vie-magazine-suzanne-pollak-hero-min

Wherever You Go

Look Your Best

By Suzanne Pollak

My first foray into fashion happened when I was six years old, perched on the highest wall in Mogadishu, Somalia. We lived in a pink villa on top of the city, the house and garden enclosed by walls engulfed with thorny, pink bougainvillea. When my brother and I had nothing to do, we climbed through the thorns to sit on the wall, making all kinds of discoveries—fashion was one of them.

One side of the wall overlooked street life: lorries, camels, and people moving down the street, with the Indian Ocean sparkling in the distance. The opposite wall faced a no-man’s-land of bush and wildlife. While sitting on the street side, we peered down and conversed with passersby. Even at our young age, we were struck by the beauty of the Somalis, a tall, thin, elegant, and aristocratic people. The women draped printed cotton around their bodies and wrapped yards of cloth around their heads, making their long necks look even more swan-like and their high cheekbones more prominent. Gold jewelry adorned their ears—not just one little gold droplet but a row up the outer edge of each earlobe. Sometimes a golden bracelet flashed on an arm, the gold gleaming off the color of the skin. Black kohl rimmed almond-shaped eyes.

Somali women look better every day as they go about their chores—buying fruit and fish from the markets, carrying babies on their backs—than any fancy women walking on the Champs-Élysées or Fifth Avenue. Somali women decorated themselves but never overdid, never erred on the side of flashy. The first sight of “flash” we saw was in Playboy. My brother discovered a stash of magazines in the house, which we hauled up the other wall (facing the bush) to peruse the photographs in private under the shade of the flame trees protecting us from the equatorial sun. The Playboy women were foreigners to us, posing with come-on stares. In those days, we saw nudity everywhere and so paid no attention to it. A bare-breasted woman, a nursing mother—it was all part of life out in the open. We ripped out the Playboy pages one by one, flying them on wind currents out to the bush, those Playmates floating to places they never imagined.

