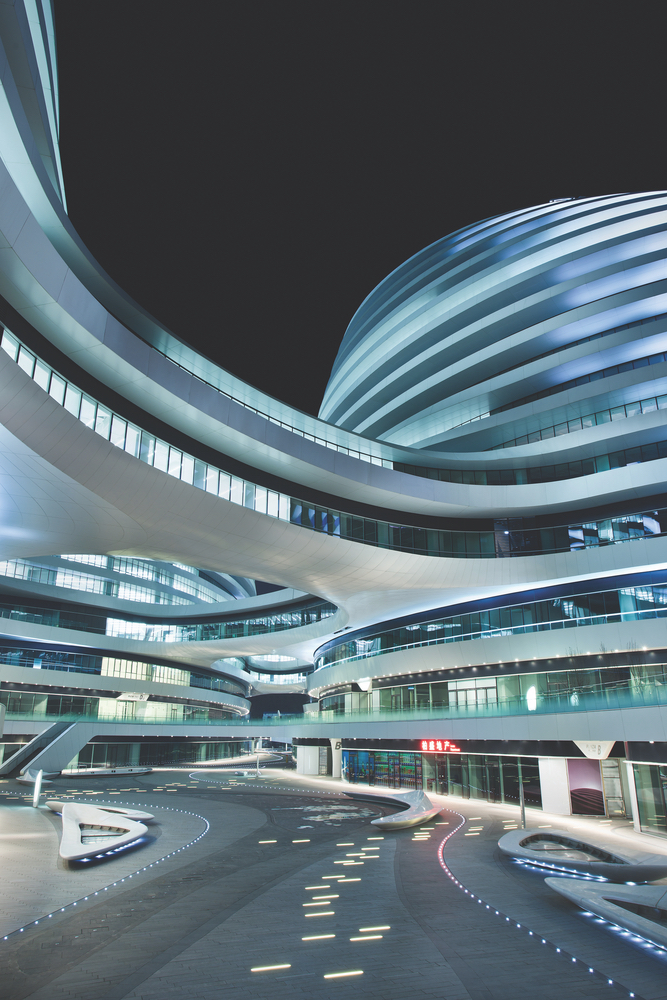

Sky SOHO office and retail building near Hongqiao Transportation Hub in Shanghai, China. Photo by chuckstock / Shutterstock

Zaha Hadid’s Monumental Legacy

1950–2016

By Tori Phelps

To paraphrase Frank Sinatra, Zaha Hadid did it her way. The late architect shattered barriers and created a groundbreaking career simply by chasing her passion.

As a woman, the door to architectural success was barely ajar. As an Iraqi, it might as well have been closed. But Hadid either didn’t notice—or didn’t care. Ultimately, her life was punctuated by a series of firsts that won’t be seen again.

She was the first woman and the first Iraqi to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize, considered the Nobel Prize of architecture, and the first woman in her own right to receive the Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Yet Hadid was more than just a remarkable female architect; she was one of the best architects the world has seen. Period.

Born October 31, 1950, in Baghdad to an artist mother and a father who cofounded the National Democratic Party, Hadid did have one advantage: an upper-class family. For her, that meant boarding schools in England and Switzerland and mathematics studies at the American University of Beirut.

In 1972, she returned to England to study at London’s Architectural Association School of Architecture. Hadid clearly impressed her instructors; she joined them at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, earning partner status a short time later. She ventured out on her own in 1979 when she launched an eponymous London-based architecture firm.

Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan. Photo by Elnur / Shutterstock

A few years later, Harvard called. Hadid left her adopted home country—she had become a naturalized citizen of the United Kingdom—to accept a Kenzo Tange Professorship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. She taught off and on for decades at prestigious institutions like Yale and Columbia University and in cities from Chicago to Hamburg to Vienna.

[the_blockquote]She taught off and on for decades at prestigious institutions like Yale and Columbia University and in cities from Chicago to Hamburg to Vienna.[/the_blockquote]

Teaching the next generation of architects didn’t slow her creative streak, and in 1988, her inclusion in an architectural drawing exhibition at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art put her on the map. She began racking up commissions in every corner of the world, including standouts like the MAXXI(National Museum of the 21st Century Arts) in Rome, Italy. According to Hadid, the MAXXI, with its curved concrete walls and suspended black staircases, was intended to be “a new fluid kind of spatiality of multiple perspective points and fragmented geometry, designed to embody the chaotic fluidity of modern life.”

China’s Guangzhou Opera House was another feather in her professional cap. Noted for its harmonious integration with its riverside locale, Hadid’s design was influenced by the way erosion changes river valleys.

Then, when the city she loved landed a bid for the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, Hadid was tapped to design the London Aquatics Centre, which was seen on televisions around the world.

- The state-of-the-art Guangzhou Opera House lights up in Guangzhou, China, along the Pearl River. Photo by mary416 / Shutterstock

- Galaxy SOHO office, retail, and entertainment complex in Beijing, China. With no corners or abrupt transitions, the design is a reinvention of the classical Chinese courtyard. Photo by TonyV3112 / Shutterstock

- Interior of the Museum of XXI Century Arts (the MAXXI) in Rome, Italy. Photo by Maxim Apryatin / Shutterstock

Hadid was a pioneer of parametricism, a style that draws heavily on the principles of her first love, mathematics, but her work is also celebrated for its outside-the-box ingenuity. This rare fusion of abilities is, perhaps, why she was drawn to high-profile projects outside of architecture—like upscale furniture, brassware and, in a collaboration with the apparel company Lacoste, an avant-garde boot.

The world took notice of her contributions. Hadid was named to the Forbes list of the world’s most powerful women and as one of Time magazine’s one hundred most influential people in the world.

Not everyone was a fan, however. In its truest form, architecture is an art that reflects a bit of its creator’s soul, and like all art, it invites commentary. Both the public and the critics generally had positive responses to Hadid’s offerings; in fact, they often drew rave reviews. Her critics, though, deemed her structures too grand, too expensive, and too dismissive of ecological concerns. She made no apologies for any of it. Her focus was her art.

The London Aquatics Centre at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford, East London, was inspired by the fluidity of moving water and the River Thames outside. Photo by Ron Ellis / Shutterstock

In what would be the last years of her life, Hadid’s accumulation of achievements picked up speed, a seemingly impossible feat considering her long list of triumphs. In 2010, the Iraqi government finally commissioned her for a project in her homeland: the new headquarters of the Central Bank of Iraq in Baghdad. In the UK, she also received the Stirling Prize, among the most prestigious architecture awards in the United Kingdom, back to back in 2010 and 2011, and in 2012, she was named a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. The year 2015 saw the announcement that she had won the RIBA Gold Medal.

Then, in an abrupt end to an astonishing career, while being treated for bronchitis in a Miami hospital, Hadid died on March 31, 2016, at the age of sixty-five. Her London architectural design firm, Zaha Hadid Architects, remains. Most importantly, her innovative ideas and stunning architectural masterpieces live on as enduring testimonies to a trailblazing virtuosa.

— V —

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE