vie-magazine-alex-beard-hero-min

Alex Beard | Photo by Chris Granger

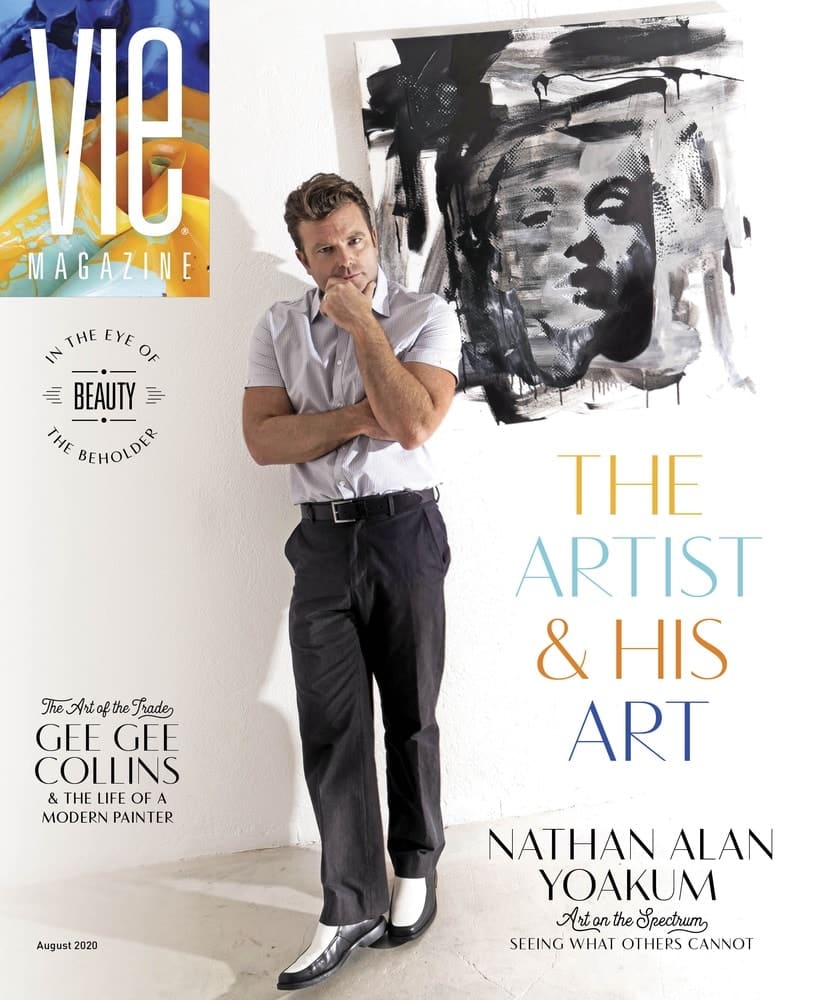

The Call of the Wild

Artist Alex Beard’s Mission to Save the Animals He Celebrates on Canvas

By Tori Phelps | Photography courtesy of Alex Beard

Having a conversation with Alex Beard is a lot like exploring the untamed terrains he loves so much: a little wild, often surprising, and guaranteed to lure you off course. But it’s also a surefire way to learn something about life and about yourself (hmm . . . what is my view on the value of formal education?).

The New Orleans–based painter, author, and reluctant filmmaker is equal parts smart and authentic. He describes his approach to life as “Thoreauvian,” citing a pursuit of off-the-beaten-path zen in any backwoods he can find. But there’s zero chance that he takes himself too seriously. He cheerfully admits, for example, that he knows much of the praise he receives is just people blowing smoke.

His easy laugh only retreats when talking about the life-or-death mission of the Watering Hole Foundation, an organization he founded to help save endangered animals and the world’s remaining wilderness. In other words, he wants to ensure that his paintings won’t be the only place his kids and grandkids can see African elephants.

Beard’s artistic style lends itself well to bringing awareness to the foundation’s cause. While it’s based on gestural painting, Beard had to coin a new term—Abstract Naturalism—for the kind of art he does. In searching for a way to describe it, he realized all of the “categories” were taken. Was it wildlife painting? Not really. Abstract art? Naturalism? It’s none of the above, yet all of the above, he says of the way his nonphotorealistic work mimics the way animals implicitly move in nature.

Wildlife wasn’t something he grew up around, except when he went to the Central Park Zoo. Born and raised in Manhattan, Beard came from a family that believed travel to be the best education. He tagged along with them from an early age, and by the time he was a young teen, he was taking solo international jaunts. Beard rejects the suggestion that junior high is too young for such things, pointing to his grandmother’s unaccompanied move to France at the age of nine to learn the language as evidence that he was actually a late bloomer.

Creativity was another trait his family embraced. His mother worked as a writer and editor for publications like Town & Country, and his uncle, Peter Beard, was a talented photographer and scrap artist. It was “invaluable,” he believes, to have been raised not only among creatives, but among successful creatives. Rather than viewing a career in the arts as a pipe dream or something one lucks into, he saw it as a logical outcome of hard work.