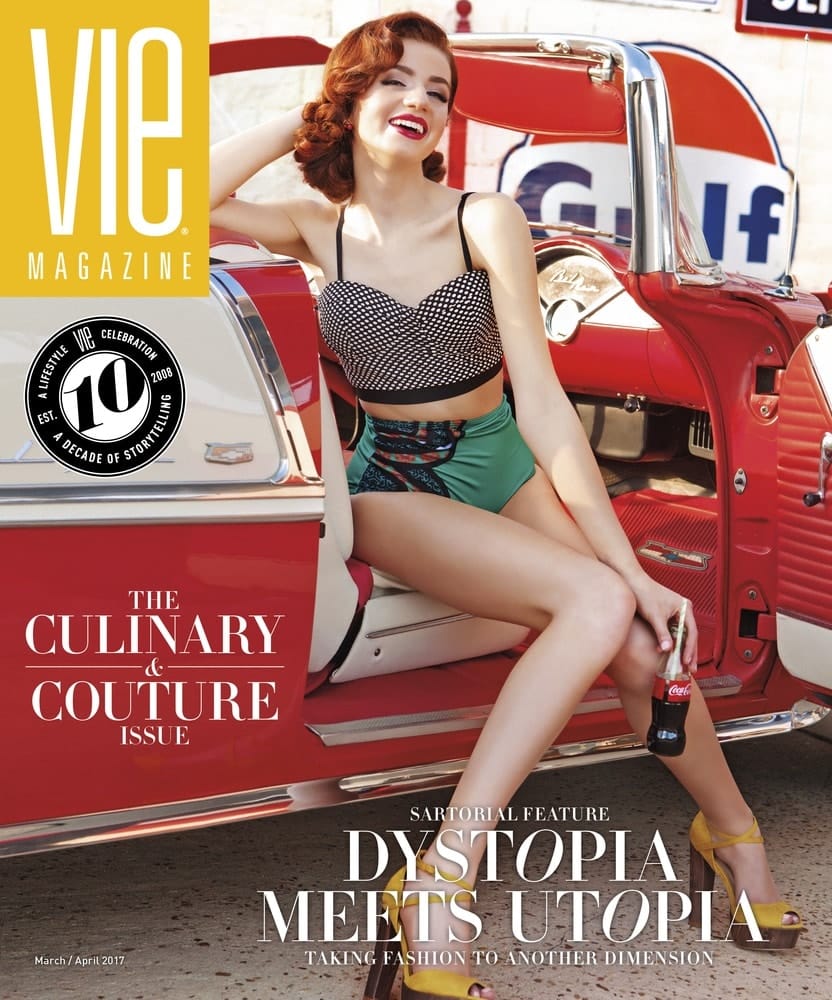

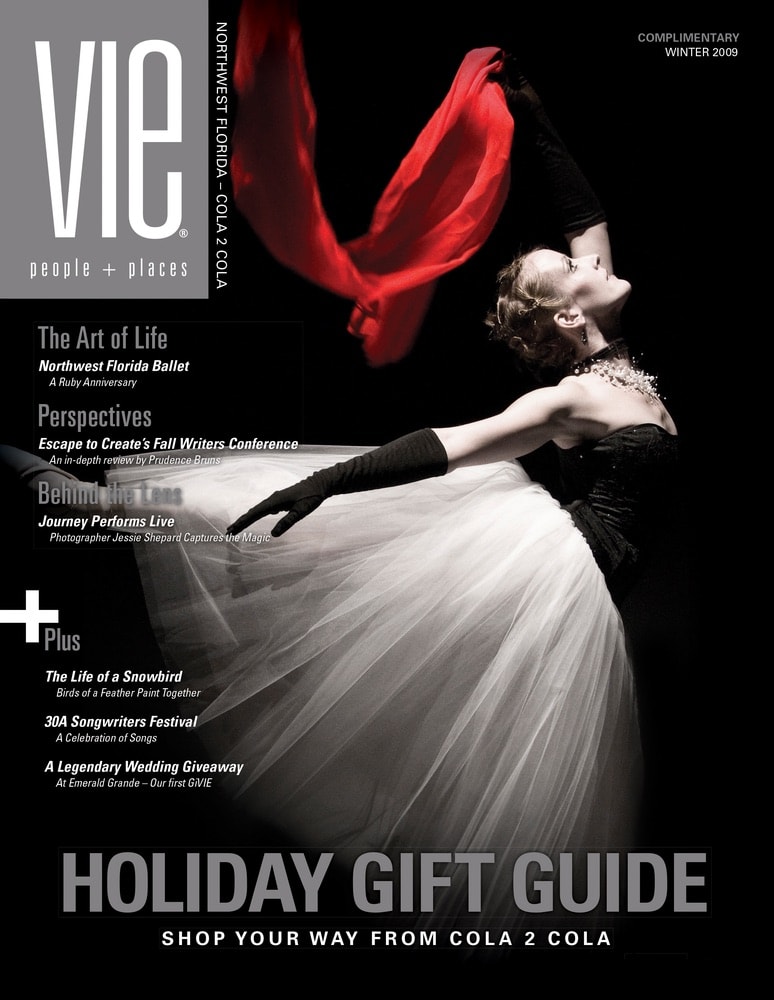

All over the continent, African, American, and European women dressed for parties, no matter what country they were from. My father created the quintessential 1960s cocktail party vibes using his enormous collection of records. The music immediately put one in the mood for a dry martini, a long cigarette held by fingers with nails painted to match lips, and short dresses. Western women wore dazzlingly colored satin or silver-sequined minis, dangling eye-catcher earrings, and dangerously long false eyelashes under a swipe of black eyeliner winging out past the lashes. African and Asian women wrapped their bodies with brilliantly colored cloths. All the women piled bracelets up their arms and sported multiple cocktail rings. Legs were either black or tan, depending on the ethnicity of the owner, but everyone’s skin glowed with baby oil. The women were glamorous, feminine, and mysterious, and I couldn’t wait to be one.

When we lived in Accra, Ghana, I was halfway to being a woman and was allowed to throw a party. Our driver took us to another country so I could purchase a party dress. The shopping trip took all day and required several hours of driving to Togo over paved and mud roads until we reached the capital city of Lomé. Togo A Go-Go was a French store, and it might as well have been couture. We were used to wearing simple shifts sewn from Dutch wax prints, so to see dresses from Paris—this was incredible! My choice was a terry cloth mini with horizontal lime-green and neon-yellow skinny stripes. I carried myself as if Yves Saint Laurent had personally dressed me. Good thing I had such a high opinion of the dress since my mother made me wear it to every party that year and the next until I grew too tall and the dress became too mini. My dress was so perfect that I all wanted to do was to hang out with my best friend, Lucy Miller, and preen. Who cared about dancing to impossibly long, slow dances?

After that party, my father brought me to diplomatic parties all the time. Sometimes my party uniforms were scarves wrapped like the African women I admired. When I finally moved from Monrovia, Liberia, to boarding school in New Hampshire, I went to dinner a few times wrapped in scarves until I realized—wrong! New England is not a place for draping a body in scarves, especially on cold fall nights. The wind, rain, and snow were certainly factors against this form of dress, but so too was the prevailing Puritan sensibility—which was still alive and well.

From these early experiences, I learned that place and culture inform how you put yourself together, what is appropriate, and what is not. Style must suit a soul and must suit a place.

From these early experiences, I learned that place and culture inform how you put yourself together, what is appropriate, and what is not. Style must suit a soul and must suit a place. Here are a few rules I adhere to:

- Being overdressed is as bad as being underdressed—sometimes worse. Always dress appropriately for the occasion at hand. I have seen people dress in black tie for a five o’clock event because the venue was palatial. Unless you are attending the Oscars, it is not okay to go that fancy that early. Black tie only after 7:30 p.m.

- At home, I want to be comfortable. I might take off my shoes because the informality of this gesture immediately puts others at ease. The fancier my clothes, the more likely I am to shed my shoes early. I might not bother to put them on at all. But I only do this at my house, not yours!

- When cooking, I pay attention to hair, jewels, and sleeves. The hair of the home cook must be held back; it cannot be flying around and landing in frying pans. Remove bracelets and long-hanging necklaces until you finish cooking. Rings are magnets for dough and uncooked meat—remove! Having eliminated all other jewelry choices, I rely on big earrings for parties. Watch out, too, for batwing or long sleeves. They gather food, and worse, I’ve even seen them ignite.

- The first thing I think about when going to other houses is my shoes. A house party is a time to put on my most beautiful pair. While I sit in your living room, sipping a cocktail, my shoes are enjoying their time in the spotlight. They are not hidden under a table, as they would be in a restaurant. At least among women, shoes are a great conversation starter. They can get half the room onto common ground. They are your pedestal. (But if your feet hurt, you are going to hate your shoes no matter how they look.)

- When getting dressed to go to a restaurant, the first step is to assess your strengths. Your focus should be on the waist up because the rest of you will be hidden under the table. What are your primary assets: cleavage, neck, arms, hair? If it’s all of these, you are one lucky lady! Otherwise, pick one or two body parts to showcase.

Follow these tips and always dress for the task at hand, wherever you may find yourself in the world.

— V —

Suzanne Pollak, a mentor and lecturer in the fields of home, hearth, and hospitality, is the founder and dean of the Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits. She is the coauthor of Entertaining for Dummies, The Pat Conroy Cookbook, and The Charleston Academy of Domestic Pursuits: A Handbook of Etiquette with Recipes. Born into a diplomatic family, Pollak was raised in Africa, where her parents hosted multiple parties every week. Her South Carolina homes have been featured in the Wall Street Journal “Mansion” section and Town & Country magazine. Visit CharlestonAcademy.com or contact her at Suzanne@CharlestonAcademy.com to learn more.

Share This Story!

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST STORIES FROM VIE