Walking on the Backs of Crocodiles, oil on canvas

Beard opted for formal education at Tufts University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, but his preferred educational method is more Emersonian. “Find someone who knows more about something than you do, and learn what you can from them,” he says. “I’m not as interested in what degrees you have as I am in what you know.”

So he learned and worked … and learned and worked some more. Art was the only career he ever considered (except playing third base for the Yankees, as any New Yorker would), and he made gradual inroads toward building a clientele. His typical cycle involved going to Africa or Asia, where he would complete a bunch of art; returning to the States to show his work at a friend’s apartment, gallery, or any venue that would have him; and then selling the art to pay for his next trip. A bachelor at the time—he’s now married and has two children—he didn’t need much money to fuel that lifestyle. “I wasn’t staying at the Ritz,” he explains. “I would just go to India or wherever for six months and stomp around in the bush.”

“Find someone who knows more about something than you do, and learn what you can from them,”

Over time, people took notice of his ability to bring two-dimensional subjects to life. Both his profile and his prices rose substantially, though he’s far more comfortable with the latter than the former. He admits to being stunned that people not only know what he does, but also actively seek out the chance to view and buy his work. Yet he insists that fame isn’t anything he aspires to. “As soon as you think you’re hot s**t, you stop making anything worth looking at,” says the straight shooter.

Beard creating in pen and ink

Photo by Todd Ritondaro

In addition to a wife and kids who make sure he doesn’t get too big for his britches, Beard’s travels keep him grounded. Literally. It’s not like celebrity counts for anything when he’s sitting around a campfire in Africa or trying to avoid malaria by sleeping under a mosquito net.

And when he comes back to the US, New Orleans takes care of any remaining delusions of grandeur. The fact that locals care more about the person than the profession is one of a thousand things he loves about the city, which he’s called home for twenty-five years. As an artist, he has the freedom to live wherever he wants, but Beard shoots down the idea that he could, in fact, live anywhere else. He revels in New Orleans’s small-town feel and international outlook, adding that its identity as a port city gives it a man-meets-nature environment that’s endlessly inspiring. Besides which, “There are so many cultures here that the culture itself is forgiving of eccentrics,” he sighs. “And I’m kind of eccentric.”

Safely ensconced in a spot that welcomes every form of different, Beard is able to lean into whatever captures his interest. As well as the (usually) large-scale paintings for which he’s best known, he also authors and illustrates critically acclaimed storybooks. The series, Tales from the Watering Hole, features animal-driven plots that are ostensibly for children but which have a message for readers of any age.

Beard in his studio working on a large canvas

His soon-to-be-released fourth book, The Lying King, is an especially timely parable about a warthog ruler who believes he’s immune to the consequences of dishonesty. It’s easy to draw conclusions about whom the main character is based on (which Beard doesn’t deny), but it’s a subject that’s larger than one person. “We’re living in a time when the truth seems to be under siege,” he laments. “When I was growing up, lying was not okay. And I thought it was important to refocus the conversation people have with their children about the consequences of lying.”

He has also dipped his toe into film, with a documentary called Drawing the Line. Filmmaking wasn’t a long-held dream, and he doesn’t plan on making any more. But when he was presented with the opportunity several years ago as a tangible way to fight the horrific slaughter of African elephants, he didn’t consider saying no.

It was a bit of déjà vu for Beard, who had seen similar poaching spikes before. As a child, he was privy to the issue through the work of his photographer uncle, and Beard himself had been at the second-ever ivory burn in the early 1990s. The situation seemed even more dire this time, and he jumped in however he could. “It’s not okay for all the elephants to die. Full stop,” he says. “I did the documentary for no other reason.”

- Emerald Isle Peacock, oil on canvas

Through the Watering Hole Foundation, which he launched in 2012, he’s able to funnel money into projects, organizations, and communities in Africa that are working diligently to stop poaching. This isn’t a tax write-off for him; it’s a primary measure of whether he’s a decent human being. “I’m in a position to help and, frankly, have a responsibility to do so,” he says. “You can’t traipse around these places and see them being destroyed over the course of your lifetime, do nothing about it, and feel okay with yourself.”

So he gives his money away and encourages others to be part of the solution—sometimes during conversations he has at his Magazine Street atelier. He welcomes the public to his studio, in part because he just likes people, but also because he believes that isolated artists are self-referential (read: boring) artists. Mixing with locals and visitors not only prevents him from getting stuck in the rarefied air of the art world, but it upholds his conviction that art is for everyone.

At least, he hopes his art is for everyone. Because the more people who get to know him and his work, the more people who join the conversation about the value of animals and their habitats. He wants viewers to consider the interconnectedness of life when they see his art, though he knows he can’t control that. All he can control is his own motivation. “Everything I do as a person is to teach my children and then their children the same things I was taught,” he explains. “Err on the side of doing the right thing, be open to new things, and give it your best all the time.”

— V —

Tori Phelps has been a writer and editor for nearly twenty years. A publishing industry veteran and longtime VIE collaborator, Phelps lives with three kids, two cats, and one husband in Charleston, South Carolina.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE